I'm Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum on the news of the day — then “my take.”

Are you new here? Get free emails to your inbox daily. Would you rather listen? You can find our podcast here.

Today’s read: 15 minutes.

Online shopping this holiday season? Protect your transactions with this easy tool.

Using a VPN is a powerful tool for keeping your online banking secure. What’s a VPN? It sounds techy but don’t despair — it’s a super simple tool that will mask your IP address and shield your online activity.

Think of your IP address like the address of your house — just as your home address tells people where to send letters or packages, an IP address tells websites, apps, and other devices where to send information you’ve requested.

A VPN like Surfshark can protect your sensitive information by encrypting your internet traffic, making it extremely difficult for hackers or third parties to intercept or steal your data. And it’s never been easier to start using one.

Tangle News readers can get it now for just $1.99/month (87% off), plus enjoy 3 extra months free.

*Our sponsors help keep Tangle free — thank you for supporting them when you feel they could be useful to your life.

“I miss being homeless.”

On Friday, we published a piece from A.M. Hickman about his experience as a self-described vagabond, hobo, and hitchhiker in the United States. Hickman’s story is receiving a wide range of reactions, from praise for his writing to criticism of his ideas. As always, we love publishing essays like this that offer fresh, engaging perspectives and drive dialogue and debate. You can read Hickman’s story here (paywalled for free subscribers).

Quick hits.

- President Donald Trump released his National Security Strategy document, outlining his foreign policy vision. The document calls for U.S. supremacy in the Western Hemisphere and increased strength in the Indo-Pacific, while also calling on Europe to address issues related to demographic change. (The release)

- The Supreme Court announced that it will hear arguments on Trump v. Barbara, a case challenging the Trump administration’s executive order ending birthright citizenship in the U.S. (The case) Separately, the Supreme Court will hear arguments on Monday in a challenge to President Trump’s attempt to fire Rebecca Slaughter as Commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission. The case could roll back protections against removal for members of independent agencies. (The case)

- Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth said he would not commit to releasing footage of the U.S. military’s second strike on an alleged drug boat in the Caribbean in September, which has prompted heightened congressional scrutiny over the past week. (The latest)

- Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said he expects the second phase of the Israel–Hamas ceasefire in Gaza to commence soon, though he did not specify the timeline. (The comments)

- The Trump administration will reportedly announce $12 billion in aid to U.S. farmers on Monday afternoon. Most of the package will go toward the Farmer Bridge Assistance program, which supports U.S. crop farmers. (The aid)

Today’s topic.

The new hepatitis B vaccine guidance. On Friday, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted 8–3 to eliminate a longstanding recommendation that all newborns receive a first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine. The committee instead recommended that women who test negative for hepatitis B should consult with their doctors to determine whether their babies should be given the first dose of the vaccine, suggesting that the initial dose be administered after the infant is at least two months old. The committee voted on the change after it heard presentations from several vaccine critics; no Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) subject-matter experts presented to the panel.

Back up: ACIP develops recommendations for the CDC on safe vaccine use and the U.S. adult and childhood immunization schedules. The committee’s recommendations also impact which vaccines are covered by insurers and federal health programs. In June, Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. fired all 17 committee members, claiming that they were not capable of independently evaluating the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Kennedy has since appointed new members to ACIP, many of whom have criticized vaccines.

Hepatitis B is a virus that can cause liver infection and lead to severe liver damage, liver cancer, and death. Prior to Friday’s vote, the CDC had recommended for over three decades that infants receive the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine within 12 hours to newborns with infected mothers and within 24 hours to all other newborns. Doctors and public health experts have widely credited the vaccine with curbing the virus’s prevalence.

ACIP members who supported the change said that the risk of newborns contracting the virus if their mothers test negative is very low and called for more substantive studies to determine whether the vaccine is safe for newborns, though past studies have found that it is safe. Dr. Tracy Beth Hoeg, the acting director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at the Food and Drug Administration, argued that children should not receive the hepatitis B vaccine at all.

