A little something different.

I'm Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle. By popular demand, today's post is a members-only piece on my trip to Bolivia. Be sure to check out our note at the end.

Our first wreck happened in the first couple hours of the first day, which in some ways was a relief.

All morning we had been peppering our guide Chris with questions about the trip. What was the most dangerous? What was the most exciting? What do we do at police checkpoints? What mistakes do most people make? How scary is "Death Road," really?

For each question he had a story — almost all of them about how a certain group he had over the last decade of touring Bolivia on motorcycles had screwed up in some memorable way. The Belgians who crashed on this turn or the Colorado couple who got stuck in a day of rain on the mountain or the Israeli who couldn't decide whether to stay on the bike or ride in the support truck or the Russians who were just uncontrollably rambunctious and wild. Each story had some new fun tale of adventure and danger tied to a specific group that had been burned into Chris's memory, most of them involving some kind of accident or near-accident.

Finally, my cousin Marco asked the question I, for one, was also wondering: "I'm starting to feel like I want to hear a story about a trip where nobody ever dropped the bike. Does that ever happen?" Marco said with a nervous laugh.

Chris thought for a moment.

A few seconds passed.

"There was this band of brothers a few trips ago who all stayed up the whole trip," he said.

Another pause.

"But they had been touring the world on motorcycles and were pretty experienced."

Marco was the first to go down.

Our trip started in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, a "big, hot, humid, crowded city" as my cousin Lico described it to me before I arrived. This was a trip of cousins. My cousin Marco, a naturopathic doctor treating neurological issues from Seattle who had years of experience riding a street bike in Hawaii. My cousin Lico, who grew up between Mexico and Texas and New Mexico and has spent his entire life riding and driving and fixing anything with a motor. His wife, Linda, an outfitter who runs horse stables across the Southwest but would spend this trip as Lico's passenger. My cousin Willy, Linda's son, exactly my age, a white water river guide living in New Mexico. And me, the writer from Philadelphia who had never ridden more than 20 miles in a day and had never driven anything bigger than a 250cc dirt bike.

Thanks to my late Granny's insistence on all of us traveling with each other, my cousins and I all essentially grew up together and have remained extremely close into adulthood. This was neither the first nor the last time we'd go to some far away place together but it was, so far, probably the craziest thing we'd done as a group.

Santa Cruz was, in fact, crowded and hot and humid, and also combustible. The city is Bolivia's largest, with an estimated 3 million people, and it sits east of the easternmost portion of the Andes Mountains (which are visible on a clear day). It's built on a series of densely populated rings and perpendicular roads that run through the rings as you get into the city. If you're ever lost, Chris told me, you simply find a ring you know then ride in a circle until you get back to a familiar spot.

And there’s plenty of tension in Santa Cruz. A few weeks before I landed at the Santa Cruz airport, the right-wing governor of Santa Cruz — Luis Camacho — had arrived at the very same airport only to be apprehended by police and promptly thrown in jail. He was charged with terrorism for a "coup" in 2019 against socialist leader Evo Morales. Camacho's arrest sparked weeks of protests by his supporters — protests that would pop up during our trip and are still going on now (along with protests from supporters of Morales who want him back on the presidential ballot). In Bolivia, they call these protests bloqueos, or blockades, and they are an effective way for Bolivians to express their displeasure with the current government. Often, days- or weeks-long bloqueos — where entire towns or roads get shut down — will end with the resignation or removal of certain politicians or policies.

Unfortunately, Camacho's story is not unique. Bolivia is widely considered one of the most corrupt countries in South America, and a long line of leaders have suffered the same fate he did. In the last few years alone, Evo Morales was forced out of office in 2019 after protests against his administration spread across the country, ultimately leading to the police mutinying and the military urging him to step down. He was replaced by Jeanine Añez's interim right-wing government, which promptly charged Morales for sedition and terrorism and issued an arrest warrant for him, then detained the top officials from his administration.

Morales was never imprisoned (he fled to Mexico), but in 2020, the current President Luis Arce was elected. His victory brought Morales's party back to power, and they returned the favor by prosecuting Añez on terrorism charges. She was held in pretrial detention for more than a year, and then sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2022. She remains in jail today.

Now Arce's administration has arrested Camacho, citing his support for protests against Morales, and promptly tossed him in jail, too. Santa Cruz residents have mostly moved on from any hope of freeing Añez, but they continue to protest against Camacho's detention in hopes that he doesn't suffer the same fate.

And here I was, thinking the 2024 U.S. election was getting messy.

My plans had already gone sideways thanks to an illness that kept me from a friend's wedding in Mexico and a Frontier Airlines screw-up that made me miss my first flight to Bolivia. I was supposed to be coming from Mexico to Bolivia a day earlier, but instead was flying from Philly through Miami to Santa Cruz. By the time we arrived at Chris's house to load up on the bikes, I had been in transit for almost 24 hours and was coming off five or six hours of sleep on a red-eye flight. There wasn't much time to relax or worry.

