I'm Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum on the news of the day — then “my take.”

Are you new here? Get free emails to your inbox daily. Would you rather listen? You can find our podcast here.

Today’s read: 15 minutes.

Dehydrated? This Might Be Why.

Forget everything you thought you knew about hydration. New science reveals water alone isn’t enough. In fact, if you're guzzling glass after glass and still feeling tired, foggy, or crampy—your body might be missing key electrolytes.

That’s where NativePath Hydrate comes in. It’s a doctor-formulated electrolyte mix designed to restore cellular hydration fast, without the sugar, dyes, or sketchy additives found in sports drinks.

Especially helpful if you drink coffee or alcohol… sweat often… or have the MTHFR gene mutation (which can block proper absorption of essential minerals).

Bonus: It actually tastes amazing.

Thousands are making the switch—and feeling more focused, energized, and “even keeled” within minutes.

👉 Learn why water isn’t enough—and why NativePath Hydrate is the smarter way to hydrate

*This is a message from one of our sponsors.

A note about today’s newsletter.

Recently, we’ve been discussing all the topics we want to cover in the Tangle format that might not fit neatly into the 24-hour news cycle. So this month, we’re experimenting a bit by picking up some issues we find fascinating and politically relevant — and that we think our readers would be interested in. Let us know what you think, and feel free to write in or comment with topics you’d like to see us cover outside the day-to-day news cycle!

Before you read.

Today’s piece includes detailed discussions of suicide. If you are having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or go to SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for a list of additional resources.

Quick hits.

- A federal appeals court issued a preliminary injunction blocking the Trump administration from deporting a group of alleged gang members from Venezuela under the Alien Enemies Act. (The ruling) Separately, a federal judge ruled that President Donald Trump and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth violated federal law by deploying National Guard members and Marines to Los Angeles in June. The judge barred the administration from further use of federal troops for domestic law enforcement except in limited cases. (The decision)

- President Donald Trump announced the U.S. Space Command headquarters will be located in Alabama, reversing a decision by former President Joe Biden to keep the command at its temporary headquarters in Colorado. (The announcement)

- Washington, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser (D) issued an executive order requiring local coordination with federal law enforcement “to the maximum extent allowable by law within the District.” (The order) Separately, President Trump said he would deploy National Guard troops to Chicago and Baltimore, though he did not specify the timing of the deployments. (The deployment)

- A district judge ruled that Google could not enter deals to make it the exclusive search engine on devices and browsers but rejected a Justice Department request to force the company to sell its Chrome web browser. The ruling followed an earlier determination that Google had illegally monopolized the online search market. (The ruling)

- A U.S. military strike killed 11 people on a vessel from Venezuela allegedly carrying illegal narcotics. The Pentagon has not released further details about the attack. (The strike)

Today’s topic.

The debate over physician-assisted suicide. In recent years, several U.S. states and a number of countries have legalized Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID), also known as physician-assisted suicide or physician-assisted death. While definitions vary, the practice generally allows people facing imminent death from a terminal illness to end their lives by administering drugs with support and supervision from a doctor (or team of doctors). In some countries, people with certain chronic illnesses and disabilities are also eligible for MAID. As more states consider legalizing the practice, proponents and opponents have raised ethical concerns about how MAID is regulated — and whether it should be legal at all.

Back up: MAID is legal in 11 U.S. states and Washington, D.C., and 17 states are considering legislation to legalize MAID in some form. Oregon was the first state to legalize the practice in 1997, and most other states that have legalized MAID have based their legislation on Oregon’s law.

MAID is sometimes conflated with euthanasia, but the two are different forms of assisted death. The former involves the patient administering the life-ending drugs themselves, while a healthcare provider administers the drugs in the latter case. Euthanasia is illegal in all 50 states.