Many medical groups, doctors and public health experts criticized the vote, saying that ACIP has become ideologically driven under Secretary Kennedy, a longtime vaccine skeptic. Dr. Debra Houry, who resigned as the CDC’s chief medical officer in August, said she was “very concerned” about the future of the agency under Kennedy, calling it “heartbreaking to see this science-driven agency turn into an ideological machine.” Others warned that the recommendation change will lead to an uptick in hepatitis B. Acting CDC Director Jim O’Neill will decide at a later date whether to accept ACIP’s new guidance.

President Donald Trump praised the committee’s new guidance, calling it “a very good decision.” He also announced that he had signed a presidential memorandum directing the Department of Health and Human Services to conduct a review of childhood vaccine schedules in other countries and “better align the U.S. Vaccine Schedule, so it is finally rooted in the Gold Standard of Science and COMMON SENSE!”

Today, we’ll survey arguments from the left, right, and subject-matter experts about ACIP’s vote, followed by Executive Editor Isaac Saul’s take.

What the left is saying.

- The left criticizes the committee’s decision, saying it has no medical justification.

- Some say Kennedy is accomplishing his anti-vaccine goals.

In The Washington Post, Leana S. Wen said “the CDC’s change to hepatitis B vaccination is even worse than it seems.”

“On the bright side, the policy doesn’t change care for the babies at highest risk: Infants born to mothers known to have hepatitis B will still receive the vaccine, along with a preventive immunoglobulin, to reduce the risk of perinatal transmission. And families who want their newborns to receive the hepatitis B shot can still choose it and have it be covered by insurance,” Wen wrote. “But this new approach attempts to solve an issue that doesn’t exist. There is no evidence that the birth dose is unsafe, and no evidence that waiting until two months offers any advantage to safety or efficacy.”

“Plus, transmission doesn’t just happen mother-to-baby. Hepatitis B can spread through casual contact, including shared household items, small amounts of blood or saliva on toys and surfaces. Everyday interactions such as sharing spoons or cups, handling a baby with microscopic cuts on one’s hands or even inadvertently mixing up toothbrushes can be enough to transmit the virus,” Wen said. “Universal newborn vaccination has helped drive childhood hepatitis B infections down from 18,000 cases in 1991 to just about 20. Why change a policy that has been so effective?”

In The Bulwark, Jonathan Cohn wrote “this is what it looks like when RFK Jr. wins.”

“Exactly how (or when) the new hepatitis B vaccine guidelines would change actual behavior is difficult to say. It’s not as if anybody forces parents to get their kids vaccinated today, the proof being that some parents decline the hepatitis B shot for their kids already,” Cohn said. “But there’s a reason both supporters and critics of vaccines fight about these guidelines: They really do affect decision-making. They signal to parents what top scientists believe is the smartest course of action. And they can influence physicians, who look to bodies like the CDC to undertake the kind of ongoing, exhaustive literature and research reviews they don’t personally have time to do on their own.”

“Kennedy has gone well beyond recruiting some contrarians with novel perspectives. He has populated the advisory committee almost exclusively with people with records of attacking vaccines in one way or another,” Cohn wrote. “The best-case scenario is that the health system’s collective muscle memory on hepatitis B is strong enough to keep current practices going… But in a highly politicized environment where the president and the nation’s top health care officials are constantly talking down vaccines, some people are bound to take their word seriously.”

What the right is saying.

- Many on the right say the change simply aligns the U.S. with other countries.

- Some say the value of the CDC acting as a vaccine authority is limited.

In The Daily Caller, Emily Kopp said ACIP’s decision “align[s] childhood vaccination schedule with other high-income nations.”