At Chris's house, the bikes were all parked neatly in his backyard and ready to rock. I should mention, as a point of interest, that when I say "Chris's house" the language I’m using is a little deceptive. He'd explain later on our trip that he lived in the house via a program called "anticrético" — which as far as I can tell is unique to Bolivia. The idea is pretty simple and also — to my American ear — complete lunacy.

Here's how it works: Chris gives a large chunk of money (it has to be cash) to the owner of the house, who is contractually obligated to pay him that money back in full at the end of two years. In the meantime, Chris gets to live in the house rent-free. The homeowner is supposed to use or invest the money in a smart way that makes it easy for him to pay Chris back in two years, which gets Chris out of his house and also helps (presumably) the home owner make profit on the cash he was lent by making a good investment. If the home owner can't pay the money back, he has to either find another person to lend him an amount equal to or more than what Chris did so he can pay Chris back, or Chris gets his house.

That's anticrético.

For the motorcycle enthusiasts, of which I learned there were many among the Tangle readership when I announced this trip, the bikes were 650cc dual sport Kawasaki KLRs. They were beasts. Capable, nimble, powerful, able to ride on any surface and in any condition, and — as we'd learn shortly — any altitude. Chris had also customized them in various ways to meet the needs of the trip, including adding gigantic 7 to 8 gallon gas tanks which added about 40 pounds of fuel (I was reminded that gasoline weighs less than water) to the 450 pound bikes.

There wasn't much time to think about what we were doing between gearing up and leaving Chris's house. We met our second guide, Federico, who would drive a support pick-up truck behind us during the trip. The truck held our luggage and an additional functioning motorcycle to swap in or use for parts in case one of the ones we were riding broke down. We packed up the truck, got on the bikes, fired them up, and pulled out of the driveway.

From our brief orientation that morning, a few important rules had stuck in my mind: 1) Chris leads. Don't pass Chris. 2) Always keep an eye on the person behind you. If you can't see them, pull over, so the person in front of you pulls over, so eventually Chris pulls over, and we all make sure we stick together. 3) When we're off-road, ride far enough behind the person in front of you that the dust settles before you get to them, otherwise the motors will eat so much dust they'll start having trouble as the trip goes on. 4) Never show a Bolivian police officer more documentation than they ask for, and pretend you don't speak Spanish even if you do (Lico and Willy, who grew up on the border, are both fluent. Marco, Linda, and I are all passable but had no trouble playing the role of clueless gringos). 5) You're in Bolivia. Things are not going to go to plan. Be patient.

On our first spate of riding I was second in line behind Chris and he threw us into the deep end with little hesitation. We immediately hit a two-lane highway where he was passing cars and semis in oncoming traffic lanes at speeds between 50 and 65 miles per hour. Though I had hours and hours of off-road experience under my belt, I had only ridden a motorcycle at that speed a couple times in my life — something I decided not to mention. Instead I went into city driver mode and faithfully followed Chris into the abyss, bobbing and weaving through the hairy Bolivian traffic and taking all the same lines he did. Cars beeped and pulled up next to us and semi trucks blew their horns and people rolled down their windows and stared and we carried on, a line of motorcycles cutting through traffic like a marble finding its way down a pinball machine. It took about 90 seconds for me to start having the time of my life. Say what you will about their danger — and yes, they are quite dangerous — motorcycles are unbelievably fun. Especially big, badass, fast, powerful motorcycles like these.

Despite our agility and aggression, when we got to our first stop, I turned around to see Federico in the support truck right behind us — a feat my brain had a hard time computing and one that would stun me over and over for the rest of the trip, leaving me to determine he was one of the most capable people I'd ever met. Chris broke out a bag of coca leaves and we all exchanged some “When in Rome” glances before stuffing wads into our mouths. Any buzz was non-existent, at least for me, but the leaves, mixed with a little baking soda to activate them, did a good job keeping us alert and fighting off the altitude sickness. They became a regular occurrence after lunch on the trip, and each time we all laughed to ourselves at the absurdity of it.

Day 1 was a test, and we passed — but barely. After our first run through traffic Chris took us across a hanging bridge where we had a couple of inches on each side of our handlebars to get through. The bridge was made of wooden slats and chains and fresh on my mind was the story Chris had told that morning about the person on his last trip who spilled on the bridge and got tangled in the chains and caused a huge mess.

We all got through unscathed. After the bridge we got to the dirt, sand and gravel, and I immediately found myself grateful for the motocross boots I had bought for the trip. This was my comfort zone: Kicking up dust and rocks and using the foot break and taking sharp gravel-y turns and getting my feet down to save myself from spills and standing up for big bumps or crouching down to dodge branches and doing it all at around 15 or 20 miles per hour, where falling would hurt but wouldn't be that bad unless you really screwed up.

A few minutes after the hanging bridge, we came around a long switchback bend on the dirt road that broke left and then hard and up to the right. It required you to break and downshift at first and then open it up to get up the hill. Willy, who proved himself a better rider than me throughout the trip, had by now passed into second place. We came around a few more bends before I realized there was nobody in my rearview mirror.