The practice of MAID is formally opposed by most major medical groups, including the American Medical Association, American College of Physicians and World Medical Association, primarily on the grounds that it violates medical providers’ pledge to “first, do no harm.” However, some organizations have come out in support of legalizing MAID; for instance, the American Medical Women’s Association said in 2018 that it “supports the right of mentally capable terminally ill patients to advance the time of death that might otherwise be a protracted, undignified, or extremely painful death.”

While access to MAID remains relatively limited in the United States, other countries have adopted far more permissive laws. In 2016, Canadian lawmakers legalized MAID under strict conditions, including that patients be over 18, mentally competent to consent to death, and expected to die in the “reasonably foreseeable” future. In 2021, the “reasonably foreseeable” provision was removed, allowing Canadians with “irremediable conditions,” including chronic sickness or physical disabilities, to seek out MAID.

The change increased concern among the practice’s opponents that some people would pursue assisted death in response to unmet medical, financial, or social needs. However, supporters of the practice have maintained that Canada’s law offers relief to people who are suffering acutely, even if their death is not imminent.

Today, we’ll break down arguments for and against MAID. Then, Managing Editor Ari Weitzman gives his take.

What opponents say.

- Many opponents of legalizing MAID say that it should be rejected for the same reasons we reject other forms of suicide.

- Some suggest that assisted suicide undercuts the dignity of life.

- Others worry that legalized MAID will compel people to choose death over reliance on faulty healthcare systems.

In First Things, Audrey Pollnow wrote “suicide prevention must be for everyone.”

“It’s tempting to imagine that in an end-of-life context, MAiD isn’t ‘really’ suicide because the person who requests it was already going to die — but common sense shows that this is false. When someone suffering from a terminal illness kills herself in any other way, we call this suicide. We mourn these suicides, and we rightly try to prevent them,” Pollnow said. “Of course, some people seem to think that in an end-of-life context, suicide can somehow be a legitimate choice. They imagine that this is a special situation, that suicide is justified when death is proximate and when the final months of your life may involve great suffering… But the reasoning here faces a terrible problem: It implies that most suicides are legitimate.”

“If we want to take suicide prevention seriously, we can’t act as though autonomy and pain management are legitimate reasons for suicide — not in an end-of-life context or any other context. We must either insist that suicide is not the answer, even when you’re suffering and even when it looks attractive, or we must give up on suicide prevention altogether. Because suicidality almost always involves the kind of suffering that makes it seem attractive to end your life,” Pollnow wrote. “Fundamentally, offering MAiD to the terminally ill implies at least one of two unacceptable conclusions. It implies that we should offer suicide to anyone who wants it, or that we should offer people suicide on the basis of disability.”

In America Magazine, Noël Simard argued “medical assistance in dying is not what our most vulnerable people need.”

“Expanding the eligibility of MAID to persons with mental illness and the possibility of advance requests threatens the dignity of the human person and the common good, while raising many questions that have no easy answer,” Simard said. “For instance, do we have tools to measure the suffering of someone living with mental illness? At what stage of mental illness will it be possible to offer MAID, and who will be entitled to determine that moment? While we know that mental illnesses are often impossible to cure, how can we ensure that all treatment options have been offered, and how can we know that all reasonable treatment options have been exhausted?”

“When a person decides not to be treated for cancer or not to receive dialysis because the treatment is no longer beneficial or has become too burdensome, it is a personal choice. This choice may be justified, even with the risk that the person’s life may end more rapidly,” Simard wrote. “In the case of euthanasia, there is no risk. Here is certainty: The person will die immediately. And what about the burden for the person who must carry the proxy or make the decision in that individual’s place? The autonomy of the sick person is not absolute. There are limits to the exercise of freedom when the common good or fundamental values, such as the sanctity of life and the person’s inherent dignity, are jeopardized.”

In The New York Times, Louise Perry criticized “the perverse economics of assisted suicide.”

