I'm Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum on the news of the day — then “my take.”

Are you new here? Get free emails to your inbox daily. Would you rather listen? You can find our podcast here.

Today’s read: 15 minutes.

Our recent video.

As the Trump administration pursues its immigration agenda, many federal agents from different law enforcement agencies have been reassigned to help with new initiatives. How many agents does this apply to, and how much time are they spending focusing on immigration? Tangle’s Associate Producer Aidan Gorman explored these questions in a recent video.

Quick hits.

- The Federal Aviation Administration lifted a flight restriction at El Paso International Airport in Texas hours after it said it would ground all flights to and from the airport for 10 days, citing “special security reasons.” The Trump administration said the initial restriction came in response to “Mexican cartel drones” that breached U.S. airspace and were then disabled by the U.S. military. (The closure)

- A shooter at a school in British Columbia, Canada, killed seven people and injured 25, and two others were found dead in what authorities believe was a related incident in a nearby home. Police said the suspect died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. (The shooting)

- The Labor Department reported a 130,000 increase in nonfarm payrolls in January, and the unemployment rate fell slightly to 4.3%. The report also revised down the number of jobs added in 2025 from 584,000 to 181,000. (The numbers)

- The Trump administration reportedly plans to repeal a 2009 Environmental Protection Agency finding that highlighted six greenhouse gases as a threat to public health and welfare. The finding served as the legal basis for federal greenhouse-gas regulation, and the agency’s new rule will remove requirements to measure, report, certify, and comply with federal emission standards for several industries. (The report)

- Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA) revealed the names of six men that he said were “likely incriminated” by the government’s investigation into convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein but whose names were redacted from recently released files. Khanna called on the Justice Department to explain the redactions. (The update)

You've cut the lattes, skipped Target runs, and said no to avocado toast.

But somehow your monthly bills are still eating your paycheck alive. Here's the thing: you're probably overpaying for most of them.

Car insurance companies bank on you not shopping around (people save up to $1,025/year when they do). Amazon counts on you clicking "buy now" without checking if it's cheaper elsewhere.

Credit card companies love those high interest rates you're stuck with. The Penny Hoarder compiled 5 of the best ways to slash your biggest bills without giving up anything — from stopping Amazon overpayments to getting chunks of debt forgiven.

See the top 5 ways to cut your bills.

Today’s topic.

The decreasing murder rate. In January 2026, the Council on Criminal Justice (CCJ) released a report finding that murders and violent crimes in the United States decreased significantly in 2025. According to the report, the murder rate in 35 large U.S. cities fell 21% last year — the biggest one-year drop ever — to what could be its lowest level since 1900. Furthermore, 11 of 13 types of violent crime tracked by CCJ all decreased in 2025; drug crimes increased by 7% while the rate of sexual crimes remained unchanged.

A closer look: The CCJ annual report examines yearly and monthly rates of 13 violent, property, and drug offenses reported to police in 40 large cities that reported monthly data consistently over the past eight years. In total, reported aggravated assaults decreased by 9%, gun assaults by 22%, domestic violence by 2%, robbery by 23%, and carjacking (a type of robbery) by 43%. Not all cities reported data for every crime listed, and the data is subject to revision, so CCJ notes that the data should be interpreted with caution. In particular, the national homicide rate will be reported with more accuracy later this year when the FBI releases data for all jurisdictions; CCJ expects that final number to reach 4 homicides per 100,000 people.

Although the change between 2024 and 2025 is dramatic, crime data also fell across most measures between 2019 and 2025, including a steep decline since the spike in crime during the first two years of the Covid-19 pandemic. In particular, homicides have decreased by 25% since 2019, while residential burglary dropped by over 40%. Aggravated assault decreased at a lower rate while nonresidential burglary increased by 1% and car thefts increased by 9%.

The Trump administration celebrated the drop in crime, with several officials crediting their policies for the dramatic decrease. “President Trump swiftly delivered by vocally being tough on crime, unequivocally backing law enforcement, and standing firm on violent criminals being held to the fullest extent of the law,” White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said.