I pulled over and Willy pulled over and Chris pulled over and we all shared our last data points on when we had seen anybody behind us. We agreed it had been a while. We sat for another few minutes before Chris fired his bike back up and started off in the direction we had just come — he made it about five yards before Marco, Lico, and Linda came slowly around the corner, in what I can only describe as the motorcycle equivalent of a limp.

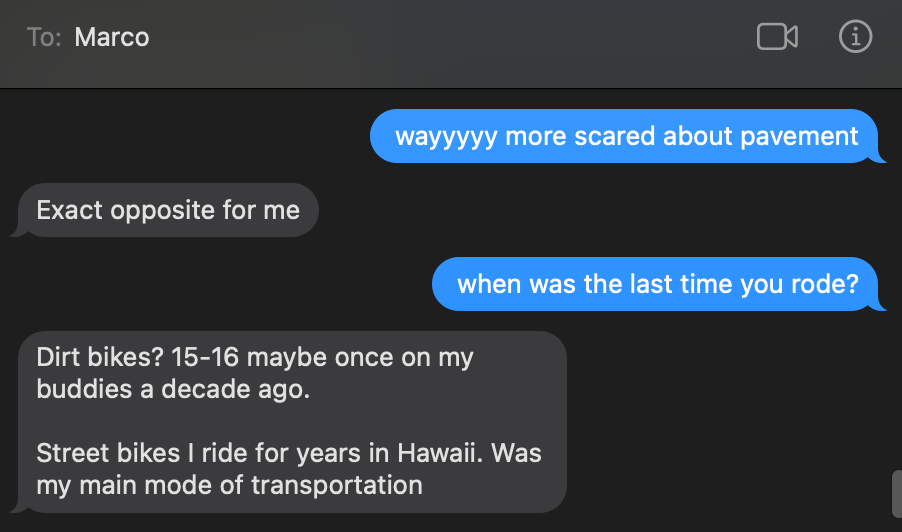

Marco had taken a fall on one of the first big bends, which he figured he took too fast. We'd find out later that day he had been using his front brake — a normal thing to do on a street bike but a cardinal sin on a dirt bike. The effect of hitting your front brake hard on dirt, in a turn, is locking up your front wheel and all but guaranteeing you're going to turn the bike over. A text conversation Marco and I had the day before suddenly became prescient:

Marco was fine. A few scrapes and a little shaken up, but the bike was a little bit of a mess. The fall had stripped the bolt on his crash bars, and Chris needed to replace it with something that wasn't so big it'd rub against the chain of his bike. Lico, who is like a moth to flame any time a car hood or toolbox opens, almost seemed excited at the opportunity to fix something. He, Chris, and Federico huddled around the bike and did about an hour of work while the rest of us sat in the shade and Marco did a little sulking. It was a bummer, and the loss of about an hour cut a waterfall hike short, but we all insisted honestly that it was no big deal and the adventure was really just beginning. This was part of the fun.

By the end of the day, everyone but Lico and Chris had dropped their bikes, too. That’s sort of the reality of riding: It’s not if but when, and more importantly how. I dropped mine while at a complete stop, on a decline, looking back over my shoulder for the person who was supposed to be behind me. This was the theme of the trip for me: On three separate occasions I dropped my bike while parking, the only times I fell on the whole trip. It got so bad that before we ascended Death Road a few days later, Chris joked to me not to worry — "you don't have to park when we get up there."

Each of my spills happened by just leaning a little too far to one side and then feeling the full weight of the bike tipping farther and farther. There is always this brief moment of panic where every muscle in your body from head to toe is activated and trying to keep the bike up, but at some point you have to decide whether you want to drop a 450-pound bike on your leg or not — and if you choose "no," it means letting the bike go and skipping off to the side and out of the way. I felt a little better on the third day of the trip when I watched Linda unexpectedly adjust herself in her seat behind Lico, sending both of them careening over to the side while at a full standstill — the kind of mistake that Lico rarely gets caught making but made me feel a little less inferior (and was quite amusing to watch happen in what seemed like slow motion).

Willy spilled on the sand and managed to get back onto his bike and get it running before Chris noticed and before I pulled up behind him on the trail. He then opted not to tell anyone about it, figuring he could get away without the point against him being scored. At the next stop for food Chris took a three-second look at his bike, and like someone examining a neatly organized office where one entire wall was suddenly missing, he calmly asked Willy what happened. We’d learn quickly that Chris knew these bikes better than most of us knew ourselves, and there was really no point in keeping anything from him along the way.