“Those who support the legalization of assisted suicide have a bad habit of using a motte-and-bailey style of argumentation. From their easily defended motte, they insist that a person with a terminal illness who fears a painful and undignified death should be able to seek medical assistance and the company of his loved ones if he decides to make an early exit. That argument seems logical enough to most of us and compassionate. But then there’s the bailey: what assisted suicide actually looks like in many of the countries that have adopted it,” Perry said. In Canada today, “young people with potentially long lives ahead of them are choosing state-facilitated death.”

“There is a very clear problem with assisted suicide in its new guise: The state, with its almighty power, is tasked with both paying for the support of the old and disabled and regulating their dying. Encouraging citizens to accept [this system] may seem like a cost-saving measure at a time when the financial burden of their care has never been greater,” Perry wrote. “For all of the problems with the American health care system, its largely privatized structure means that it is less vulnerable to these perverse incentives. The moral peril is greatest in countries like mine, in which a socialized health care and pension system has a strong incentive to winnow out its most expensive users.”

What proponents say.

- Many proponents of legalizing MAID argue the practice gives crucial autonomy to people facing terminal diagnoses.

- Some cite personal experiences with MAID, describing it as a dignified end of life for a loved one.

- Others question why the government should have the power to restrict this choice.

In Newsweek, Anita Hannig made “the case for assisted dying.”

“Even as more states consider legislation that supports and enhances the practice, confusion and hurdles remain. The U.S. has the most restrictive assisted dying laws in the world. These laws often stifle patients who are either too sick or not sick enough to qualify for a prescription,” Hannig wrote. “To be eligible for assistance in dying, a patient must have a prognosis of six months or less to live, which excludes patients with painful and protracted — but not immediately fatal — conditions like Multiple Sclerosis. Patients must be capable of administering their own deaths, either by swallowing the lethal medications or pushing them through a feeding tube or rectal catheter.”

“Yet despite the roadblocks many patients must contend with — while their health is rapidly declining — there is a reason they persist. For many, an assisted death restores a sense of agency in a situation that made them feel trapped and powerless,” Hannig said. “As a society, we must ensure that assisted dying continues to be driven by the needs of terminally ill patients and that it remains just one of many ways to have a humane, dignified death. Yet as the population ages, many more people will confront diseases that don't respond to treatment and that are daunting and terrifying in their course.”

In CNN, Ginger Fairchild wrote “medical aid in dying was a blessing for my husband.”

“My husband, Matt Fairchild, a retired Army sergeant and Gulf War veteran, made the decision to seek medical aid in dying,” Fairchild said. “I am grateful he had the option to end his suffering. Matt loved life, and at only 52, he didn’t want to die. But after he went through nearly a decade of chemotherapy, radiation, hospitalizations and surgeries in a valiant attempt to cure the skin cancer that had spread to his brain, bones and lymph nodes, it was a blessing to give him the option to be at home and to take the medication to pass peacefully.”

“My hope is that this option is available to others as well. Unfortunately, for millions of Americans who depend on federally funded insurance and medical facilities, medical aid in dying is financially inaccessible, in large part due to a decades-old law that bans the use of federal funds to pay for this end-of-life care option,” Fairchild wrote. “There is no comparison between a mentally capable, terminally ill person who is going to die no matter what, and just wants to die peacefully, with loved ones by the bedside, and a mentally distraught person who prematurely ends their life via suicide, usually alone, often violently… Why should a state border or ZIP code determine whether you can die peacefully or whether you must die with needless suffering?”

In City & State, Richard Gottfried called MAID “a long overdue human right.”

“It has long been established in federal law and every state’s law that adults with decision-making capacity have the right to refuse medical treatment — including life-sustaining treatment,” Gottfried said. “We also have the legal right to require our health care provider to turn off or disconnect life-sustaining machines and tubes, knowing that the result will be death. With patient consent, a physician can order a high dose of morphine, knowing it will reduce the patient’s respiration and likely hasten their passing. I firmly believe that these fundamental human rights cannot be separated from medical aid in dying.”

