Plus, should statues of Jefferson and Washington come down?

Tangle is an independent, ad-free, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that’s dedicated to helping you better understand what both sides of the political aisle are saying about the news of the day. If someone sent you this email, they’re asking you to support this kind of news by becoming a subscriber. You can try it for free.

Today’s read: 13 minutes.

The most words in any Tangle edition yet: I cover the argument over sending kids back to school, whether Thomas Jefferson and George Washington statues should come down and some important quick hits.

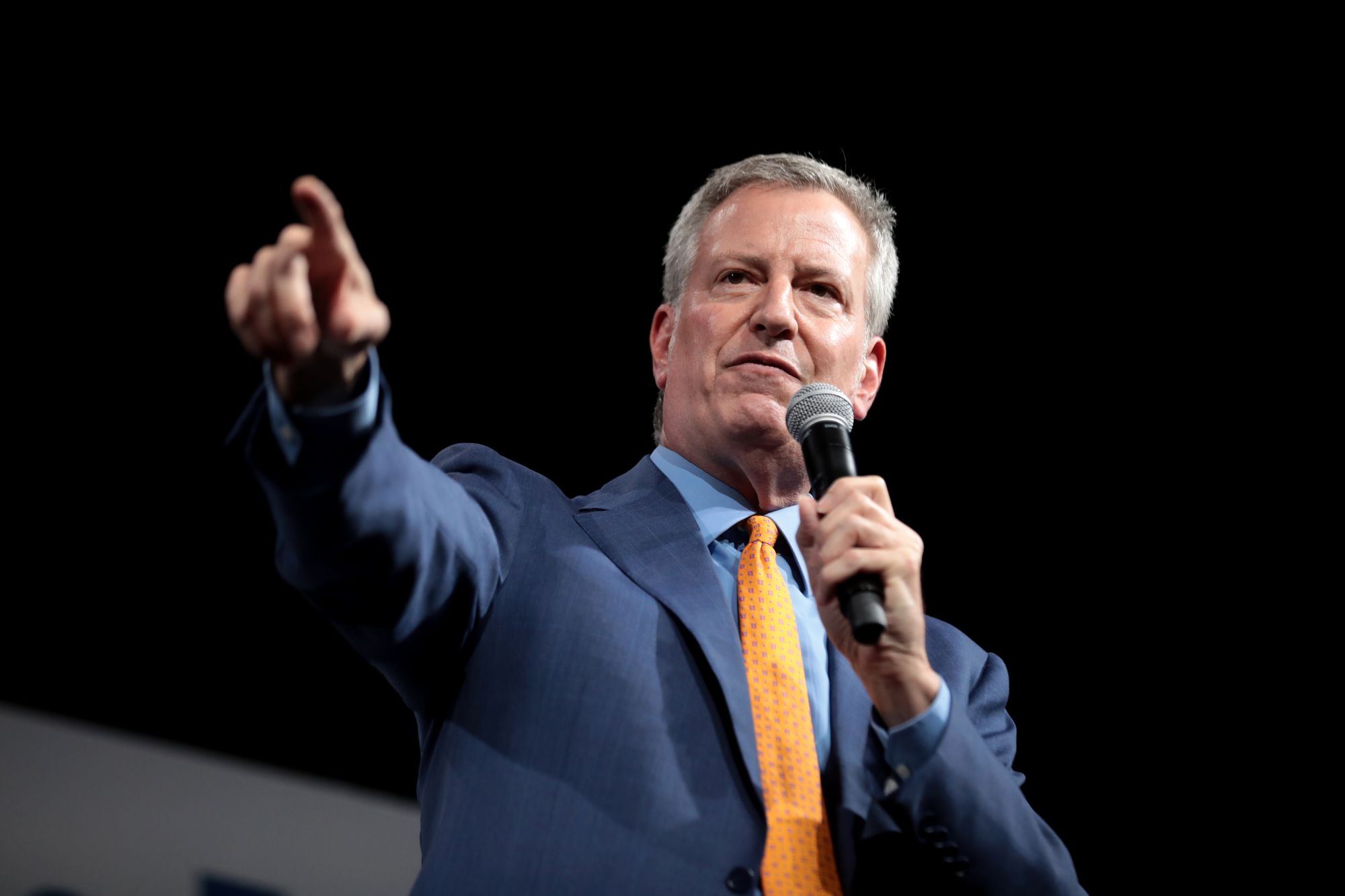

New York Mayor Bill de Blasio announced today that city school will reopen with staggered schedule and part-time remote learning in September. Photo: Gage Skidmore

Reader feedback.