Many policy analysts suggested that the declining rates were continuations of a trend that had been disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic. “When COVID hit, and the world shut down, we basically turned off the water with respect to prevention and intervention strategies,” Alexis Piquero, the director of the Bureau of Justice Statistics under President Joe Biden, said.

We’ll cover what the left and right are saying about the decreasing violent crime and homicide numbers below. Then, Senior Editor Will Kaback gives his take.

What the left is saying.

- Many on the left are skeptical that immigration enforcement is reducing crime.

- Some argue that broader post-pandemic social trends are responsible.

- Others suggest that innovative programs in Democratic cities are contributing to the drop.

The New York Times editorial board said “crime keeps falling. Here’s why.”

“America’s leaders typically rush to move on from a crisis once it is over, but we want to pause on the recent surge of violent crime and its reversal. We see two central lessons from this period that can help policymakers reduce crime even further,” the board wrote. “The first lesson is the importance of public trust and stability…. During the pandemic, reckless driving, deaths from car crashes and road rage incidents increased. Alcohol and drug deaths also rose. Even little things, like people using phones in movie theaters, seemed to worsen even after Covid receded. It was as if many Americans took a so-called moral holiday.”

“The second lesson involves the importance of law enforcement,” the board said. “Virtually all sides in the debate made mistakes during this intense period. Among the most damaging was the growing belief among Democratic officials that enforcing the law could be counterproductive when it involved low-level offenses such as public drug use, shoplifting and homeless encampments… The situation has partly reversed in the past few years. The defund movement is considered a failure, and many of its old backers have distanced themselves from it… With crime falling, however, there is a risk that public officials will once again become complacent.”

In Bloomberg, Justin Fox asked “are video games and phones helping to reduce crime?”

“There seems to be a reasonably clear line from the social disruptions caused by the pandemic and the outrage and protests in response to George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis police officer in May 2020 to the subsequent rise in violent crime, and the fading effects of those events probably explain much of the drop. They don’t really explain the size of last year’s decline, though,” Fox wrote. “What does? President Donald Trump’s deportation campaign was the biggest development in US law enforcement in 2025, and it’s plausible that it is reducing reported crime although not necessarily for the reasons you might think. An even more important development, though, may be that the young men disproportionately responsible for crime are now too preoccupied with their phones and other electronic devices to bother.”

“The steepest rate of decline in the RTCI data is for murder,” Fox said. “The CCJ solicited expert opinions on what its chief executive officer, Adam Gelb, called ‘a historic collapse in the homicide rate’ and received a range of answers, several focusing on crime-prevention programs that got a boost in funding during the Biden administration. A couple of respondents hinted at what one called ‘larger social movements’ at work, and in a call last month, Gelb and CCJ researcher Ernesto Lopez pointed to one in particular: the decline in social activity among teenagers and young adults.”

In MS NOW, Cleveland, Ohio, Mayor Justin Bibb (D) argued “the crime rate is falling in spite of Trump — and because of Democratic mayors like me.”

“This week, the Trump administration tried to take credit for crime dropping in cities across the country,” Bibb wrote. “The DHS is right that in city after city led by Democratic mayors, violent crime is dropping, with some cities even hitting historic lows. But it is egregiously misleading and brazenly hypocritical of the White House to try to take credit. The truth is that it’s all happening in spite of Donald Trump, not because of him. Instead of working to reduce crime, Trump and Republicans in Washington have pushed unprecedented cuts to critical government and community-based public safety programs our cities rely on.”

“But Democratic mayors have stepped up to demonstrate what real leadership looks like, to continue to move our cities forward. We are managing what we can control and doubling down on programs and strategies that work — the majority of which were designed by and for the communities we serve. And as a result of this leadership, across the country, Democratic-led cities are seeing major reductions in violent crime and homicides,” Bibb said. “We’ve seen the same trend in my hometown of Cleveland. Our Raising Investment in Safety for Everyone Initiative has helped contribute to significant reductions in violent crime across the city, with homicides declining by 26%.”