“I understand that many people, including many legislators, are reluctant or squeamish about dealing with legislating matters related to death. It is an uncomfortable and often taboo topic, even though it eventually impacts us all,” Gottfried wrote. “But it’s outrageous for the government to tell its people that they can’t have autonomy over their own lives, just like it’s outrageous for the government to tell people who to marry or whether they should carry a pregnancy to term.”

My take.

Reminder: “My take” is a section where we give ourselves space to share a personal opinion. If you have feedback, criticism or compliments, don't unsubscribe. Write in by replying to this email, or leave a comment.

- The handful of countries that allow a version of physician-assisted suicide all do so very differently.

- Canada’s system feels far too permissive, which is reflected both in specific cases and in the data.

- I feel okay with what is happening in the U.S., but I have a visceral reaction against some of the cases protected by Canada’s MAID laws.

Two Fridays ago, Isaac, Kmele, and I discussed our reactions to Elaina Plott Calabro’s provocative piece in The Atlantic, “Canada is Killing Itself,” for Tangle’s Suspension of the rules podcast.

Calabro’s piece was striking in how it straightforwardly delivered details of such a ghastly subject matter. I was disturbed, especially by the example of a young man who chose MAID over cancer treatment out of a desire to avoid pain. I felt innately, viscerally opposed to the idea that death in these cases could be portrayed as treatment. But I was also aware that the article was written, skillfully, to be disturbing, and that my response to the piece was fundamentally emotional.

I came away from our podcast discussion eager to understand more: What don’t I know about Canada’s laws? How do they compare to the laws in the United States? And, most personally, why was my reaction to this essay so strong? I want to explore all of these questions, starting with more background context behind legal protections in the U.S. and Canada.

“Medical assistance in dying” is known in some countries as “physician-assisted suicide” or “assisted suicide,” though practitioners often prefer the term MAID to differentiate it from suicide’s “clouded” connotations. Nine countries, six Australian states and 12 U.S. jurisdictions have legalized some version of MAID and each country’s laws vary in their implementation. The countries and jurisdictions that have passed their own laws since Switzerland became the first to legalize medically assisted dying in 1937 have diverged from the Swiss system significantly.

The opposite is true in the United States, where Oregon was the first state to allow MAID. Laws in the 12 jurisdictions that have followed its lead all have the same core features: The patient must be an adult (18 years or older), have a terminal illness with a prognosis of six months or less, be able and willing to consent, and ingest the “lethal medication” themselves. The laws in the United States do not allow “euthanasia.” The same cannot be said of Canada.

Under the Canadian system, consenting adults with terminal conditions have a legal right to a medically assisted death through its “Track 1.” The same right is granted to those with “irremediable medical conditions” through its “Track 2.” In 2016, the Canadian Supreme Court codified the legal definition of an “irremediable condition” in its landmark Carter v. Canada decision: any medical condition (including illness, disease, or disability) that creates “enduring suffering that is intolerable to the individual in the circumstances of his or her condition.”

At this point, some readers may be unsettled by the apparent liberality of Canada’s system. I know this to be the case for me. However, the Carter decision (and Canada’s 2021 expansion to its two-track system) isn’t radical in a legal context; it’s downstream of a constitutional right afforded to all Canadians. The legal rights spelled out by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms — similar to the U.S. Bill of Rights — states that all Canadian citizens have a legal right to “life, liberty, and security of the person.”

That last right creates a troublesome dilemma, which the Carter decision wrestled with like this:

An individual’s response to a grievous and irremediable medical condition is a matter critical to their dignity and autonomy. The prohibition denies people in this situation the right to make decisions concerning their bodily integrity and medical care and thus trenches on their liberty. And by leaving them to endure intolerable suffering, it impinges on their security of the person.

If I were to present the strongest defense of what this ruling has produced, it would look like this: Under the right to “security of the person,” a Canadian citizen must be granted the ability to access their chosen medical assistance. Therefore, no person suffering intolerably can legally be denied this right to manage their own suffering, and many thousands of Canadians who were intolerably suffering were given the dignity of choosing how to end their lives.