Even with the falls, in a lot of ways the first day was perfect, because we got a taste of almost everything we'd experience on the rest of the trip. We touched nearly every surface there was, including some pretty exciting stream crossings. Some were rocky, which meant you had to go slow enough that you didn't catch your front wheel on a giant rock and go flying over the handlebars into the water, but fast enough to get up and over the bigger rocks that you could hardly see beneath the surface. Some stream crossings were over deep wet sand, which meant you couldn't go too slow, otherwise your back wheel would sink in and you'd get stuck. Some stream crossings were cement and man-made, covered with algae, which meant they were like ice — and braking or revving the engine as you crossed was a good way to slide out.

By far the most difficult surface for me was the wet clay, which somehow felt worse than ice, and Lico joked that it required two people to get out of if you fell (it's so slippery that one person would be hopeless keeping their footing while trying to lift a 450 pound bike off the ground). Sand, for me, was the second most difficult, because it's not obvious where it's deep or shallow and it's easy to run into dry sand expecting it to act like solid dirt only for the ground beneath you to suddenly collapse and fall apart. Mud was third, sloppy and challenging for all the reasons mud is, but also predictable and familiar. An honorable mention goes to grooved, unfinished pavement, which made it feel like you had zero control of the bike and was one of my least favorite surfaces to ride on, but in reality was probably not as dangerous as it felt.

Just before dark, we'd done some climbing and gotten to the small, sleepy mountain town of Samaipata, at about 6,000 feet of altitude. One of the things that I enjoyed the most about Bolivia was the set of names for its many gorgeous cities and tucked-away towns across the countryside that we encountered. The names are so superior to what we have here in the United States that I'll just list a few I heard in my six days there so you can hear and feel the lyricism of them all: Samaipata and Camarata and Cochabamba and Quime and Irupana and Licoma and Chulumani and Coripata and Arapata and Potosi and Sucre and Coroico and Yolosa…

At dinner that night we all piled into a small restaurant in the city center. Anytime I travel outside the U.S. I am reminded of why our colonial ancestors called the Americas the New World, and how much older the histories of so many other places are. This particular town was new in relative terms but still founded in 1618, long before the U.S., by Pedro de Escalante y Mendoza. Hundreds of years before that it had been conquered by the Inca. In the restaurant, I ordered something called the pique macho, which Chris joked was basically a collection of random things the restaurant had as leftovers. A few minutes later a gigantic plate of steak, french fries, hot dog, cheese, and some assorted vegetables appeared in front of me. It was bizarre and delicious and even for a guy well-recognized for his gluttony I had a hard time finishing it.

By the time our meal was done and day 1 was complete, I was thoroughly exhausted and excited for what was to come. Willy and I took a walk around Samaipata after dinner, stopping in at four or five cafes and asking when they opened in hopes of finding an early morning coffee. The first place told us 8am, and then each place we asked got successively later and later until we were in a bundle of laughs, gave up, and turned in for the night.

The next day was a complete whirlwind. We woke up to some sad news. Federico, our faithful guide, had found out that his son — a motor cab driver — had gotten into a motorcycle accident after hitting a dog and suffered serious injuries. He'd broken his collarbone and ribs and was headed for surgery. The dangers of motorcycles were once again staring us squarely in the face, but more urgent was the question of whether Federico's son would get surgery from a public or private hospital. The latter would be a massive financial blow, while the former would be relatively easy and much cheaper.

We sat around and discussed the options for a little while before Chris snapped us back to attention, got us to breakfast, got us on the bikes, and got us moving. We had to cover 240 miles in a single day traveling from Samaipata to Cochabamba — a feat that quickly became one of the most difficult physical and mental challenges I'd ever taken on. By the end of the day my hands were so tired I couldn't unbutton my pants or open a bag of chips. For eight hours, we ascended and descended mountains, tore through switchbacks, and touched almost every climate that exists on the planet: Tropical jungles, dry desert, fertile grasslands, and mountain cold — all in one day. It was remarkable.

About halfway through Chris warned us about the "cloud forest," a famous portion of our trip where we would pass through a microclimate in the mountains. Chris's advice was vague but direct: If the weather gets bad, just keep riding, and I promise it'll change in 15 minutes.

Let's just say it was obvious when we hit the cloud forest.

Chris and Marco were each 40 or 50 yards in front of me on the road as we climbed the mountain switchbacks on pavement and I had them both in my sights. Suddenly, though, we found ourselves surrounded on all sides by a dense fog that quickly turned to thick rain clouds. It felt like some supervillain X-Men character was about to appear out of the darkness. Chris and Marco disappeared, literally, right in front of my eyes — fading off into nothingness. Then the rain started in earnest.

The visor on my helmet wasn't beading the raindrops nicely so I flipped it up, only to realize my sunglasses were fogged up and covered in rain, too. For the next few minutes I fidgeted with both, and ultimately landed on pulling my sunglasses down the bridge of my nose and leaving my visor up so I could see in front of me, even at the cost of sacrificing my face to the elements. I'm not exaggerating when I say my visibility was about 10 feet. I slowed to a crawl, maybe 7 or 8 miles per hour. I looked in every direction for Chris and Marco but couldn't find them. I kept hearing Chris's last piece of advice: Just keep going, it'll end in about 15 minutes.

