By Stout Cortez

Ahead of Thanksgiving week, I’m thinking back on many November Thursdays spent around the table — sometimes at my grandmother’s house, sometimes at my parents’ house, sometimes far away and improvisational (like the microwaved hen my mom prepared when we visited my sister in France) — but always surrounded by family.

The meals were loud when I was younger, and filled with the opinions and stories of older aunts and uncles (usually uncles), arguing about things I didn’t understand. Over time, the meals became less crowded. The noise at the table got quieter. The older generation moved away or passed on and all the kids in my generation grew up, moved away, and have yet to have children of their own. Now, my grandparents are all gone, and with them many of their children — those same aunts and uncles who always left me entertained and confused.

But this isn’t a sad essay.

I’m thankful for those memories and the stories and the jokes old men tell. One uncle in particular had a penchant for these long, slow, Norm-Macdonald-style jokes that have too many moving parts and ended in a complicated and underwhelming pun. I swear to you, I’ve never heard any of his jokes anywhere else. I like to imagine he went back home to Indiana and worked on them for a year, pondering over maximally aggravating plays on words between case deliberations in his judge’s chambers, then recited them to us at our family gatherings — with far too much pride — just to see the pained, unwilling smile on my dad’s face and my adolescent bewilderment. For all I know that’s true.

Last year, over the course of a week, I came up with such a joke. And I’d like to tell it to you all now for your own underwhelmed bemusement.

This one’s for you, Uncle Mike. I hope, if you’re reading this, that you’re not too offended by the way I implied you were dead.

Joe and Bob are just a couple of regular guys, with regular jobs as appliance repairmen, with a regular monthly book club where they discuss foundational early-20th-century texts.

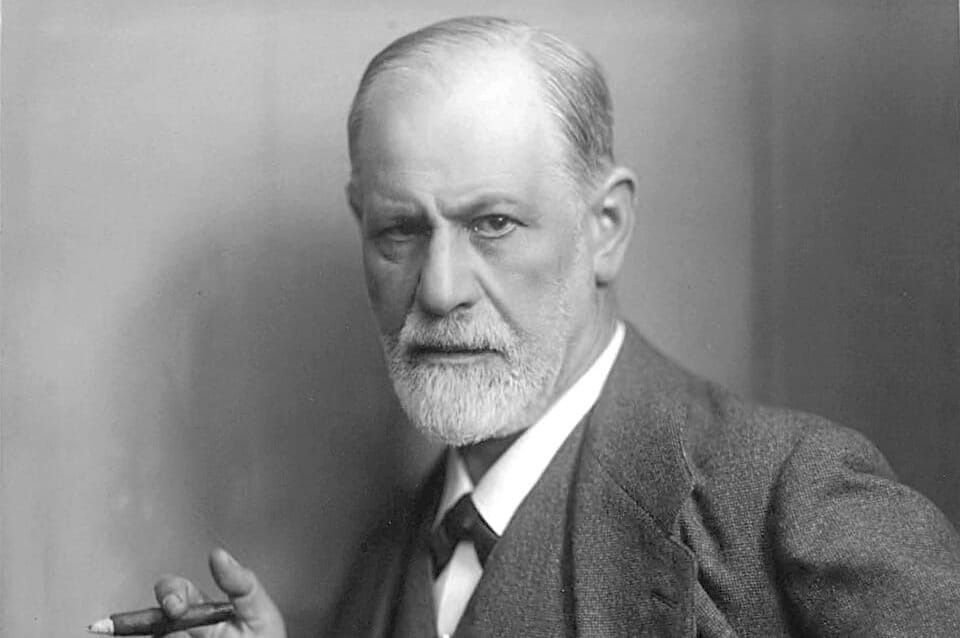

Bob comes over to Joe’s house for one of their book club meetings, sixer and frozen pizza in hand, Sigmund Freud’s The Ego and the Id tucked under his arm. He knocks on the door, Joe answers, and he steps inside.