Yes, one out of every 20 deaths in Canada is now medically assisted, but the rate in the Netherlands is even higher, 96% of MAID deaths are granted to terminally ill patients through Track 1, and there’s reason to believe Canada is not going to slip down the slope any further: Belgium has the most liberal MAID regulations in the world, extending euthanasia to minors and the non-terminally ill with psychiatric conditions, and its rate of medical death has leveled out at roughly 3%. Through a certain lens, MAID can be seen as the result of societal progress.

But that’s just not how I see it.

Canada’s death rate through MAID is surpassed globally by the Netherlands alone, and unlike its European counterparts, Canada’s death rates through MAID are rising. Meanwhile, its Parliament is currently considering expanding access to minors and the mentally ill. I don’t see societal progress; I see a country rushing to normalize a willingness to die. I see a perversion of language that allows this statement from Canada’s 2023 annual report to pass as a subtextual critique of the inadequately few people Canada’s doctors are killing each year and not the morbid paradox that it is: “In 2023, 2,906 individuals who requested MAID died before their request for MAID could be fulfilled.”

To put it differently: “2,906 individuals who requested to die died before they could be killed.”

Frankly, it upsets me to see language so effectively marshalled as a prophylactic from a harsh reality — “their request for MAID” for a demand to be killed. A smiling portrait on a three-foot casket. A rainbow band-aid over a gunshot wound. A comprehensible sanitization of an incomprehensible process, an end of all processes. The poet Rainer Maria Rilke likened a death scene to “the room with the open window and the fitful noises” — I recall being in that room, and I recoil at the thought of voluntarily placing myself back under the window, even if “unappealing sounds” replaces “fitful noises.”

With Canada’s “Track 2” specifically, it upsets me to see logic marshalled to such a stunning end, such that a person — legally quite close to any person — cannot be denied the right to be killed under the auspices of medical care. We all have the right to die, intrinsically. You can exercise that right anytime; it is the one eventuality the government has no possible authority over. It’s somewhat bizarre that only those who cannot seek that end for themselves, the noncommunicative on permanent life support, are barred from a legal medical death — both in Canada and the United States. But let’s be blunt here: For the rest of us, saying no to life is always an option; that’s what makes the routine daily “yes” so powerful.

Ultimately, what upsets me most about this issue is the lethal power in the banalities. Claude Labelle, a disabled man who developed a painful bedsore while visiting the ER in Quebec (whose death rate through MAID is 7.3%), had an easier time asking the hospital to kill him than asking it to provide him with adequate comfort. “I had made my peace with being disabled, with being in a wheelchair the rest of my life, but not in a hospital bed,” Labelle said after changing his mind. You cannot look these stories in the face and wave them away as mere anecdotes from the “vast minority” of cases. They are the exceptions that prove the rule.

Easing a prolonged and painful passing is one thing — it is something I can support, and Canada’s medical assistance in dying certainly provides for it. But it also provides those who have (or should have) other treatment options with what is simply the state-provided right to be killed. That this can then be called “medical care,” in place of all the potential care not offered, is stunningly perverse — it is madness by another name.

Take the survey: What groups do you think should have access to physician-assisted suicide? Let us know.

Disagree? That's okay. My opinion is just one of many. Write in and let us know why, and we'll consider publishing your feedback.

Your questions, answered.

Q: You did a piece about gerrymandering where you said that “gerrymandering is one of the top three most critical political issues in America.” I’m just curious — what other two issues do you think are the most critical?

— Evers from Ann Arbor, MI

Isaac Saul, Executive Editor: I’ll be honest: This is a really tough one to answer. Once you made me think about it, I realized that gerrymandering might be my #1 issue, just because so many other problems are downstream from it. After all, how can we mold the country toward the will of the people if we can’t even elect our own members of Congress in a fair and representative way?