“The pivot away from a universal shot within hours of birth aligns the U.S. policy with the approach of 24 other high-income nations that recommend a first dose at two months old or three months old,” Kopp wrote. “Though the American Hepatitis B vaccine schedule now resembles those of other Western nations, and despite the continued availability of the vaccine to all mothers, the legacy media characterized the decision as a reckless upheaval. ‘CDC panel makes most sweeping revision to child vaccine schedule under RFK Jr.,’ a Washington Post headline blares.”

“All of the committee members agreed that the committee lacks key data on the risks and benefits. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) did not require randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials of the two Hepatitis B vaccines that it approved for the first day of life in the 1980s, according to FDA Acting Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Director Tracy Beth Høeg,” Kopp said. “‘The data that we used to approve the Hepatitis B vaccines … were based on studies that had a very short-term follow-up and no control group,’ said Høeg… [She] identified anaphylaxis and fever as rare side effects.”

In Cato, Jeffrey A. Singer wrote about “why medical guidance shouldn’t come from Washington.”

“Many professional medical and public health organizations oppose the decision, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Public Health Association, and the American Pharmacists Association, as well as numerous clinical researchers and medical specialists,” Singer said. “This episode highlights a deeper institutional problem. As I have written previously, ‘Members of the medical and scientific community who have long supported an active government role in health issues likely never expected that a controversial figure like Robert F. Kennedy, Jr… would become the leader of the country’s public health system.’”

“This underscores why… Congress should return the CDC to its original purpose: being a focused partner that assists states in tracking and controlling infectious diseases. The federal government should leave medical and scientific debates to scientists and clinicians. By involving itself in these debates, the CDC fosters the impression that there is a single ‘right answer’ to complex, nuanced questions,” Singer wrote. “If there’s a silver lining, it’s that controversies like this may finally encourage clinicians, researchers, and patients to rely less on federal pronouncements and more on diverse, independent medical expertise.”

What medical professionals are saying.

- Medical professionals uniformly criticize the change in guidance, saying it has no scientific basis.

- Others suggest the change will put an undue burden on parents.

The American Association of Immunologists said they were “extremely disappointed” in the recommendation change.

“The science behind the hepatitis B vaccine is robust and well-established. The hepatitis B vaccine has an exceptional safety record, and it is extremely effective at preventing lifelong, chronic infection in infants who might otherwise be exposed to the virus during childbirth or early life,” the group wrote. “More than 90% of infants who contract hepatitis B at or around birth will go on to develop chronic hepatitis B. Of those, roughly one in four face a premature death from liver disease or liver cancer. The impact this has on families, and the healthcare system, can be effectively mitigated with use of vaccines.

“Delaying the vaccine would mark a dangerous departure from decades of achievement in preventing hepatitis B infection and its complications. Recent independent analysis warns that even a modest delay could result in a substantial increase in preventable chronic infections, liver cancers, and deaths. Now is not the time to undermine confidence in one of the most successful vaccine-based public health interventions in modern history.”

In Your Local Epidemiologist, Katelyn Jetelina shared her “key takeaways” from the vote.

“In the end, the committee voted to move America back to pre-1991 by removing the universal vaccination recommendation for the Hepatitis B infant dose despite no new evidence of harm and ignoring clear benefits. They also recommended that parents ask clinicians for an antibody blood test to determine the need for subsequent doses, even though there’s no evidence that this works,” Jetelina said. “This ultimately shifts the burden to clinicians and parents and abdicates the responsibility of the recommending body.”

“Where this goes from here depends on what happens next. If confusion dominates headlines and clinical practice and falsehoods fill the void, the consequences will be serious. But if we respond the way we saw many do today — pushing back with clarity, authority, evidence, coordination, and grassroots strength — the harm can be contained and minimized,” Jetelina wrote. “Unfortunately, our work is not done. There will be increasing confusion about evidence-based vaccination options for parents, clinicians, hospital systems, and schools. This will decrease vaccination coverage, leading to more disease and unnecessary suffering.”

My take.

