Answering your questions.

Over the last couple of months, our inbox has been inundated with questions about the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

Readers from across the political spectrum are trying to separate fact from fiction: Can ICE actually arrest U.S. citizens? What are my rights when a Border Patrol officer talks to me? How are all of these agents being trained amid a massive hiring push by the Trump administration?

Online and in the opinion sections of news outlets, misinformation has been rampant. In our own coverage, we’ve tried to address some of these questions, but the answers are often legally nuanced and impossible to sum up in a single sentence, a post on X, or a thirty-second TikTok video.

Today, though, we’re going to address them in detail.

In order to get to the bottom of these questions, we spoke with a wide array of experts: Andrew “Art” Arthur, a former immigration judge who now works at the Center for Immigration Studies; César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, the Gregory Williams Chair in Civil Rights and Civil Liberties at The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law; attorney Sarah Isgur, who is also the co-host of Advisory Opinions and a legal analyst at The Dispatch; and Joshua Ederheimer, who spent years overseeing training policy at DHS.

Reminder: Today’s edition is for premium members. As a free reader, you’ll receive a preview of the piece, but you’ll need to subscribe to read the full thing.

Who are DHS agents?

What is the difference between ICE and CBP?

ICE and CBP are enforcement agencies within DHS; their missions have significant overlap, but their responsibilities are different. CBP is made up of three branches: Border Patrol, which you’ve seen a lot in the news. Office of Field Operations, the agents you encounter at ports of entry at border crossings or in the airport (they are the ones inspecting your bags for illegal goods). Finally, Air and Marine Operations, which — as the name implies — handle air and marine approaches to the United States.

Per federal regulation, Border Patrol has specialized enforcement authority anywhere within 100 miles of the border, but they may also be assigned to conduct inland enforcement with other DHS agencies (like Operation Metro Surge in Minneapolis). Like all federal immigration officers, Border Patrol agents can stop or detain anyone if they have reasonable suspicion (see “Terry stops” below) to believe they’re in the country illegally. Probable cause, or observations that lead agents to reasonably believe a person is unlawfully present, is generally required for them to conduct arrests or searches, though Border Patrol agents can often conduct routine searches at immigration checkpoints without it.

