I'm Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum on the news of the day — then “my take.”

Are you new here? Get free emails to your inbox daily. Would you rather listen? You can find our podcast here.

Today’s read: 15 minutes.

Your Savings Account Is Quietly Losing You Money

Most of us opened our savings account years ago and never thought about it again. It's probably earning you nearly nothing—and that's exactly what traditional banks are counting on.

Here's the thing: while your money sits earning 0.4%, other savings accounts are paying 4%+ APY¹. On $50,000, that's the difference between $200 and $2,000+ in annual interest. That's real money you're leaving on the table.

Raisin connects you to high-yield savings accounts offering 4%+ APY¹, and right now they're offering up to $1,000² in bonus cash when you open an account by November 30 with code EASY.

Moving your money takes minutes. Leaving it where it is costs you every single day.

One week.

What do immigration, gerrymandering, and the 2028 presidential election have in common? They’re the main topics of our live event in Southern California, which is just over one week away. Tangle’s Isaac Saul will be moderating a spirited discussion with Kmele Foster, Alex Thompson, and Ana Kasparian on these big issues (and more). We’d love to see you there, and tickets are still available!

Quick hits.

- A federal judge temporarily blocked the Trump administration from using the ongoing government shutdown as grounds to lay off federal workers, suggesting that the administration had “taken advantage of the lapse in government spending and government functioning” to conduct the layoffs. (The ruling)

- The Trump administration has reportedly given authorization to the Central Intelligence Agency to conduct covert operations in Venezuela, allowing the agency to carry out lethal operations in the country and other operations in the Caribbean. (The report)

- Hamas said it had returned all of the remains of Israeli hostages that it could recover, claiming that it needs special equipment to recover the remaining bodies. (The latest)

- Journalists covering the Defense Department who refused to sign a new Pentagon access policy began vacating their offices after the deadline to formally acknowledge the new policy passed. (The deadline)

- Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth said the United States will “impose costs on Russia” if Russian President Vladimir Putin does not engage with efforts to end the war in Ukraine. (The comments)

Today’s topic.

Louisiana v. Callais. On Wednesday, the Supreme Court heard arguments in a case challenging the congressional map Louisiana adopted in 2022, the second time the court has considered the case. The challenge centers on Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965, which prohibits voting laws or districting practices that give members of a racial group less opportunity than others to elect candidates of their choice. During arguments, the court’s conservative justices signaled their support for narrowing or overturning Section 2.

Back up: In 2022, Louisiana’s legislature adopted a congressional map with one majority-black district of the state’s six (roughly 33% of Louisiana’s population is black). A group of black Louisiana voters challenged the map under Section 2 of the VRA, and a federal district court sided with them, ordering a new map with a second majority-black district. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit upheld the lower court’s decision.

The state legislature adopted a new map in line with the court’s ruling, but a different group of voters (describing themselves as “non-African American”) sued in 2024, alleging the map violated the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause by sorting voters based primarily on their race. A district court sided with the Callais challengers and blocked the map from going into effect, but the Supreme Court stayed that decision, allowing the map with two majority-black districts to be used in the 2024 election. The court heard arguments in its last term, but declined to issue a ruling and ordered additional arguments for this term, with a focus on “whether the State’s intentional creation of a second majority-minority congressional district violates the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.”

During the first round of arguments before the Supreme Court in March, Louisiana Solicitor General Benjamin Aguiñaga said that the state “would rather not be here” and wanted to resolve the dispute by keeping its 2024 map. The court’s conservative justices scrutinized the ruling that struck down the 2022 map and questioned whether the new map constituted an unlawful gerrymander; liberal justices suggested that the new map addressed a clear violation of the VRA’s Section 2.

On Wednesday, the court’s conservative justices explored whether the VRA’s provisions — specifically, Section 2 — should eventually expire. “This court’s cases, in a variety of contexts, have said that race-based remedies are permissible for a period of time… but that they should not be indefinite and should have an end point,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh said.