What the right is saying.

- The right is mixed on the causes of the murder rate drop, with some attributing it mostly to gradual social change.

- Some argue that Trump’s immigration enforcement efforts are the biggest factor.

- Others caution against repeating 2020-era policies that caused the murder spike.

The National Review editors celebrated “the historically low murder rate.”

“Commenting on his institution’s report, the CEO of the Council on Criminal Justice suggested that ‘it’s extremely difficult to disentangle and pinpoint what’s actually driving the drop.’ Perhaps so. Irrespective, this latest reduction is part of a salutary trend that began in the mid-1990s and, with the exception of the Covid-era spike, has continued unbroken ever since,” the editors wrote. “Relative to today, the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s were remarkably violent, with the murder rate swinging between eight and ten per 100,000 residents. In 2025, that rate was four per 100,000 residents — an extraordinary improvement.”

“There are likely many causes of this change. Since the 1960s, we have become progressively better at policing trouble zones — an effort that has been aided by improved technology and the use of statistical tools such as CompStat. Since the 1980s, the incarceration rate has risen sharply, taking more repeat offenders off the streets. Over time, the United States has grown older and less active,” the editors said. “Simultaneously, America has grown richer, and, in most periods, unemployment has been low. Locks and alarms have improved, while surveillance has become more common. And lead paint and leaded gasoline, which some studies suggest caused impulsivity and aggression in those who were exposed to them in childhood, have all but disappeared from the market.”

In Fox News, Brett L. Tolman and Ja’Ron K. Smith said “Trump’s immigration policies are working.”

“This data shows the power of real deterrence, the effect of giving law enforcement respect and support to do their job. The fact that these historic drops occurred in the absence of passing new laws gives strong evidence to the power of simply letting law enforcement do their jobs,” Tolman and Smith wrote. “Conservative Americans have always known that lawlessness — whether from violent repeat offenders or criminal illegal aliens — makes our cities less safe. Under Trump’s unwavering leadership, the pendulum is finally swinging back toward sanity. He is proving what we’ve long known: you can’t have public safety without border security.”

“Anyone who wants to call this immigration enforcement ‘overreach’ should ask the families in Chicago, Los Angeles or Miami who no longer fear nightly gunfire and mayhem. Ask the parents whose kids are no longer walking past open-air drug markets on their way to school. Americans don’t care about D.C. talking points. They care about the results,” Tolman and Smith said. “The CCJ report notes that today’s violent crime levels are even lower than they were in 2019 — before the pandemic and the defund-the-police chaos. While liberals spent the last five years demonizing law enforcement, Trump stood with the men and women in uniform. Now we’re seeing the payoff.”

In The Free Press, Charles Fain Lehman wrote “the murder rate is plummeting. You’ll never guess why.”

“Deliberately or not, accounts of the tumbling murder rate are ignoring the elephant in the room: Murder spiked in 2020 because of anti-cop protests, which drove down police activity, and it’s declined since, because big-city leaders started using the criminal justice system again. It’s really that simple,” Lehman said. “Five years ago, the murder of George Floyd instigated one of the largest protest movements in American history. Local, state, and federal leaders either endorsed ‘defund the police’ or, more often, acknowledged its advocates had some good points. Concurrently, police activity and staffing fell in big cities (where most of the crime is), as demoralized cops left the force… Unsurprisingly, murder soared.”

“It seems like the murder drop is happening because cops are doing more with less. In particular, they seem to have focused on bringing murder down, while sidelining other, less significant crimes. This helps explain surging public disorder, which has remained high even as homicide has dropped. But disorder can spiral into more serious crime. Putting off dealing with it now may cause big problems down the road,” Lehman wrote. “Whether or not it does depends, in large part, on whether we choose to repeat the mistakes we made in 2020. The surge in crime raised the appetite for enforcement. But as crime stats tick down, it’s likely that criticisms of the criminal justice system — merited or otherwise — will once again gain public attention.”