15 minutes later I still felt like I was trapped inside a funhouse mirror of rain clouds. I started to question if maybe Marco and Chris had pulled over and in my limited visibility I didn't notice. My heart rate went up. Did I make a wrong turn? Am I going in circles? Am I sure riding through this is the right call? Suddenly a pair of headlights appeared 10 feet ahead of me and a van buzzed by, missing me by about three feet to my left. I realized I was riding down the center of the road. I was just about to call it quits when a bright blob of sun appeared in the thick clouds above my head. I rode another 20 feet and the road was suddenly dry, the thick rain clouds I had been driving inside of suddenly turned back to fog, and a minute later I was standing on the side of the road with Marco staring at this:

The cloud forest was behind us and we were back in the hot, sunny tropical mountains, if such a thing exists. Lico, Linda and Willy appeared shortly after, and shared their tale of getting stuck behind a truck full of pigs for the entirety of the cloud forest — enjoying the spray of mud and feces as they putted along blindly through the rain.

I started to get a lot more comfortable on the pavement as the day went on. Unlike in a car, where you often take the inside edge of a turn and allow your momentum to pull you out toward the center lane, a motorcycle is almost the opposite: As a turn approaches, you want to move yourself toward the center lane and then cut across the inside of the turn as it flattens out. I spent the first few hours of the day watching how Chris, Marco, Willy and Lico were riding, and then started mimicking their lines. I found myself chatting and singing out loud as I rode along, falling into a mantra I'd carry for the rest of the trip: Trust the bike, ride the wave. I started to lean in and feel the bike's balance and take the curves a little bit faster and more competently as I got a feel for the rhythm of the road.

As the afternoon hours of the day wore on I became exhausted, but also motivated. A couple hours were left on the clock before I could celebrate proudly with a beer that I had conquered 240 miles in a single day. I'd fallen second in line behind Chris on some of the switchbacks and for the first time was actually keeping pace with him — either he had slowed down or I was getting better, probably a little bit of both.

While we were descending from one of our big climbs we made a series of sharp left and right rolling turns through the switchbacks. On one of the steepest and sharpest, I peeked in my rearview mirror after I accelerated out of the turn and saw — about 15 yards behind me — someone in our group take the turn at an angle that didn't look possible. The bike and person aboard it looked about eight inches off the ground, leaning fully to the left with their knees almost grazing the pavement. And then they never appeared around the bend.

After about a hundred yards I broke into something near a panic and double backed. There was no sign of whoever it was behind me — Willy or Marco — and I had about a 30-second ride back up the switchback hills to the spot where I last saw them. I was totally unsure what I would be coming onto. As I turned the last bend a couple of cars passed me, which I took as a good sign — I figured if someone had a really serious crash or was injured badly the traffic would have stopped. Then, there on the side of the road, I saw Marco standing without his helmet on, looking slightly shocked, his bike a few yards off the embankment and into the woods.

He wasn't entirely sure what had happened and neither was I, which made the whole thing even more unsettling. He'd been cruising easily on the pavement since we'd left the dirt. But something went wrong on this turn. The bike was remarkably unscathed, but Marco was legitimately hurt. His leg was bruised and swollen from the knee down to the ankle and would only worsen over the next few days.

Given that Marco was the doctor in the family, we mostly left him to his own devices to figure out how to take care of himself. After a few minutes talking about what had happened, he dusted himself off and hopped back on the bike to finish the day’s ride. It was a fit of bravery or stupidity or more likely some of each, but either way I respected it and wondered if I’d be able to do the same. While we all went out to a steak dinner in Cochabamba that night (I ordered a gigantic Tomahawk-sized steak that cost about $11 USD), Marco hung back, iced his leg, and ordered dinner at the steakhouse off a picture of the menu I sent him. Again, he was understandably shaken up. And again, he demonstrated quite a bit of chutzpah — hopping right back on the bike the next morning, leg wrapped and attitude mended.

As it turned out, Willy was the first of us to tap out and ride in the support truck for a break. He and his mom Linda spent the day trailing behind us as we began the big climb to La Paz, one of Bolivia's capital cities, the highest administrative capital in the world — it sits at 12,000 feet above sea level.

That day's ride was by far the most dramatic and stunning of the first three days, and maybe the whole trip. We'd do another 200-plus miles, but this time we went through the Andes mountains and the altiplano, or the high plains, climbing out of the mountains and then onto flat land at elevation and then back into the mountain switchbacks.

The peculiarities of Bolivia started to show themselves: There were stray dogs in the mountains at 14,000 feet who'd sprint out in front of your motorcycle or nip at your heels, while others would sit quietly and stare meaningfully at you as you passed. It’s hard to say which was more unsettling. You'd see indigenous folks walking along the side of the road, impossibly isolated and far from any town or village, their presence at that altitude and their ability to walk up those steep hills nearly inconceivable. There were kids on the side of the highway in dresses waving flags that were a signal to pull over so they could perform before asking you for money, and kids dressed down waving plastic bags who were asking for food.