But, the problem of unfair representation is bigger than just gerrymandering. I probably have to put it in an “election reform” bucket (along with open primaries, ranked-choice voting, and voter ID laws), and then altogether that would be my clear cut #1. Then I’d put immigration and affordable housing as my #2 and #3 issues.

Immigration has obviously penetrated the national debate for decades now. The solutions for the border (including mine) are not simple, and that is just one half of the equation. We also have to continue to improve our legal immigration system, which allows families to stay together (my best friend just married a woman from Indonesia, and it’s remarkable how hard it is to get her a U.S. visa) and allows us to attract talent (birth rates are collapsing everywhere, and we should want immigrants who will come here for various jobs, to start businesses, to enrich our society, or to get educated).

At the same time, we have to navigate the ways too much immigration can tear at our social fabric, backseat services and jobs for American-born citizens, or overwhelm the systems we have in place. It’s a delicate line to walk.

Affordable housing as #3 is more a personal preference than anything. Healthcare could just as easily go here, but housing is a much bigger cost for me personally and seems much more solvable in the near term. Having rent you can’t afford or being unable to buy a home makes everything else (child care, health insurance, getting a car, a couple vacations a year, etc.) feel unaffordable too.

Want to have a question answered in the newsletter? You can reply to this email (it goes straight to our inbox) or fill out this form.

Under the radar.

On Monday, a top official with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that approximately 850,000 Syrian refugees have returned to their homes since the fall of former President Bashar Assad’s government in December. The Syrian civil war began in 2011 and created over five million refugees while displacing half of the country’s pre-war population of 23 million. Now, however, the UN says the return numbers are “exceptionally high” following Assad’s removal, and the number of returned refugees could surpass one million in the coming weeks. The Associated Press has the story.

Why Water Alone Isn't Hydrating You

If you're drinking water but still feeling tired, foggy, or crampy, you might be missing key electrolytes.

NativePath Hydrate is a doctor-formulated electrolyte mix that restores cellular hydration fast—without sugar, dyes, or sketchy additives.

Thousands are using it to feel more focused and energized within minutes.

Numbers.

- 1 in 20. The approximate proportion of deaths in Canada that were physician-assisted in 2023.

- 77. The approximate median age of this group.

- 96%. The percentage of patients in this group whose deaths were determined to be “reasonably foreseeable.”

- 52%. The percentage of Americans who supported allowing patients to end their own lives with the aid of a physician in a 1996 Gallup poll.

- 66%. The percentage of Americans who supported allowing patients to end their own lives with the aid of a physician in a 2024 Gallup poll.

- 49% and 40%. The percentage of Americans who said they believe physician-assisted suicide is morally acceptable and morally wrong, respectively, in 2001.

- 53% and 40%. The percentage of Americans who said they believe physician-assisted suicide is morally acceptable and morally wrong, respectively, in 2024.

The extras.

- One year ago today we wrote about the Harris–Walz CNN interview.

- The most clicked link in yesterday’s newsletter was the pumpkin spice latte’s autumnal rival, the maple latte.

- Nothing to do with politics: South Florida is fighting Burmese pythons with robot rabbits.