Janai Nelson, president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and attorney for the black voters who challenged the 2022 map, argued that Section 2 remained critical for preventing electoral discrimination, saying it only offers protection in extreme circumstances like the 2022 map that would have given “entrenched control” to Louisiana’s white voters. Asked by Justice Elena Kagan about the tangible impact of rolling back Section 2, Nelson replied, “The results would be pretty catastrophic.”

If the court finds Section 2 unconstitutional, states would have the option to redraw congressional and state legislative maps without considering race. Since the court typically issues major opinions in June or July, a major ruling before the end of 2025 would be uncommon. However, if the court issues its ruling on an expedited timeline, Louisiana (and other states) would be able to redraw its map before next year’s primary elections ahead of the 2026 midterms.

Today, we’ll share reactions to oral arguments from the left and right, followed by my take.

What the left is saying.

- The left expects the court to overturn Section 2 and worries that it will remove a key protection against racial gerrymandering.

- Some say the expected decision will harm black voters across the country.

- Others argue Section 2 is as vital today as it was in 1965.

In Vox, Ian Millhiser said “it sure looks like the Voting Rights Act is doomed.”

“While all six Republican justices almost certainly walked into Wednesday’s argument with a particular result in mind, they had wildly divergent theories of how to get there,” Millhiser wrote. “Justice Samuel Alito seemed to argue that maps that exclude Black voters are acceptable so long as they were enacted for the purpose of benefiting the Republican Party, rather than for explicitly white supremacist reasons. Justice Brett Kavanaugh argued that the Voting Rights Act must sunset after an undetermined amount of time. Justice Amy Coney Barrett proposed imposing a limit on Congress’s power to remedy discrimination — one that the Court has applied in nonvoting cases — on election-related laws like the VRA.

“But even if the Court’s Republican majority cannot agree on a reason why they want to kill decades-old protections against racial gerrymanders, it’s been obvious for a long time that they are eager to kill them,” Millhiser said. “The Republican justices… began the process of dismantling the Voting Rights Act a dozen years ago, in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), and they’ve handed down at least two other decisions since then that attacked this landmark civil rights law. So, in the almost certain event that Callais takes another bite out of the VRA, it will be a continuation of an ongoing Republican project.”

In Talking Points Memo, Kate Riga argued striking down Section 2 would “silence Black voters.”

“A central grievance motivating today’s conservative legal movement — and the Republican Party more broadly — holds that any measure rectifying the country’s habitual discrimination against minorities actually discriminates against the in-group,” Riga wrote. “This is why ‘black lives matter,’ a call to recognize the disproportionate violence and death Black people suffer at the hands of the state, is met with ‘all lives matter.’ It’s why DEI has become the battle cry for rolling back the perpetuation and memorializing of civil rights advancements.”

“That same grievance animated the right-wing justices Wednesday… Section 2 is the last weapon in the landmark civil rights legislation that the Roberts Court hasn’t yet destroyed, and has been a bulwark against, largely, red-state legislatures, often in the states that made up the Confederacy, using crafty line drawing to ensure that white voters always have disproportionate power over Black ones to elect the representatives of their choice,” Riga said. “It’s not an exaggeration to say that the United States was not truly a democracy before the VRA… The Supreme Court is doing its own version of that by threatening one of the last protections of our multicultural democracy.”

In The New York Times, Reps. Troy Carter and Cleo Fields (D-LA) wrote “the shadow of Jim Crow looms over the Supreme Court.”

“For over a decade, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority has been chipping away at this landmark civil rights legislation. Now the law’s Section 2, which prohibits voting practices that discriminate based on race, is at risk. If the court declares it unconstitutional, it is all but certain that one of our congressional districts will be dissolved, and quite possibly both districts,” Carter and Fields said. “Let’s be clear: Section 2 is still necessary, especially in Louisiana. Despite what some people may argue, there is no evidence to support the idea that our state’s Black voters can elect candidates of their choice without the existence of majority-Black districts.”

“When Black communities lose representation at both the state and federal levels, their concerns are often ignored or deprioritized. Black elected officials, already too few in number, are left to shoulder the burden of constituents outside their districts who feel they have nowhere else to turn. That’s not how a representative democracy is supposed to work,” Carter and Fields wrote. “The Voting Rights Act, including Section 2, has garnered bipartisan support… At the time, lawmakers across the political spectrum recognized that, left to their own devices, some states would turn back to a time when certain voices did not matter and could be disregarded. That’s just as true today as it was then.”