Karen, an Academic Dean from Brooklyn, wrote in with the following just now about yesterday’s issue: “Just wanted to send you a quick response to your info on the non-immigrant visa status for students. A lot of the media articles and posts are painting this as a college thing, but it isn’t just college. I oversee the international students at my 6-12 grade school and all of them are affected by this if we are fully remote in the Fall.”

Quick hits

- The White House officially withdrew from the World Health Organization yesterday, giving a one year notice that we’d break ties with the group by July 6th of 2021. The United States contributes $400 million a year to WHO, making us the largest contributor on the planet, and opponents of the move say withdrawal will damage the organization as it tries to fight an unprecedented global pandemic. Supporters say the move is an appropriate response to WHO’s failures early on.

- Details of the tell-all book written by Mary Trump, President Trump’s niece, leaked to the press yesterday. Mary claims that Trump paid someone to take his SATs, went to the movies the night his brother (and her dad) died in the hospital, and that she believes he’s a “sociopath” (Mary is a clinical psychologist). The book also details how she gave The New York Times the source material that led to a 14,000-word investigation on the Trump family’s dubious tax schemes and fraud.

- Harvard and MIT sued the Trump administration for a new guidance that aims to force foreign students out of the U.S. if their classes aren’t being held on campus. But “visa requirements for students have always been strict and coming to the US to take online-only courses has been prohibited,” CNN reported. The lawsuit argues that the guidance violates the Administrative Procedures Act, which requires the federal government to give reasoning and public disclosure of such decisions.

- More than 150 writers, academics and free speech advocates signed an essay in Harper’s Magazine yesterday arguing that “stifled free speech is creating an ‘intolerant climate’ within society.” The letter celebrates recent progress made on criminal justice reform and the fight against systemic racism, but cautions that activists and protest movements have weakened “our norms of open debate and toleration of differences in favor of ideological conformity.”

- New Jersey announced it will now require face coverings while outdoors, a significant escalation in an effort to stymie COVID-19. Mask requirements for indoor activities like dining have already been fought tooth and nail across the country, despite the advice of epidemiologists. “They've been strongly recommended out-of-doors,” Gov. Phil Murphy said. “We're going to turn that up a notch today and say we're going to ask you if you can't socially distance, it's going to be required.”

What D.C. is talking about.

It’s July 8th. Along with careening towards the middle of the summer, that also means we’re just a month away from the back-to-school season. This year, though, going back to school is no guarantee. COVID-19 cases are rising across the U.S., and in many states where we saw a surge of cases we are now seeing a spike in hospitalizations and deaths. Some college campuses have already announced fully remote classes in the fall, or a mix of online and in-person classes. Others seem to be waiting to see how things will play out. But the bigger, tougher question is not about college education: it’s about K-12 schools.

What we know about COVID-19 is that the virus is much more likely to spread indoors amongst people who spend extended periods of time together — which makes K-12 schools sound like especially dangerous places to be. The difference between K-12 and college students, though, is that those 50 million K-12 kids in public school are then coming home to their parents and — potentially — grandparents, aunts and uncles. And that’s to say nothing of the teachers and staff, many of whom are middle-aged or elderly, who will need to be present in school for classes to go on.

At the same time, it appears that kids are less at risk of contracting the virus and coming down with serious cases (though it’s certainly not unheard of). The question of how efficiently they can spread the virus has proven much harder to answer. This paradigm has set off a debate across the political and childcare spectrum. Sending kids back to school is more than just a question of our children’s education. It also has serious economic, political and health care ramifications.

Without school, as cities like New York have been learning since March, kids need childcare. Today, New York City announced it would send kids back in September on a staggered schedule with more remote learning, with the 1.1 million public school students attending class in person two or three days a week. That means parents need to spend money, stay home, or find a place for their kids to spend the day. Without school, many low-income parents also lose an important resource. Schools provide meals, social work and even medical attention for parents in need. Losing in-school classes would further deepen the socioeconomic divides that already exist across the country.