My take.

Reminder: “My take” is a section where we give ourselves space to share a personal opinion. If you have feedback, criticism or compliments, don't unsubscribe. Write in by replying to this email, or leave a comment.

- The declining murder rate is good news but hard to explain.

- Federally funded crime prevention strategies and increased policing are likely factors but probably not the only ones.

- We need more data to understand the root causes.

Senior Editor Will Kaback: A genuinely positive national story is so rare these days that we should appreciate the magnitude of the falling murder rate before discussing its causes.

The topline takeaway is understandably dominating the headlines: In 2025, homicides in the United States are projected to have decreased to a 126-year low of 4.0 per 100,000 residents. But that’s hardly all the good news. 11 of 13 categories of major crimes fell in 2025 — nine of them by 10% or more. Overall rates of violent crime decreased to below pre-pandemic levels. Perhaps most promising, these declines didn’t come out of nowhere; they continue a multi-year trend.

Now the question is why.

The pandemic-era surge in violent crime looms large over this debate, but at this point, Covid lockdowns, social disruptions to navigate the pandemic, and racial justice/anti-police protests are firmly in the past. As seen in the commentary above, disparate explanations abound: Biden-era community intervention programs, Trump-era immigration crackdowns, post-Covid social changes, improved trauma care, fewer shootings, lower unemployment, resurgent police forces and even increased social media use are just a few of the plausible, intermingling hypotheses for why crime — and murder specifically — has been decreasing. Of course, prior to the pandemic, crime in the U.S. had been steadily decreasing for decades, so our present situation may be a continuation of a larger trend, too. The only statement on this issue I feel confident making with absolute certainty is that you shouldn’t listen to anyone proclaiming the drop is due to any single cause.

That idea extends to most issues involving crime. As a public policy major in college, I remember presenting my senior thesis adviser with a regression analysis that I thought made an airtight case for a causal relationship between bail reforms and a decrease in crime. He looked over my paper, took a beat, then listed off about 20 variables I hadn’t considered that could reasonably explain (in part) the drop in crime rates I was studying. His advice followed naturally: Crime is a big, messy issue, and we’re a big, messy country. As much as we pine for simple explanations that confirm our priors, gaining any real insight from this topic requires humility and an open mind.

It was — and is — great guidance, and I’ll carry it forward today. I’m not going to bog down the take with a linear regression (that’s probably best for everyone involved), but I think we can isolate some key factors that have and have not changed since the rate began to fall. Correlation doesn’t equal causation, but it can help light the path.

First, the variables that haven’t shifted significantly and are probably less relevant: The gun ownership rate has not changed with the murder rate, the poverty rate has plateaued or slightly increased (depending on the metric), and the incarceration rate has ticked up following a pandemic dip but remains below pre-Covid levels.

Other trends are more complicated. The rates of reported murders and violent crimes cleared by police have correlated with the violent crime rate, but as crime policy expert Jeff Asher noted in October, this isn’t straightforward. Discrepancies between which jurisdictions report their figures and when could be complicating the picture, and higher murder clearance rates could be a result — rather than a cause — of less crime. Also, this nationwide trend is a composite of many city-wide trends that are all driven by different dynamics. Some cities have implemented more progressive policing approaches while others have returned to tough-on-crime policing tactics. All of these factors offer potential explanations worthy of examination. However, based on current information, I don’t think they’re key causes.

What factors are more likely to be causal? Let’s start with federal government initiatives. The Democrat-led 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) authorized $1.9 trillion in Covid-relief spending, and $362 billion of that money went to financially stabilizing local governments. Some of these resources were dog-eared specifically for crime prevention — state and local governments invested $10 billion of those funds in public-safety initiatives. One example was Atlanta’s street outreach program to connect community mediators with people identified as high risk for committing violence. Another was Indianapolis’s Violent Crime Reduction Grant Program, which funds organizations offering counseling and employment opportunities to people in dangerous situations.