What the right is saying.

- The right supports rolling back Section 2, saying the court can uphold the original intent of the Voting Rights Act.

- Some say the court must address the confusing standard of race-based redistricting of its own creation.

- Others suggest the case is more about political strategy than concerns about racism.

The Wall Street Journal editorial board argued “nobody is ‘gutting’ the Voting Rights Act.”

“Headlines following oral arguments in Louisiana v. Callais on Wednesday say the Supreme Court is about to ‘gut’ the Voting Rights Act. On the contrary. Prohibiting the use of race in Congressional map-making would return the landmark civil-rights law to its original purpose: Preventing discrimination,” the board said. “Contrary to what press reports suggest, majority-minority districts are not required by Section 2. The law merely prohibits voting practices that result ‘in a denial or abridgement’ of the right to vote based on race and guarantees the right of minorities to ‘participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.’”

“A lawyer for the NAACP argued that reversing Gingles would ‘be pretty catastrophic’ since both of Louisiana’s black Members of Congress represent majority-minority districts. But as U.S. deputy solicitor general Hashim Mooppan noted, only 15 of Congress’s roughly 60 current black Members represent such districts. Black Members, like white Members, win seats more often by appealing to multiracial coalitions,” the board wrote. “The goal of Section 2 was to prevent the likes of poll taxes, not to give partisans an excuse to use race as an excuse to gerrymander or to challenge state Congressional maps in court by playing the race card.”

In National Review, Carrie Campbell Severino said the case offers an “overdue reckoning with race-based redistricting.”

The court is “confront[ing] two strains of precedent that contradict each other. On the one hand, a string of voting rights decisions starting with Thornburg v. Gingles (1986) interpreted Section Two of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) in a way that compelled states to consider race in the drawing of legislative districts,” Severino wrote. “But of course, the overarching rule that has emerged in the Court’s constitutional jurisprudence is that drawing distinctions based on race is presumptively unconstitutional and subject to strict scrutiny.”

“The inclusion of the constitutional question is a sign that a critical mass of justices is ready to grapple with the conflict in its case law. Will a majority finally fix the problem the Court left lingering in Milligan? On the one hand, the Court’s composition has not changed since that case was decided. At the same time, Justice Kavanaugh, part of the five-justice majority in Milligan, did not join Chief Justice Roberts’ opinion in its entirety,” Severino said. “Louisiana didn’t create this predicament. The Court’s confused jurisprudence did. Now the Court has an opportunity to fix it. Let’s hope a majority of the justices seize it.”

In Hot Air, John Sexton analyzed the arguments before the court.

“There’s a clear partisan angle to all of this. Black voters tend to vote for Democrats in overwhelming numbers. The result is that section 2 of the VRA effectively ensures Democrats have safe districts in a bunch of otherwise red states in the south,” Sexton said. “Just last week, Politico noted that left-leaning voting rights groups were panicking over today’s oral arguments because if section 2 gets tossed out, a bunch of safe blue districts would likely disappear. How many? Possibly as many as nineteen.”

“Where is this all going to land? I don't think it’s as clear as some previous arguments. There seem to be 3 liberals for preserving section 2, three conservatives for eliminating it and perhaps 3 conservatives (Kavanaugh, Barrett and Roberts) who may (or may not) be looking to weaken but not end it. So I think the likely outcome here is a 6-3 decision with an outraged dissent from Justice Jackson, but I’m not sure how far that decision will go,” Sexton wrote. “The [other] question is could it impact the 2026 midterms? The answer is maybe. It depends when the court issues a decision.”

My take.

Reminder: “My take” is a section where I give myself space to share my own personal opinion. If you have feedback, criticism or compliments, don't unsubscribe. Write in by replying to this email, or leave a comment.

- The origins of this case are frustratingly simple: Louisiana’s map violated the Voting Rights Act.

- The law does create some complications, but not enough for me to want the court to limit it or strike it down.