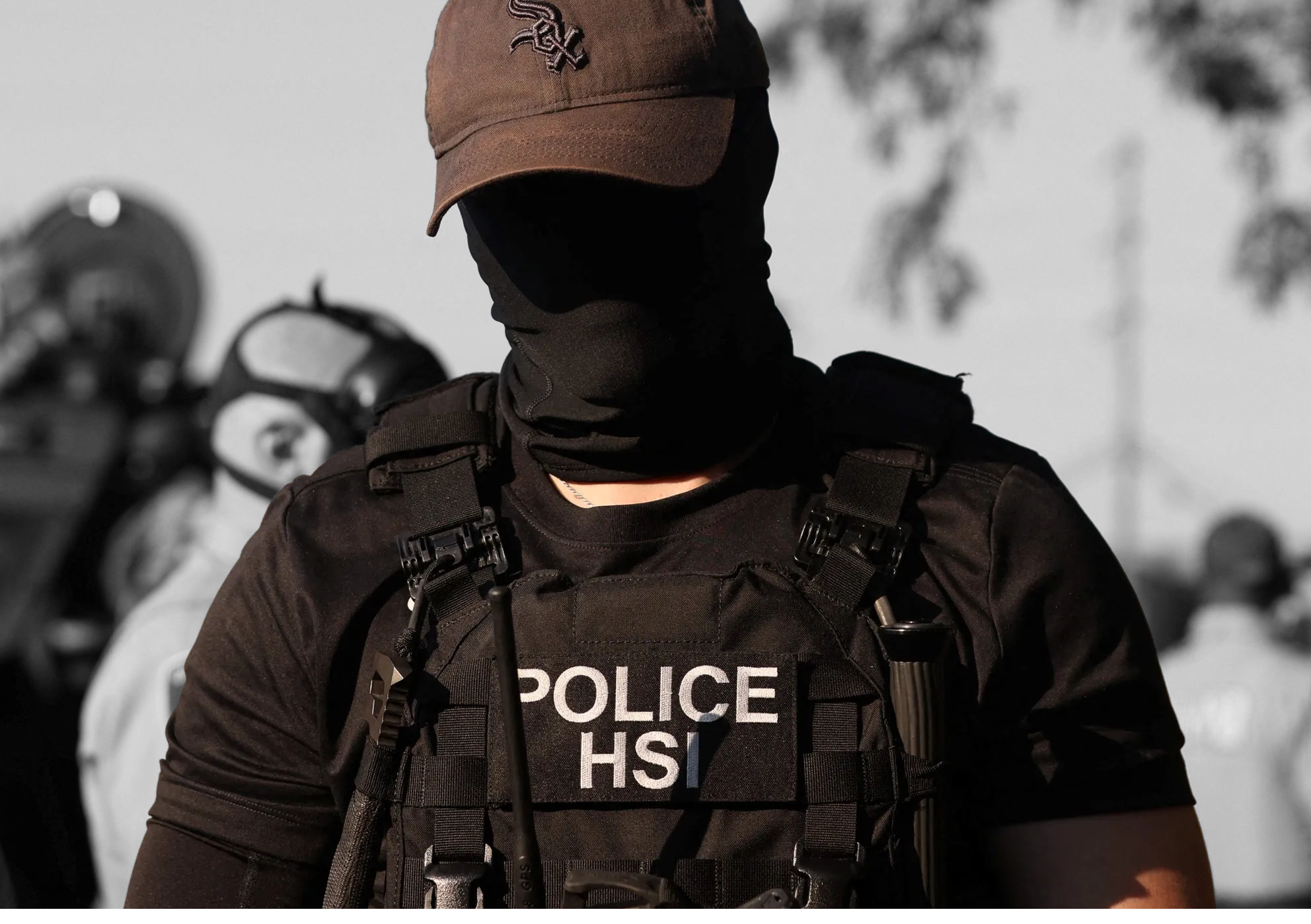

ICE, which has two branches, is primarily responsible for finding and removing people in the United States illegally. ICE’s two branches are the Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO), the agents you’ve seen on the news in places like Minneapolis, and Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) special agents. HSI is ICE’s main investigative arm; they are also present in Minnesota, but they are focused on investigating fraud.

As you can see, CBP and ICE have considerable overlap in focus and responsibility, though they differ in important and meaningful ways. And each agency has sub-divisions that specialize further. Importantly, though, their authority is the same, and their goals are usually aligned — so these divisions often work cooperatively.

Who works for these agencies? How have they been recruited or trained, and how has that changed over the past year?

ICE and CBP are primarily staffed by federal immigration officers, but they also have a wide range of support staff such as lawyers, analysts, and administrators. According to a recent press release, ICE employs 22,000 personnel; per their career FAQ page, this includes more than 8,500 in both ERO and HSI, including over 6,500 special agents in the latter. Notably, other pages on ICE’s website have differing numbers. For example, the HSI webpage lists its employment at over 10,000 employees with 6,000 special agents, and the ICE careers homepage says HSI has 10,400 employees with 7,100 special agents.

Over the last year, ICE has grown significantly, increasing its number of officers and agents from 10,000 to over 22,000, according to a January press release. Part of this hiring boom has come from an increased budget, allowing ICE to offer incentives like up to $50,000 signing bonuses and student loan repayment and forgiveness. It has also broadened its hiring pool, with Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem eliminating the age requirement and cap to work for ICE in August. Previously, applicants had to be between the ages of 21 and 37 or 40, depending on the position they were applying for. Now, applicants can be as young as 18, and there is no upper limit on age.

In our interview, Joshua Ederheimer, the former DHS training leader, noted a few possible concerns with this hiring push. Ederheimer worried that the number of instructors and supervisors had not kept pace with the number of new recruits, and he questioned how these individuals have been trained. Noting Noem’s decision to drop the age requirement, he also said that he would ensure that the screening process included evaluations of maturity levels and judgment.

Federal officers mostly undergo the same basic training program on constitutional rights, search and seizure, firearms, and traffic stops. After that, they participate in training specifically tailored to the mission of their organization. For example, ICE may focus on fugitive apprehension and transportation of subjects in custody, while CBP may train recruits on enforcement near the border and the use of certain monitoring technologies.

DHS officers undergo de-escalation training and are trained on the agency’s use of force policy. Many outlets have reported that DHS has cut the training requirements for ICE recruits, but the extent of the changes is unclear. Some reports put the new training duration at six or eight weeks; however, the ICE website still lists training as five weeks of Spanish language learning and 16 weeks in immigration enforcement. Senior ICE official Caleb Vitello told AP in August that ICE cut Spanish training requirements to reduce training time by five weeks, opting instead to use increased translation technology services. Ederheimer also noted that the training timeline could have been shortened without cutting training hours by extending daily instruction or adding an extra day per week.

When do DHS agents have to identify themselves?

Federal law requires every immigration officer to identify themselves as an officer “who is authorized to execute an arrest,” but they are not explicitly required to give their name or other identifying information. This requirement includes the caveat that agents do not need to identify themselves until they deem it “practical and safe” to do so.

For ICE specifically, agents can refer to themselves as “federal officers” or “police” when approaching a suspect, but once an arrest is initiated, they must identify themselves as an “immigration officer” (again, with the “practical and safe” caveat).

These regulations are typical for law enforcement as a whole. In fact, DHS rules on identification may be stricter in some cases. The U.S. does not have a federal law universally requiring law enforcement officers to identify themselves or display their name/badge in every public interaction, though local laws or department-specific policies require it in some places.

What are agents doing?

I thought being here illegally or overstaying a visa was a civil offense or misdemeanor, not a serious crime. Why can ICE or Border Patrol arrest people when they aren’t actually committing criminal offenses?

It’s true that “unlawful presence” alone is a civil offense, not a criminal offense; it’s also true that illegal status is often what DHS agents are looking for when they detain someone, and DHS is perfectly within its authority to detain and remove someone simply for entering the country illegally. Further, conduct related to “unlawful presence,” like eluding inspection, is a criminal misdemeanor on the first offense and a felony on the second offense, and the two often go hand in hand.

Similarly, overstaying a visa is also not a crime. However, people who overstay visas are often committing separate crimes. For example: Anyone who is here on a visa is required to notify DHS within 10 days of a change of address; failure to do so is a criminal misdemeanor. Those who stay in the country and work here without a visa may be committing crimes like document fraud or identity theft to obtain employment.

Put succinctly: Unlawful presence alone is a civil offense, but staying here unlawfully usually entails other misdemeanors or felonies.

Can ICE detain U.S. citizens? When can these arrests take place and when can’t they?