Recent studies have shown compelling links between these localized efforts and lower crime rates, and the quantity of funds deployed by the ARPA for these programs is one of the few initiatives from the past six years that matches up with the national scale of the violent crime decline. Overall, the ARPA threw a lot of money at a lot of areas, and while the overall allocation has been reasonably maligned for jumpstarting inflation, it also helped state and local governments reassert their roles in critical functions like policing and public services.

More recently, some on the right have said that President Trump’s mass deportation effort has driven down violent crime rates. Brett L. Tolman and Ja’Ron K. Smith (under “What the right is saying”) noted the crime drop has coincided with an increase in immigration arrests. However, this correlation is one year old and may not be causal, and Tolman and Smith offered no empirical support to show those deported were responsible for crime rates in prior years. In my view, two things are likely true at once: Trump is deporting some violent offenders who had illegally entered the country, and the number of those deportations cannot explain the sharp nationwide decline or pre-existing trend.

An alternate explanation espoused by many conservatives — that the decline is due to the return of tough-on-crime policies — is much more persuasive. As policy researcher Charles Fain Lehman wrote (under “What the right is saying”) in June, voters in big, Democratic cities have begun rejecting leaders who embraced police and criminal justice reform in the summer of 2020 in favor of more outspoken pro-police politicians who emphasize public safety. In turn, police have been empowered to pursue preventative crime-fighting measures. The evidence for this theory is less robust than it is for strategies like community intervention, but it is more than plausible. One analysis (from a pro-police organization) found a close relationship between police activity and the murder rate in major U.S. cities since 2018; other studies have shown that aggressive policing in “hot spot” areas where violent crime is concentrated brings down crime. Lastly, overall police staffing levels in many cities remain below pre-pandemic levels, suggesting that police strategy is more relevant than the number of staff. These dynamics need further study, but the shift towards more policing is likely another causal factor in declining crime rates.

Politicians and commentators tend to talk about these policies like they are mutually exclusive — that if one works, the other doesn’t — when in reality, the drop in murders is likely the cumulative result of many different efforts. Federal funding, policing tactics, changes in elected leaders, and community interventions all matter — and, yes, even large-scale deportations could play a role.

Holding all of these ideas at once is challenging. Some might think of this issue as a jigsaw puzzle, others as a math problem. I look at it like a stew. Some components are immediately visible, like our post-pandemic return to normalcy. Other parts you have to taste to detect — community-based violence prevention programs, increased police activity, and heightened immigration enforcement. And some more complex stews have mystery ingredients — discernible but hard to place — that require deeper consideration.

Since I began thinking about the decreasing murder rate, one potential mystery ingredient has lurked in the back of my mind: screens. Young people — a demographic responsible for a disproportionate share of violent crime — now spend far more time socializing and entertaining themselves online rather than in public spaces. One fundamental principle of criminology suggests that when daily routines change, crime opportunities change with them. Fewer in-person gatherings could mean fewer disputes that escalate into violence or opportunities for lower level criminality.

This isn’t to say screen use totally neutralizes aggressive behavior, and this hypothesis must reckon with the 2020–21 homicide spike that occurred during a historic period of online activity. But people are much less likely (or able) to physically respond to an insult when it’s delivered online and not in person.

Zooming out, we have an incredible opportunity before us: a chance to not only maintain lower violent crime rates but also understand them and carry those lessons forward. Taking advantage of that opportunity requires a willingness to consider all potential factors and to accept that the answers might involve findings that don’t fit neatly into political narratives about crime.

Take the survey: What do you think is causing the decrease in violent crime and homicides? Let us know.

Disagree? That's okay. Our opinion is just one of many. Write in and let us know why, and we'll consider publishing your feedback.

Your questions, answered.

Q: Why do the issues surrounding trans athletes seem to be all focused on their participation in women’s sports? Are there issues of trans men wanting to participate in men’s sports but being restricted?