- Most frustratingly, gerrymandering will remain a scourge on our democracy either way.

Executive Editor Isaac Saul: The dynamics of this case are, for me, pull-your-hair-out levels of frustrating.

Despite both sides complicating their arguments with pedantic details, the issue at the center of the case is simple. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act is not long — you can read it here. It prohibits a political process that is not equally open to participation by members of a certain race or skin color. The 15th Amendment, which is also at play here, is all of two sentences long: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

In Louisiana, one third of the state is black. Based on a robust collection of data, we know these two relevant things about the state’s electorate: 1) black voters in the state often vote for black candidates and Democrats, and 2) white voters (even Democrats) are less likely than black voters in Louisiana to vote for black candidates (even Democratic ones).

So, Republicans who control the Louisiana state legislature, and thus its districting process, did something simple: In 2022, they “cracked and packed” areas where a lot of black Louisianans live and created a Congressional map that had one majority-minority district and five districts where whites are the majority. They got their desired result: Five districts elected Republican officials (all white) and one district elected a Democrat (who was black).

Again: None of this is complicated. Little of it is contested. Voters sued, arguing that the maps self-evidently diluted the power of black voters — or, to put in the terms of Section 2, closed the political process off to a class of people based on race by diluting their vote. They won their case, which means they proved in court that the gerrymander had the effect of violating Section 2, whether the mapmakers intended to racially gerrymander or not (intent doesn’t matter, which Congress made explicit with an amendment to the Voting Rights Act in 1982).

Still, up to this point, everything is simple: Republican mapmakers diluted black votes. In a state where the proportion of black voters would suggest at least two congressional districts would be competitive for Democrats and majority black, the state’s legislature instead produced five non-competitive Republican seats and one majority-black Democratic-held seat.

The Gingles framework the court uses to determine a Section 2 violation has three elements: 1) The minority group is large and compact enough to form a majority in an additional district. 2) The minority group is politically cohesive. 3) The majority votes as a bloc in a way that usually defeats the minority’s preferred candidate. These three elements are increasingly hard to satisfy because black Americans are less segregated (compact) now than they used to be, and because their voting preferences are less predictable (politically cohesive) than they used to be. These are good things, and for these reasons (and contrary to rhetoric from conservative justices), Section 2 cases are increasingly rare and increasingly unsuccessful — they’re only upheld when egregious racial gerrymanders satisfy all three of the above components.

That’s exactly what we have in Louisiana.

The next step is where things get a little complicated. A court told the state to redraw its map, and this time Louisiana decided to create a compliant map that still protected incumbent Republicans like House Speaker Mike Johnson. Its solution was to draw a second majority-black district into Louisiana's map. Then, a group of “non-African American” voters sued, saying the new map violated their constitutional rights by being a racial gerrymander — a kind of racial gerrymander against the racial majority.

As the liberal justices argued laboriously and convincingly (but perhaps futilely), the remedy had to consider race because the initial violation was based on race. Calling foul here is akin to someone following you around with a bullhorn that blasts music every time you try to speak, and when a court rules they violated your First Amendment rights, the bullhorn-wielding stalker claims that their free speech rights are being violated because the court is silencing them. It is an unbelievably, incredibly aggravating circular piece of litigation. But it’s where we are.

Admittedly, the way the law protects voters’ rights invites genuine complications. States are simultaneously being told that they cannot consider race while drawing maps, but also that the Voting Rights Act demands they consider race while evaluating or remedying racial gerrymandering. At the same time, when voters of a particular race overwhelmingly vote for one party over another, it can be hard to test whether a gerrymander is targeting their race (unconstitutional) or their partisanship (constitutional). This uneven framework creates problems exactly like Louisiana’s.

But that confusion doesn’t justify throwing out Section 2, which has been remarkably effective. As NAACP attorney Janai Nelson argued before the court, Section 2 enforcement has led to less racial polarization in districts and fewer cases of its kind over time (i.e. less racial gerrymandering). In other words: The statute is accomplishing the goals Congress intended it to. And although members of the court, like Justice Kavanaugh, seem to think those protections have served their purpose and should expire, the threat it protects against remains present. Indeed, we are not somehow beyond the threat of racial gerrymandering; we are amid it.