It’s not just the U.S. facing this problem, either. Schools have closed in 191 countries, impacting over 1.5 billion students and 63 million teachers, according to the United Nations. Some schools are now reopening in New Zealand, China, Germany, Denmark and Vietnam. But those places have something the U.S. does not: the virus is receding by almost every measure and contact tracing systems are closely tracking hotspots where it pops up.

What the right is saying.

The right seems a little more unified in the “get back to school” stance. President Trump urged schools to reopen “quickly and beautifully” yesterday, saying he planned to put pressure on governors to open the schools and get classes going in the fall. The American Academy of Pediatrics seemed to agree with the president, releasing a letter and guidance in late June on getting kids back to school. AAP harped on the differences in how COVID-19 impacts children and adolescents but also on the costs of keeping schools closed.

“Schools are fundamental to child and adolescent development and well-being and provide our children and adolescents with academic instruction, social and emotional skills, safety, reliable nutrition, physical/speech and mental health therapy, and opportunities for physical activity, among other benefits,” it wrote. “Beyond supporting the educational development of children and adolescents, schools play a critical role in addressing racial and social inequity.”

The Washington Examiner editorial board published a piece that leaned heavily on the AAP’s letter, calling for K-12 school reopenings in the fall.

“Importantly, at a time when political extremists ridiculously scream ‘racism!’ at anyone who just wants to end lockdowns, AAP points out the significant and disparate racial effect of school closures,” the board wrote. “For wealthier suburban communities that happen to be mostly white, a school closure is an annoyance. For poorer neighborhoods where the children are more dependent on schools for daily meals, social work, and medical attention, these closures can be far more serious and disruptive.”

Spencer Bokat-Lindell went a step further in The New York Times, where he examined both sides of this issue. Bokat-Lindell noted that, as of June 30th, only about a dozen of the 126,000 Americans who have died of coronavirus were between the ages of 5 and 14. That’s far fewer than the 1,700 who die of abuse and neglect every year — afflictions teachers are often the first to see and intervene in. It’s just another example of the untold cost of leaving kids at home and the price they pay for not having school.

In the Wall Street Journal, one important calculation leaned on the efficacy of remote learning: “This spring, America took an involuntary crash course in remote learning,” The Wall Street Journal reported. “With the school year now winding down, the grade from students, teachers, parents and administrators is already in: It was a failure.”

What the left is saying.

The left is completely split. Many on the left have made identical arguments to the Washington Examiner about the cost of keeping schools closed, including The New York Times editorial board. In April, the board noted that “The learning setbacks that schoolchildren commonly experience over a summer vacation can easily wipe out one or two months of academic growth,” which means that the COVID-19 setbacks 50 million children are experiencing now “could well be catastrophic by comparison.”

Much of the left’s concern is not about the kids so much as it’s about the other people inside the school. In March in New York City, the largest public school system in the country, it was teacher unions and teacher organizations that had to pressure Mayor Bill de Blasio into closing the schools down.

“There are about 3.2 million public-school teachers nationwide, and an untold number of aides, administrators, food-service workers, custodians, guards, and school-bus drivers,” Amy Davidson Sorkin wrote in The New Yorker. “Will every at-risk teacher be furloughed or put on disability? Simply marginalizing vulnerable staff members is not a solution.”

MIT Technology Review recently published a wide-ranging piece on the risks faced by children and teachers. It projected confidence that K-12 kids are less likely to get the virus, less likely to get seriously ill and that the mysterious inflammatory syndrome that panicked parents nationally a few months ago has proven to be exceptionally rare (there are about 500 known cases of it globally). But the question of whether kids can easily spread the virus is still unknown.

“If you look at the peer-reviewed literature, it’s very mixed,” Jeffrey Shaman, an infectious disease expert at Columbia University, said. “The simple answer is we don’t know.” We do know it’s possible, though, as a study from China “identified three occasions when a child under 10 was the ‘index case’ in a home.”

Meanwhile, writers from Vox have been beating a different drum. Matthew Yglesias and German Lopez have each published separate pieces urging states to close bars and restaurants while reopening schools. Lopez argued that schools are the most important thing to have up and running in a community, but reopening them is not about finding safer guidelines for indoor interaction (though that’s, of course, crucial). Instead, he argued, “Whether a school can reopen safely… depends on how widespread the coronavirus is in the community outside the school’s walls.”

In other words: reopening is about having a safe community with limited presence of the virus. That means sacrificing or adjusting other super spreaders — like bars and restaurants — in order to send kids back to school.

My take.