Reminder: “My take” is a section where we give ourselves space to share a personal opinion. If you have feedback, criticism or compliments, don't unsubscribe. Write in by replying to this email, or leave a comment.

- I’m not a health expert, but as a new parent, this new recommendation creates more confusion than clarity.

- The commentators I trust give me good reason to oppose ACIP’s recent change.

- I always seek out multiple opinions, but Kennedy’s Health Department isn’t modeling good scientific dialogue.

Executive Editor Isaac Saul: With a 10-month-old baby at home, I am in the thick of the frustration, fear, and confusion of the vaccine schedule.

As a parent, even seemingly uncomplicated decisions become complicated. “Vaccinate your kid” seems obvious until you try to do basic research on the safety of a vaccine and get bombarded with stories of kids dying 24 hours after a shot or internet rumors about how some former voting member of ACIP made millions with Big Pharma. Even for a professional information consumer like me, separating fact from fiction is a scary and fraught process.

This is intensified by the actual experience of vaccinating: holding an infant child down on a table while they get pricked and prodded, them crying in pain and then (often) experiencing a day or two of fussiness and fever. Are they okay? What have I done? Was this really worth it?

Since you are reading a politics newsletter right now, I am not going to give you or your children medical advice. Instead, I will speak to my own experience, and how some vaccination decisions for children feel less obvious than others. Getting a Covid vaccine for an infant, for instance, did not seem straightforward. Unlike with other vaccines, our doctor was much less forceful in her opinion about what we should do. Covid vaccines are new and less tested for infants, and Covid is often less dangerous for young children. My wife had Covid while she was pregnant, and our baby breast fed (so he was, theoretically, getting antibodies from her, since she was vaccinated and had the virus).

Before our son arrived, my wife and I decided on a process for making these decisions: We were going to pick one or two trusted sources outside of our medical team, and use the information from our doctors combined with those sources to make informed decisions. That way, we could try to ignore the firehose of information we encounter every time we open a social media app or turn on the news. For us, the source we leaned on most heavily was Emily Oster, the professional economist behind the best-seller Expecting Better and the parenting website Parent Data, who makes decisions through a data-first framework. Her educated opinion felt like a nice complement to the medical advice from our doctors, and she provided a trustworthy single source for the unavoidable questions that pop up during and after pregnancy.

To be candid: My wife and I didn’t seriously consider skipping the hepatitis B vaccine when our son was born. We had decided to lean on the wisdom of my wife’s doctor and Oster, who both said the decision carried close to zero risk and offered only upside. We might have had one drawn out discussion after our doula told us we could pass on the vaccine when my wife tested negative for the virus, but we didn’t see any compelling reason to question the advice of our medical team.

So this is the lens through which I’ve been watching this story unfold. Even though I’m not personally someone who would trust a government guideline above all else, I do think agencies like the CDC must present reliable, clear information for parents navigating these difficult decisions. Unfortunately, after picking new members for ACIP to ensure vaccine-skeptical outcomes like this, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is offering parents like me only more doubt and confusion.

To better understand the effects of the new panel’s first major decision, I turned to two public health commentators whose insight I trust: Dr. Leana S. Wen, an open-minded public health expert (who backed Kennedy’s push to remove fluoride from water), and Katelyn Jetelina (the epidemiologist behind Your Local Epidemiologist). Both were alarmed. Jetelina emphasized that the outcome is not as bad as some headlines make it seem, given that the vaccine will still be widely available and eligible for insurance coverage, yet her trepidation came through. She offered a worried but optimistic take on how public pressure and a few determined ACIP members were able to push back on the flimsiness of some of the claims presented to the committee and prevent a far worse outcome.