The reality of gutting or even narrowing Section 2 is that Republicans could (and will) gerrymander as many as a dozen Democratic-held seats out of existence, several of which are held by black representatives who were elected in districts where a majority of black voters reside, and probably before the 2026 midterms. The political outcome here is only relevant because it proves that gerrymandering affects fair representation — that affects all of us, but in this case it boxes black voters out of the system unfairly and unconstitutionally.

Equally perplexing and frustrating is that the conservative justices all seem to want to weaken Section 2 in some way, but they each have very different ideas for how to do that — which made the oral arguments in the case clunky and disconnected. While the liberal wing of the court spent a lot of time inquiring about the practical implications of Section 2, Louisiana’s Solicitor General Benjamin Aguiñaga spent a lot of time arguing unlikely hypotheticals to make it seem as if the downstream effects of narrowing Section 2 would be no big deal.

For example, Aguiñaga was pressed on the idea that weakening Section 2 would have a catastrophic impact for black voters in Louisiana. In response, he argued that the Republican legislature would hesitate to draw a 6–0 map in the wake of any such ruling, because the hundreds of thousands of Democratic voters have to “go somewhere,” and Republicans would risk drawing “purple” districts into existence.

But overreaching actually isn’t much of a risk for Republicans in Louisiana. Aided by complex algorithms and advanced gerrymandering strategies, they won’t have any trouble drawing a 6–0 map — an elections analyst from The New York Times did it pretty easily. And you can bet your house Republicans are going to try.

Similarly frustrating are the mental gymnastics I’m observing from conservatives about how this litigation is playing out. National Review’s editors, for whom I have great respect, published an editorial headlined “End Racial Gerrymandering.” One might expect the editors to call on Republicans to stop cracking and packing black voters into single districts across the south, but instead they demand the Supreme Court solve racial gerrymandering by ignoring the problem. The editors write:

Section 2 never even mentions the drawing of district lines. It asks instead whether a state’s “political processes leading to nomination or election . . . are not equally open to participation” by members of racial groups who “have less opportunity than other members of the electorate to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.” … In reality, every state’s political system today is equally open, even if the outcomes of elections are often a disappointment to voters outside of the partisan majority.

Actually, an election is not equally open to voters if elected officials of one party are drawing district lines that explicitly and obviously cram voters of a particular race into a single district. I simply don’t understand how someone can claim otherwise. This is, of course, a critique that applies to gerrymandering writ large; but legally, it carries the most weight when applied to racial gerrymandering, which is the issue before the court today.

I’m not sure what’s going to happen now. Most courtwatchers are confident that the court will issue a 6–3 decision weakening Section 2 in some way. I’m hesitant to make a prediction that runs counter to the observations of the court-obsessed pundits, but I do think a 5–4 ruling preserving Section 2 is possible, with Kavanaugh and Roberts joining the liberal wing. I genuinely just have a hard time believing that the weight of the precedent here (which was affirmed by this court as recently as 2023), paired with the truly circular nature of Louisiana’s argument, creates a decision that reverses Section 2, especially when the conservative justices are so divided about how to move forward.

Whatever the outcome, it remains true that gerrymandering is a scourge on our democracy, and it’s getting worse by the day. I would obviously prefer Congress to ban gerrymandering of all kinds, but that can’t happen today. And as a strident advocate for voting, it brings me no pleasure to say this: In a world where legislators can so easily pick their voters, even along obvious racial lines, it becomes hard to defend the value of participating in our system at all. The Supreme Court’s pollyannish view on what will happen if they leave mapmakers to their own devices leaves me deeply uneasy about our future, and my sincere hope is that they surprise us the same way they did the last time a case like this was before them. But I’m not optimistic.

Take the survey: How do you think the court will, or should, rule on this case? Let us know.

Disagree? That's okay. My opinion is just one of many. Write in and let us know why, and we'll consider publishing your feedback.