— Nicole from Puyallup, WA

Tangle: Great, and fair, question. Restrictions on trans men’s participation in men’s sports are a little more complicated, with more relaxed rules at the collegiate level but varying rules at the state level. As of February 2025, the NCAA’s official policy allows student-athletes of any natal sex to participate competitively on men’s teams; on women’s teams, student-athletes assigned male at birth are allowed to practice but not to compete. The policy is complicated by hormone therapy, as testosterone — a naturally occurring chemical used in gender-affirming and other hormone therapies — can also be used as a performance-enhancing drug. As such, the NCAA requires trans student-athletes undergoing therapy with testosterone to comply with its medical exception standards.

However, some trans men have been restricted from competing at different levels. For example, Mack Beggs, a trans man wrestling in Texas, competed in the girls’ division in high school due to state laws, even winning the girls’ championship. In college, Beggs wrestled on the men’s team under the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics. Additionally, in the 2026 Winter Olympics, a trans man named Elis Lundholm competed on the Swedish women’s ski team.

Want to have a question answered in the newsletter? You can reply to this email (it goes straight to our inbox) or fill out this form.

Under the radar.

On Monday, President Donald Trump posted on Truth Social that he would block the opening of the Gordie Howe Bridge — a new crossing over the Detroit River linking Michigan and Ontario — until the United States is “fully compensated” by Canada. The bridge is co-owned by the U.S. and Canada, although construction was entirely funded by Canada and is nearly complete. An agreement reached between the two nations over a decade ago stated that Canada would collect toll revenue from crossings until it recoups the bridge’s $4.7 billion construction cost, but Trump is now threatening to block the bridge unless the tolls are split 50–50 with the U.S. Trump’s threat followed a meeting between Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick and Matthew Moroun, whose family owns and operates the nearby Ambassador Bridge. Bloomberg has the story.

Your monthly bills are robbing you blind.

Car insurance, Amazon purchases, credit cards — companies are counting on you not noticing the overcharges.

People are saving $1,025/year on insurance alone, plus stopping debt interest and Amazon overpayments.

See the top 5 ways regular people are cutting bills without giving up anything.

Numbers.

- 10.4. The homicide rate per 100,000 residents in 35 cities for which homicide data was available at the end of 2025, according to the Council on Criminal Justice (CCJ).

- 18.6. The homicide rate per 100,000 residents in 2021, the highest rate in the past eight years.

- –21%. The percent change in the reported homicide rate between 2024 and 2025.

- –44%. The percent change in the rate between 2021 and 2025.

- –41%. The percent change in the homicide rate from 2024 to 2025 in Denver, Colorado, the largest change among the reporting cities.

- 35. The number of cities that reported their homicide data to the CCJ.

The extras.

- One year ago today we wrote about trans women in women’s sports.

- The most clicked link in yesterday’s newsletter was the ad in the free version listing 16 Amazon hacks.

- Nothing to do with politics: Norway’s Johannes Høsflot Klæbo’s outrageous uphill skiing technique.