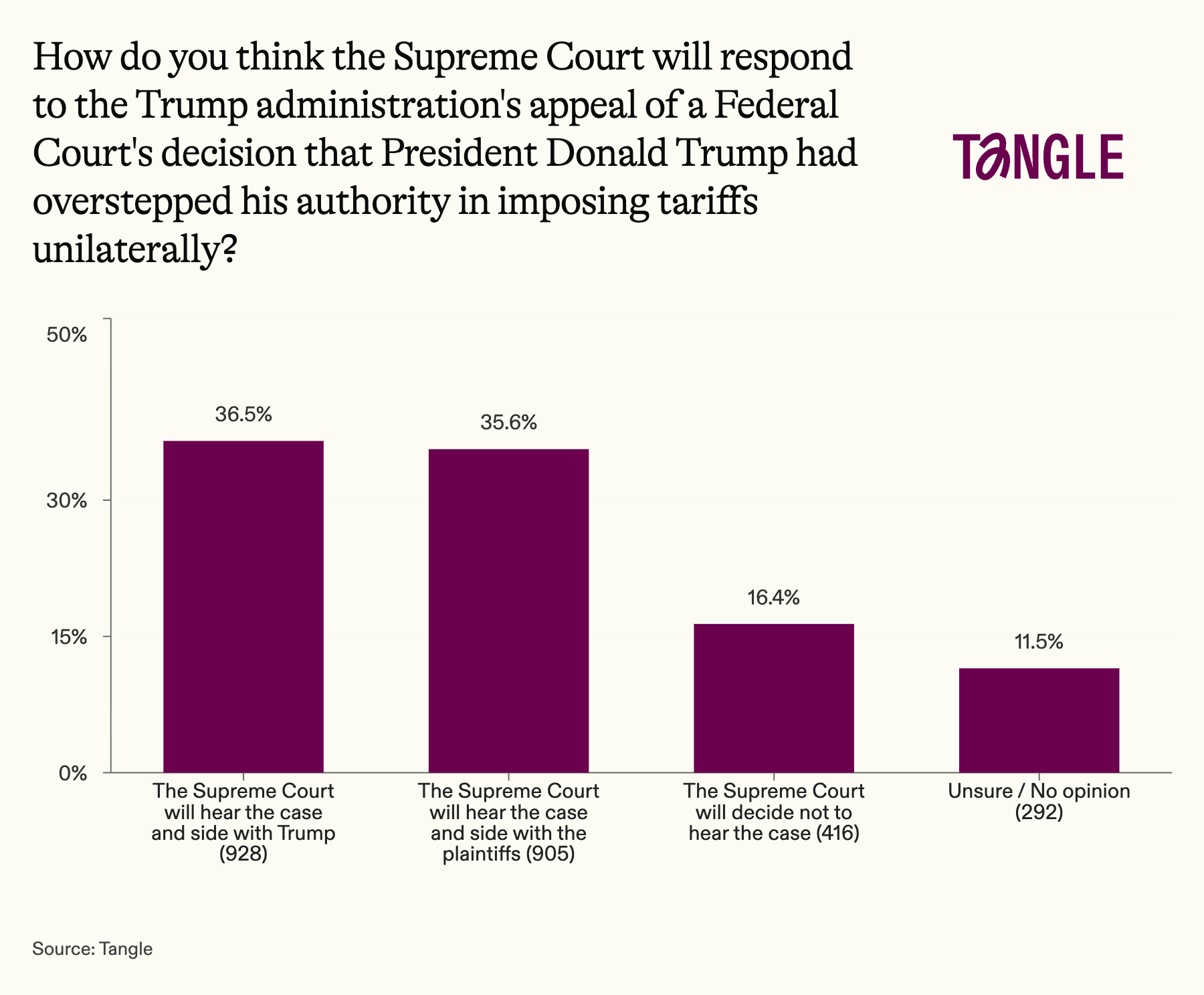

- Yesterday’s survey: 2,541 readers responded to our survey on the federal tariffs ruling with 37% saying the Supreme Court will hear an appeal and side with Trump. “I think the Supreme Court will render some muddled decision that will sort of favor Trump and keep them out of hot water,” one respondent said.

Have a nice day.

When a young boy was seen walking alone along an elevated monorail at Hersheypark in Hershey, PA, a man in the crowd jumped into action. John Sampson, a veterinarian and father of three from Bucks County, PA, climbed on top of the roof of a building adjacent to the monorail, then onto the monorail itself, engaging with the boy before eventually carrying him to safety. The child had been reported missing after becoming separated from his parents, and he was reunited with them after the incident. “I just think I'm a guy who [was in the] right place, right time, saw a child in need and wanted to help,” Sampson said. 6ABC has the story.

Don’t forget...

🎧 We have a podcast you can listen to here.

💵 If you like our newsletter, drop some love in our tip jar.

Member comments