When we pulled through some old dusty villages, it felt as if the entire town would stop and stare at the gringos on their fancy loud motorcycles. In other towns, it felt like we were invisible, and people would hardly look up. Adobe houses abound, with a mix of ruins and new structures and fertile farms as far as the eye could see.

At one point, a group of teenage boys walking along the side of a four-lane highway saw us coming around the bend and all threw their arms into the air, clapping and cheering for us as we passed, as if recognizing we were on a marathon of a ride. We began seeing llamas and alpacas on the side of the road, too, many like this, which became one the great joys of the trip:

Shortly after seeing my first one, Willy pulled up in the support truck with a plastic bag of barbecue llama he had just bought on the side of the road. I have a rule about eating things, and it's that I'll pretty much eat anything. Especially if I can watch someone else eat it first, especially if I've never tried it before, and especially if it's meat. I felt guilty, having just fallen for the cute llamas myself, but I'm an enthusiastic carnivore and my curiosity won the day. It was delicious — tender like pork and simple like chicken, seasoned to perfection (I'll spare you the details, but let's just say that about 12 hours later the llama had the last laugh).

At one point on our trip, Chris told us that the landscape of Bolivia would be hard to put into words to people back home and the pictures would never do it justice. He was right but I'll still try, on both accounts.

Imagine for a moment the view when you’re in a plane and your flight’s landing, when you're sitting in the window seat and looking down at the tops of clouds and about to push through them. There's always this great majestic beauty to it — this long floor of puffy white globs below you, knowing that the whole world is hidden on the other side, bracing for the brief moment of turbulence as you pass through them and whatever city you are landing in is exposed on the other side. I almost always see someone on the plane snapping photos at that moment.

Now take those clouds and imagine them being pierced sporadically as far as you can see with gigantic mountains covered in bright green eucalyptus trees. Now imagine a few of those mountains piercing the clouds have waterfalls running down the sides of them. Now imagine above the clouds, around the mountains, great giant birds of prey like condors are circling. Drop in some goats and wild white horses and llamas and alpacas on the green countryside underneath the eucalyptus trees. Add a little bit of a nice gentle rain. Make it sunset. Now, on the bluffs of the animal-covered mountain sides with eucalyptus trees and bursting waterfalls, create a few kelly green lawns in your mind, and then scatter upon them ancient stone structures.

Hold all of that for a moment, as you stare out the airplane window. Now remove the glass of the window. Now remove the plane. Actually, just the roof, window and floor are gone, but you're still sitting in your airplane seat, with an entire 360-degree panoramic view of everything around you, holding onto two rumbling handlebars, the gentle rain on your exposed wrists and the clouds literally in your breath and the entire landscape and animals and spray of the waterfalls on your face.

That's what it's like to pull through the Andes on a motorcycle. And Chris is right, the words and photos don't do it justice.

Many of the indigenous people in these scattered villages have a very specific look, especially the women. They're often carrying a satchel bag of sorts wrapped around their upper bodies and stuffed with their belongings or some kind of crop. Peculiarly, many are also wearing tiny bowler hats, the product of a remarkable story from the 19th century of two brothers who had shipped the hats to Bolivia from England. When the hats arrived, the brothers discovered they were too small to fit the heads of the British men working in Bolivia they had intended to sell them to. In an act of business savvy, they pivoted, deciding to sell them to the local population under the guise that these tiny hats were some kind of fad in England — a must-have among European women. The story managed to stick, as did the style. This is the modern-day result:

The final two days of my trip were the biggest riding days of the whole journey. It started with 110 miles of nothing but off-roading on more switchback mountains — but this time, with traffic. Chris had warned us this would be the most grueling day, and Marco's leg was getting bad enough for him to finally decide to get some rest — tagging Willy back in from the support truck. The trip didn’t go as planned from the beginning, and we ran into every conceivable issue Bolivia has to offer.

At gas stations throughout the country, you have to present your identification and registration in order to fuel up. Many Bolivians don't have their vehicles registered, which means they have to wait in long lines for the unregistered vehicles to get a gallon or two of gas into a can. Chris had registered all of our bikes, but sometimes the more official line was long, too, and sometimes the gas stations were simply bone dry. This was the case on the second half of our trip. Interestingly, I’d learned that in certain places close to the border, the Bolivian gas — which is much cheaper than it is in some surrounding countries — is mixed with a dye. This way, people can't smuggle fuel across the border and re-sell it at a profit.

We ran into a traffic jam caused by a giant line for a gas station that had effectively shut an entire road down. Then we ran into a traffic jam caused by two semi trucks coming nose-to-nose on a "two-lane" road where the pass was so narrow and perilously close to a cliff on the bend that they couldn't pass each other, requiring one truck to go all the way back up a mountain side in reverse and all of us to hold our bikes off to the side on the cliff (bizarrely, as one of the semis sat in the middle of the road, I noticed it was adorned with some incredible American iconography).