Wen instead focused mostly on the practical effects of the new guideline outcome: That parents will now be asked to test antibody levels in their children after the first of the vaccine’s three-dose series. After our two-day stay in the hospital after our son was born, we had a one-month check-up, a three-month check-up, and a six-month check-up. Paired with a couple of visits for a rash here or a fever there and various follow-ups with individual specialists, parents of even a healthy baby already end up going to the doctor eight or 10 times in the first ten months. Adding another infant blood draw, another doctor’s appointment, and more cost to the already overwhelming early infancy is — to me — pretty preposterous.

Meanwhile, I found the counterpoints to this view unconvincing. Some writers claimed the vaccine addresses a non-existent risk. The blogger streiff said, “Every expectant mother is tested for the virus when she is admitted for delivery and, if she is positive, the infant can be vaccinated then.” This simply isn’t true. The CDC recommends testing in the first trimester, not at delivery, and many mothers (including my wife) are only tested for hepatitis early on in pregnancy. That test is consulted during delivery — but a new test is often not administered if the mother was negative. That means new mothers could have become carriers for the virus and without knowing it.

Many commentators have also emphasized that this new guidance brings us in line with many other peer nations. But those nations are not really our peers when it comes to healthcare or population. Denmark, for instance, has universal healthcare, more consistent prenatal care, and perhaps most importantly, a smaller and much less diverse population than us (with a lower incidence of hepatitis B). Our healthcare systems and populations are different enough that I think looking to Denmark for guidance is a self-defeating task. We should do what works for us, not for them.

Again: I’ll re-emphasize that my perspective is not expert, and that a variety of expert viewpoints is good for new parents. Secretary Kennedy often promotes a similar message. But the actions of the department he leads actually shut down genuine scientific exchange of ideas, which to me is the most frightening aspect of ACIP’s decision. For their latest meeting, Kennedy broke from tradition by refusing to allow presentations from CDC subject-matter experts. So while scientists who study the hepatitis B vaccine for a living were shut out from deliberations, a lawyer and longtime Kennedy ally named Aaron Siri (who has petitioned the government to stop distributing the polio vaccine!) was able to state his case.

This is decidedly not scientific debate; it’s working towards a desired outcome. And while this particular outcome isn’t the worst-case scenario, it is another worrying step for Kennedy’s Health Department — and it will have real practical implications for parents and infants who are unlucky enough to encounter hepatitis B in the coming years.

Take the survey: How does the latest change affect your trust in CDC vaccine recommendations? Let us know.

Disagree? That's okay. Our opinion is just one of many. Write in and let us know why, and we'll consider publishing your feedback.

Our latest live event.

Ever wonder what a Tangle live event is like? Now you can find out — we just released the full version of our Irvine, California, discussion on YouTube. You can check that out below, and we'll see you at the next one!

Your questions, answered.

Q: Is Pete Hegseth the Secretary of Defense or War? Is that renaming official? If so, why does Tangle not use it?

— Adam from Denver, CO

Tangle: In a sense, he’s both — and no, the rename is not official. In the White House’s September 5 fact sheet announcing the Trump Administration’s restoration of the name “Department of War,” the title is officially stated to be “secondary.” A secondary title is one that agencies can use to refer to themselves in official government communications and often matches their already utilized informal names, and are usually inversions (like Justice Department instead of Department of Justice) and are often abbreviations (like DOE for Department of Energy). Only Congress has the authority to officially rename a federal department or agency.

At Tangle, we have a policy of using the official name of the department as a default, but we often use informal titles so our reporting sounds more natural and less repetitive. For example, we might occasionally refer to the Department of Defense as the Pentagon (the department’s headquarters), and we could refer to the Central Intelligence Agency as Langley (the Virginia city where the CIA is headquartered). But when it comes to a person’s title, we’re always going to use the official name; that means we’re not going to write Secretary of War, just as we’d never write Secretary of the Pentagon.