Your Cash Deserves Better

Traditional banks pay almost nothing on savings accounts—and they're counting on you being too busy to care. Meanwhile, other FDIC-member banks are offering 4%+ APY on the exact same money.

Raisin connects you to 75+ high-yield options in minutes. Open by November 30 with code EASY and get up to $1,000² in bonus cash.

Your money should work as hard as you do.

Your questions, answered.

We're skipping the reader question today to give our main story some extra space. Want to have a question answered in the newsletter? You can reply to this email (it goes straight to our inbox) or fill out this form.

Under the radar.

On Monday, Cuban dissident José Daniel Ferrer left Cuba for the United States at the request of the U.S. government. Ferrer was one of 75 opposition figures tried and imprisoned in 2003 for leading movements against Cuba’s communist government. He continued his protest activity and was imprisoned again in 2021; human rights organizations like Amnesty International have designated him as a “prisoner of conscience.” Earlier this month, Ferrer’s family circulated a letter saying he would accept exile from his home country. Secretary of State Marco Rubio confirmed Ferrer’s arrival in the U.S., saying he endured “years of abuse, torture, and threats to his life in Cuba.” The Associated Press has the story.

Numbers.

- 60. The approximate number of years since the Voting Rights Act (VRA) was passed.

- 466. The number of VRA Section 2 cases that have resulted in published decisions or opinions since 1982, according to an analysis by the University of Michigan’s Voting Rights Initiative.

- 73%. The percentage of those cases that addressed claims of vote dilution.

- 43%. The percentage of Section 2 cases in which the plaintiff achieved successful outcomes (defined here).

- 45 and 71. The number of successful and unsuccessful Section 2 cases, respectively, brought between 2012 and 2024.

- 71%. The percentage of Section 2 cases in which at least one black plaintiff participated.

- 27%. The percentage of Section 2 cases in which at least one Latino plaintiff participated.

- 2%. The percentage of Section 2 cases in which at least one white plaintiff participated.

The extras.

- One year ago today we wrote about Kamala Harris’s agenda for black men.

- The most clicked link in yesterday’s newsletter was the 80 most iconic guitar intros of all time.

- Nothing to do with politics: This year’s winners of the Pure Street Photography awards.