On two separate occasions road closures from traffic jams or construction rerouted us on our journey, and in both instances a local in the town offered to lead us on our detour. One happily took a tip for the help and the other strenuously rejected until Chris stuffed a few bolivianos (or "B's" as he called them) into the dashboard of his motorcycle and then took off. As a group, we helped push a broken down van uphill and out of the way, and then I watched the driver start the car by rolling it in reverse back down the hill and firing up the engine (it was the first time I'd ever seen someone push start a car in reverse).

Sometimes, as you exited a small town, there'd be a person sitting in a lawn chair in front of a chain tied up to two posts blocking the road. A few had official, government-looking jackets, and others just looked like normal people. Either way, we'd stop, chat, pay the toll or talk our way out of it, and carry on. Motorcycles don't have to pay tolls on the highways, which saved us a lot of time and some money on our journey.

I saw some things I loved in Bolivia — the kind of stuff that made me go "huh, why don't we do that?" Like a small town where the garbage man rings a bell on his truck as he drives around, like an ice cream truck, alerting everyone he’s coming so they can put their trash out to the curb before he gets there. My cousin Willy also remarked to me at one point that so many Latin American countries had things he wished we still had in the U.S., like simple shops with leather workers who can repair something like a shoe. Willy’s dog had just chewed off the tiny little loop on the heel of his boot that you use to pull it onto your foot, and he made the astute point that in the U.S. he basically had to return the boot or buy a new one — but in every single town we had stopped in on our trip there was a little leather shop where he could have gotten it fixed.

There was also some stuff I was very glad we don't have, like the way some Bolivian cities set up their electric wires:

There were images, too, that'll always be burned into my brain from the trip: The man sitting inconspicuously in a wheelchair in the middle of nowhere at about 12,000 feet altitude on a dusty dirt road, who simply looked up and offered us a wave and a toothless smile as we passed him. The indigenous cholitas on the side of the road scrolling through their iPhones. The sea of eucalyptus and coca leaves that flanked us for so much of the trip. Our hotel manager, on our fourth night, using a giant extendable pole with a knife on the end to harvest fresh mangoes off of a tree behind our rooms before bringing them to us during dinner. Turning a corner on the road and seeing the orange speck of Chris’s helmet up and to the right in some seemingly impossible position on the side of a mountain, and then realizing he was a few hundred yards ahead on the road I was about to traverse. The long pigtail braids nearly every woman seemed to wear her hair in, each tied off at the end with some kind of decorative tchotchke.

There were also things that were uniquely Bolivian, but reminded me that people everywhere tend to act similarly. There is a divide among the Collas and Cambas in Bolivia. Cambas typically refers to people in the eastern, tropical part of Bolivia, the area around Santa Cruz, while Collas are the population from Western Bolivia. Cambas are much more associated with the indigenous culture and look, and Collas and Cambas have a longstanding cultural and political divide. You might hear someone degrade a politician because they are a Camba or even use the word Colla as an expletive. Learning about it reminded me of my regular talking point — a sad irony of our world — that the people who fight the most are always the most similar. The Israelis and Palestinians, the Ukrainians and Russians, the Catholics and Protestants, the Indians and Pakistanis, etc.

And, of course, every corner of “Death Road,” which lived up to the hype of being the most dangerous road we traveled, though it felt much safer because of the relative lack of traffic. The simple concept of it is ludicrous — on our journey to it and up it we went from about 1,000 feet of altitude to 15,000 feet, and then back down, and nearly every turn felt like an opportunity to go careening hundreds of feet into a canyon. Even more asinine is that, not long ago, cars — and trucks — passed on this road in both directions. It was hard to wrap my head around. But it happened. And it was not hard to understand how so many people died so regularly when you see it.

As the trip neared its end I noticed a few things that gave me pause. For one, the various ailments I had been feeling magically disappeared about three days in — the eye twitch, the stomach issues (llama notwithstanding), the flash headaches — all gone. Not minutes after this occurred to me I got a notice from Apple on my phone that my screen time was down 81% that week. A poignant reminder of what the cost of doing this work, sitting in front of a computer all day, and living in a state of high stress has on the body.

To say I'm glad I went would be the understatement of the year. If anything, the many emails I got urging me to do the full trip rather than come home early left me with some pangs of regret that I only did six days instead of 10 or 17, but the truth is I’ve had a long winter on the road — suburban Philly, Kentucky, upstate New York, and West Texas all in the last few weeks — and my need to be home was too overbearing for me to enjoy even a few more days in the saddle.

Before we left the top of Death Road I plastered a Tangle sticker onto the famous Death Road sign, underneath a few others already there, hopeful that one day I’ll hear from a reader or random friend who runs into it. Our last leg together was spent driving from the top of Death Road down into La Paz. Like everything else on the trip it was beautiful beyond words. This portion was also freezing cold and rainy. After passing through a toll, Willy pulled over on the side of the road and ordered some fried cheese and a hot corn on the cob, took a few bites, and then promptly zipped the rest inside his jacket to warm himself up.