Let’s broaden the scope and ask a tougher question: Would Tangle ever write the Department of War? Maybe, but it’s trickier for us to adopt. First, informal names are often determined by popular usage, not top-down dictum, so we’re resistant to follow a government order to change a title we’ve been using without issue all our lives. Second, the Department of Defense has a history behind its name. The Department of War that existed from 1789–1947 is actually not the exact same as the modern DoD. At first, that agency only oversaw the Army, while the Navy had its own cabinet-level department. President Truman consolidated the departments, along with the new Air Force, under the “National Military Establishment” in 1947 — then he restructured them again into the “Department of Defense” in 1949.

The change also emphasized the military’s use as a deterrent and deemphasized “war” as a cabinet-level pursuit for our government, so bringing back the older title seems like a step in the other direction. Maybe we’ll write it occasionally, but it’s not a title we’re eager to employ.

Want to have a question answered in the newsletter? You can reply to this email (it goes straight to our inbox) or fill out this form.

Under the radar.

Last week, U.S. Steel announced that it plans to resume steelmaking at a facility in southwestern Illinois that has not produced steel for two years. The company had planned to continue reducing operations at the plant before the Trump administration intervened to block the move in September; U.S. Steel now says that demand for steel has risen enough to warrant a restart in production, particularly as the company completes renovations at other steel mills. “We are confident in our ability to safely and profitably operate the mill to meet 2026 demand,” U.S. Steel CEO David Burritt said. The Wall Street Journal has the story.

Holiday Shopping? Don't Skip This $1.99 Security Step.

Online shopping this holiday season?

Protect your transactions with a VPN.

It masks your IP address and encrypts your internet traffic, making it extremely difficult for hackers to intercept your data.

Tangle readers get Surfshark for just $1.99/month (87% off) plus 3 extra months free.

Numbers.

- 1965. The year the hepatitis B virus was discovered.

- 1981. The year the Food and Drug Administration approved the first hepatitis B vaccine for human use.

- 99%. The percent decrease in pediatric hepatitis B incidence since 1991.

- 17,000. The approximate number of babies born to women with hepatitis B annually in the U.S.

- 80%. The approximate percentage of liver cancer globally that is caused by chronic hepatitis B and C.

- 63%. The percentage of U.S. adults who say they are highly confident that childhood vaccines are effective at preventing serious illness, according to an October 2025 Pew Research survey.

- 5% and 4%. The percentage of U.S. parents who reported that they skipped and delayed, respectively, the hepatitis B vaccine for at least one of their children, according to a July-August KFF/Washington Post survey.

- 8% and 5%. The percentage of U.S. parents who call themselves supporters of the Make America Healthy Again movement who reported that they skipped and delayed, respectively, the hepatitis B vaccine for at least one of their children.

The extras.

- One year ago today we had just published a post-election Friday edition asking “What is a liberal?”

- The most clicked link in Thursday’s newsletter was the suspect arrested in the Jan. 6 pipe-bomb case.

- Nothing to do with politics: You didn’t ask, but here’s an 85-minute video on the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge.