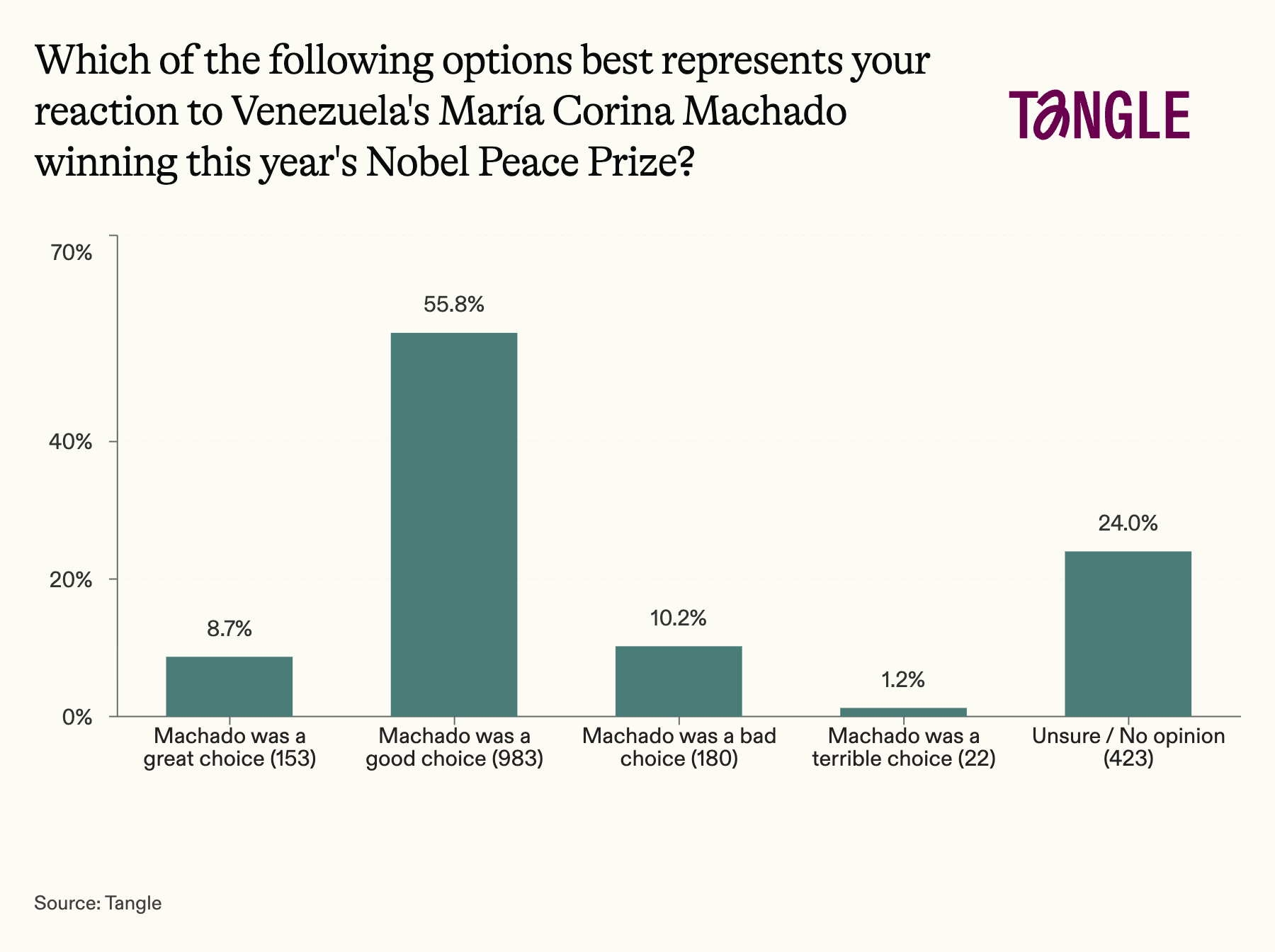

- Yesterday’s survey: 1,761 readers responded to our survey on the Nobel Peace Prize with 65% favoring the choice of María Corina Machado. “Machado was a ‘questionable’ choice,” one respondent said. “I am Venezuelan, I am against Maduro; nevertheless I believe that [the Nobel decision] prompts actions and decisions that do not contribute to the end goal,” said another.

Have a nice day.

Plagued with guilt over his decision to turn his brother Ted Kaczynski (the “Unabomber”) in to authorities in 1996, David Kaczynski decided to reach out to some victims of his brother’s attacks. Gary Wright had been left severely injured when a bomb placed by Ted exploded outside Wright’s computer store in Salt Lake City in 1987, and he was one of the few people who responded to David. The two have struck up an unlikely friendship over the years, making joint appearances and communicating regularly. “I think Gary has been one of the greatest blessings of my life,” David said. “It shows that friendship across differences and barriers is really possible.” CBS News has the story.

¹ APY means Annual Percentage Yield. APY is accurate as of October 15, 2025. Interest rate and APY may change after initial deposit depending on the terms of the specific product selected. Minimum opening deposit is $1.00.

² New customers only. Earn a cash bonus when you deposit and maintain funds with partner banks on the Raisin platform. Customers will receive $75 for depositing between $10,000 and $24,499, $250 for depositing between $25,000 and $49,999, $500 for depositing between $50,000 and $99,999, and $1,000 for depositing $100,000 or more. To qualify for the bonus, your first deposit must be initiated between August 1, 2025, and November 30, 2025, by 11:59 PM ET, and the promo code EASY must be entered at the time of sign-up. Only funds deposited within 14 days of the initial deposit date and maintained with partner banks on the Raisin platform for 90 days will be eligible for this bonus. Bonus cash will be deposited by Raisin into the customer’s linked external bank account within 30 days of meeting all qualifying terms. This offer is available to new customers only and may not be combined with any other bonus offers. Raisin may modify or end this offer at any time and may withhold or revoke bonuses in cases of fraud, abuse, or violation of these terms or Raisin’s Terms of Service.

Member comments