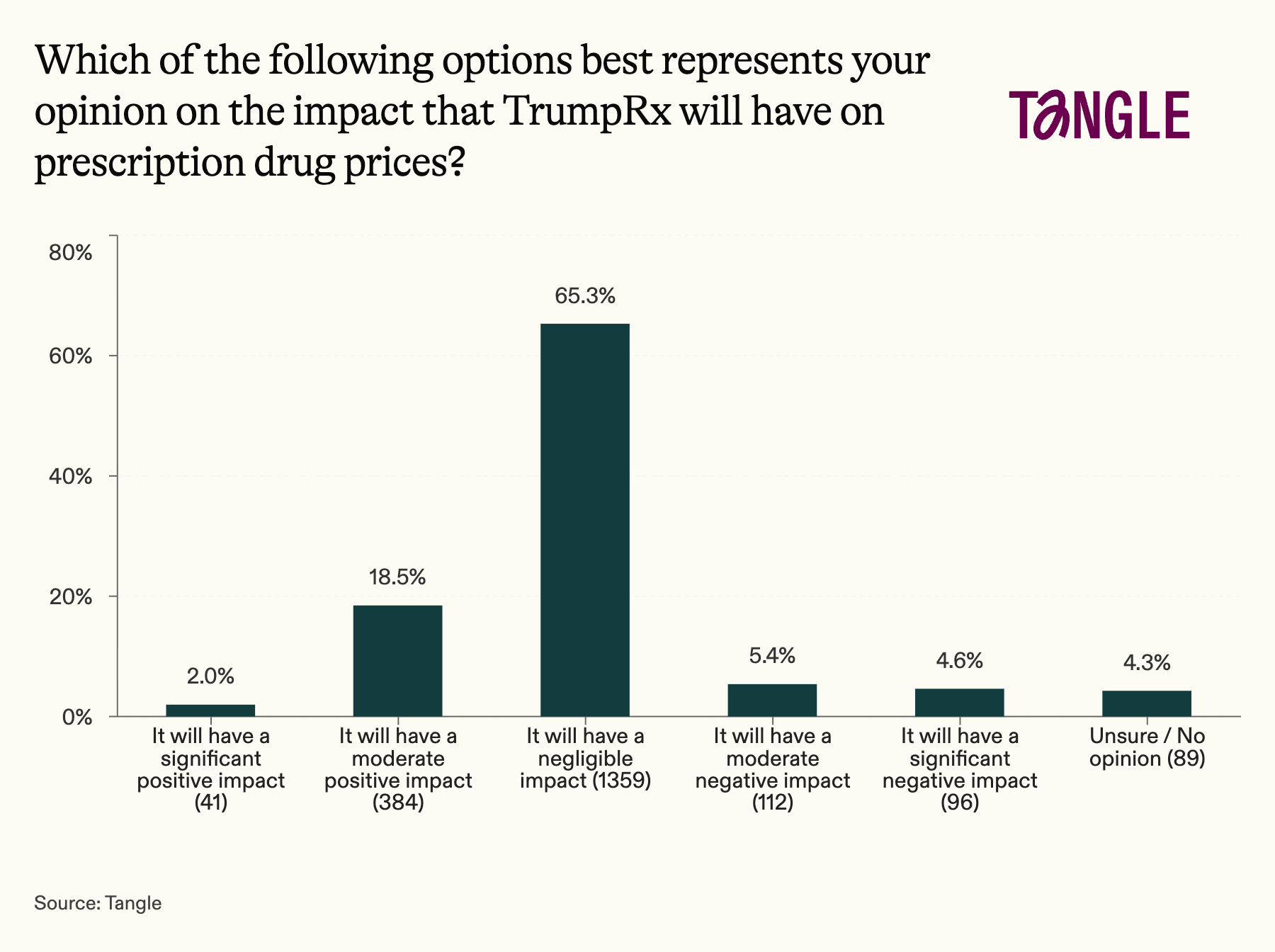

- Yesterday’s survey: 2,081 readers responded to our survey on TrumpRx with 65% saying the new program will have a negligible impact. “These are not lifesaving medicines,” one respondent said. “It’s a start (and better than nothing),” said another.

Have a nice day.

Daniel and Ginger Poleschook live on Loon Lake in Washington state, where they’ve been part of wildlife rescues during the winter months. One rescue in January stands apart: a deer had wandered onto the lake and appeared too far off the shore for the couple to rescue her safely. They called for help, and firefighter Gavyn Gallagher walked out onto the thin ice in a technical suit designed to protect him if he went through the ice. He eventually reached the deer and managed to tie a rope around her, then hugged the animal as they were pulled to shore. The deer was released after being checked for injury and hypothermia. “She ran off as, as expected, to do deer things,” Grant Samsill, a Department of Fish and Wildlife official, said. The Washington Post has the story — and video.

Member comments