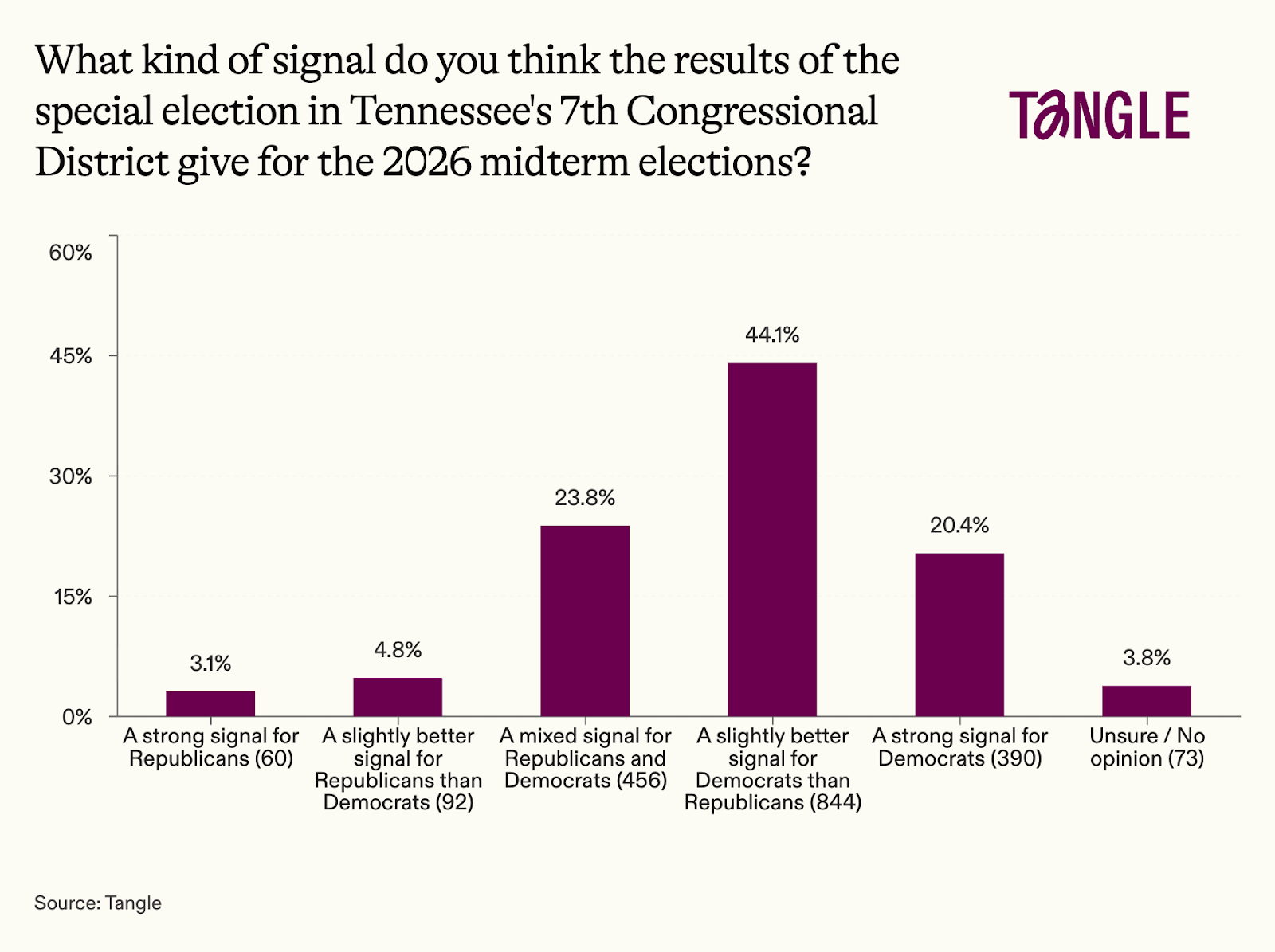

- Thursday’s survey: 1,915 readers responded to our survey on the special election in Tennessee with 44% saying the results provide a slightly better signal for Democrats than Republicans. “If the Democrats can’t pick more palatable candidates, it won’t matter that there's fairly widespread discontent for the current Republicans,” one respondent said. “I don't put too much stock in off-cycle special elections held in the middle of the holiday season,” said another.

Have a nice day.

Roughly 40% of families in the Standing Rock Reservation live below the poverty line. Tribal-owned energy group SAGE had an idea for an initiative to return investment: promoting electric vehicle access in the rural community where gas prices significantly raise the cost of living. Through a regional initiative called “Electric Nation,” SAGE spent three years installing EV chargers along the border of North and South Dakota, and the project wrapped at the end of November. “Even though tribes have been skipped over and underfunded, they’ve become a keystone to filling in infrastructure gaps in rural America,” Len Necefer, a Navajo citizen and energy expert, said. The New York Times has the story.

Member comments