As we passed through the land between Death Road and La Paz some kind of hypnosis in the beauty of it all apparently took over and not a single one of us managed to capture a picture or video of that portion of the ride. Which was fitting and in some ways poetic. Willy said he felt like he should cry, and I damn near did — it looked like some combination of Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones and I'm running out of adjectives for what we saw so I'll just go ahead and quit.

That night, we enjoyed a fancy rooftop dinner in our hotel, which had floor-to-ceiling windows that showcased a panoramic view of La Paz. After dinner, I “forced” (they were tired, but it didn’t take too much convincing) Marco and Willy to hit the town with me, trying to soak up my last few hours before a 3 a.m. flight to Bogotá which would then take me to my connection to Fort Lauderdale and then ultimately back home to Philly. The woman at the front desk of our hotel suggested a local hostel bar and when we arrived the “security” — an Irish woman in the middle of La Paz — demanded our passport numbers, so we wrote in some random digits on a clipboard and passed through, all laughing to each other.

It was what you'd expect out of any old hostel bar. We had a few beers and reminisced while the DJ played the most cliche American hits you could think of. Every language and accent imaginable echoed through the room and in just an hour or two we met travelers from as far away as Australia. I spoke to a young Santa Cruz local who told me about his dreams of moving to Iowa to join his parents who had become surgeons there — he was lovingly describing the flat farmlands and relative quiet. Nothing against Iowa, but after the week I had just had, I was having a hard time processing how anyone in his shoes would want to leave this gigantic bustling city surrounded by so much beauty.

When I asked him why he wanted to go to Iowa, this 23-year-old Bolivian looked at me like I was simple and responded in clear and plain English: "Because my life there would be a lot better." It was a straightforward reminder of all we’ve got to be grateful for.

We watched a dance competition take place on the bar that included two gigantic drunken shirtless Irishmen who had the whole room laughing and earned a well-deserved second place, right behind the Australian woman who did a handstand and then the worm down the actual bar and basically shut the whole thing down before it even started. Willy paid our tab and I gloated that I managed the whole trip without converting a single U.S. dollar and successfully mooched from my cousins til the very end.

When we got back to our hotel my cab to the airport was already waiting, so we all hugged and said goodbye and told each other we loved each other and promised to never stop telling stories about our trip. I fell asleep in the cab to the airport and then woke up and fell back asleep periodically for another full day through various forms of transportation until magically I was in my living room in Philadelphia.

One of my pet peeves about foreign travelers is that they often spend a few days in one place and then talk about it as if they know it intimately, and in my experience it takes months and often years or decades to really know a place. I won’t pretend to know much about Bolivia after spending six days there, but I can tell you a few things I feel quite sure of:

I’ve visited a number of countries and Bolivia was the most stunningly beautiful and ecologically diverse place I’ve ever been. The typical local we encountered was calm and kind and soft spoken. Off the bike, there wasn’t a moment I felt unsafe. Bolivian street food would benefit a great deal from tortillas. The mix of dense cities populated with urbanites and open land of scattered indigenous residents somehow carried a specific cultural throughline that you could feel but not quite touch. The gap between rich and poor was wider than I’ve seen in most places, and the poverty had many faces — the smiling and the broken. I’d go back, in a heartbeat, and I plan to, having only really scratched the tiniest of surfaces. I was left wanting much more.

Lico, Linda, Willy, and Marco carried on — I managed 6 days of the 17-day trip they had signed up for. After I left, the riding apparently got quite a bit easier and the tourism a lot more interesting. They've gone on to see the remarkable Salt Flats (which contain roughly half of the world’s lithium reserves, a geopolitical story in the making), the rich silver mines where indigenous Bolivians are working in horrific conditions, the train graveyards of Butch Cassidy legend, and a few Che Guevera historical sights. As I write this sentence I believe they're somewhere between Potosi and Sucre, though I can't be sure. I’m excited to hear their stories when the trip ends, though I know they’ll never be able to quite pass the experience on to me with words alone, even though I experienced half of it alongside them. I think of them each time I get up from my desk in my shared office space here in Philadelphia to walk to the kitchen and get some water, where — inexplicably — a giant motorcycle is mounted to the floor.

This was, without question, the most adventurous and remarkable trip I've ever been on, and even with the inherent danger of motorcycles and the potential pitfalls of Bolivia taken into account I give it my full endorsement. You can find Chris's company Bolivia Motorcycle Tours here and please don't hesitate to book it and go. You won’t regret it.

Supporting us.

Last week, our prices officially went up from $50 per year to $60 per year. Anyone who was already subscribed got locked in at the "legacy" price for good, but we got hundreds of emails from people saying that they wanted to pay the new price to support our work. It was an incredibly gracious response, and we promised we'd let you know how to do that once the price point changed. You can now go to your account, click "change" under member, and then pick the new $60/year tier. You can do that by clicking here (you have to be logged in). Thank you!