First, I want to acknowledge the Libertarian argument here, which didn’t fit neatly above but I thought was also important. Robby Soave wrote in Reason that schools shouldn’t just open, they have an obligation to, since we’re all still paying for them with our taxes.

“It’s hardly fair for the state to confiscate vast sums of money from its citizens, in part for the purpose of child care, and then suddenly cease offering this service while keeping the money,” he wrote. “States that want to make it possible for people to return to work — for the economy to reopen — really need to prioritize schools: They are among the first elements of public life that must return to a semblance of normality, and the risks seem comparatively low.”

Soave’s argument is likely to resonate more with the right than the left, but it’s a strong point about the order of operations — and actually fits neatly with the lefty Vox writers who advocate prioritizing schools.

I don’t envy any public official, state, city or town trying to navigate this. And I don’t have an answer, either. As a politics reporter, most days I’m writing Tangle I feel I’m operating in my wheelhouse, with a baseline of expertise or knowledge on U.S. history and current events that helps me understand the arguments I’m reading better than the average person. But I’m not a parent. I’m not a teacher. And I’m not an epidemiologist.

There do seem to be a few things clear to me in these arguments, though, from both sides, so I’d like to suss them out:

1) When it comes to the kids alone, the costs and risks of keeping schools closed seem far higher than the costs and risks of reopening them. The learning drop-off would be profound and could handicap an entire generation. 12 million kids didn’t have the internet access they needed to do online learning this past spring. Studies on virtual charter schools indicate they are no match for in person learning, and — even (perhaps especially) from the health care perspective — the AAP stresses that “school is an important bulwark against hunger, social isolation, physical and sexual abuse, drug use, depression and suicidal ideation.”

2) The teachers and staff who make schools run will be at serious risk. There needs to be a program to support those people, should they not be able to come back to school this fall. Outside the U.S., in Denmark, Australia, Taiwan and other countries, students were sent back to school with masks, temperature checks and desks spaced 6 feet apart. These protocols seemed to mitigate risk for everyone, but it means our schools won’t look the way we’re used to them looking. And even with precautions, countries like Israel and China have had to close down some schools already in response to outbreaks.

3) We’re in a uniquely bad position because of how badly the virus is still spreading. All these other countries we want to model have significantly reduced their cases, and most are trending in the right direction, while we’ve done the opposite. The U.S. is setting daily records for new cases as we speak, in a summer that many were hoping would be a reprieve from the virus. The arguments made by the Vox writers were very compelling: the first step to opening schools is prioritizing them over everything else so community spread is limited. Without that, all the precautions in the world won’t keep the virus out.

If there is a takeaway here, I think it’s that we need to be planning to reopen now. Why not? What’s the cost? If every state, city and town is drafting plans to get kids back to school, soliciting feedback from its citizens, teachers and parents, then at least there is a hope of bringing kids back in September. It’ll be a lot easier to delay the openings to address outbreaks than it will be to draft a plan in late August to get things up and running if it’s safe. We should be planning for the best and hoping we never see the worst.

Your questions, answered.

Reminder: every day, I answer a reader question from across the country. If you have a question — or feedback — you can reach me by just replying to this email. It goes straight to my inbox.

Q: A few weeks ago, you wrote that you approved of moves to rename bases named after Confederate soldiers and you seemed to generally support the removal of Confederate monuments. Now that protesters are pushing to remove statues of Thomas Jefferson or George Washington, where do you stand?

— Tim, Paxton, Nebraska

Tangle: The statue issue seems to be getting stickier by the day. When I addressed this a month ago, the question was mainly centered around Confederate monuments and the military bases named after Confederate soldiers. I compared the two sides’ arguments, and then wrote this in the “My take” section:

Being Jewish, I also consider how similar monuments might impact my own psyche. I won’t dive into the absurdity of comparing General Lee to Hitler, but I imagine if I had to walk by a statue or hear about a military base venerating a leader who lost a great battle aimed at keeping the Jews enslaved and preventing the development of a unified Jewish democracy, it’d be pretty upsetting. Yes, the Civil War was more complex than just a battle over slavery. But the contours of this historical time are obvious and pronounced to anyone willing to look at them.

In a similar way, I’m sympathetic to the people — both white and people of color — who are calling for monuments of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson to come down. As Charles Blow recently wrote in The Times, Washington was “an enslaver who signed a fugitive slave act and only freed his slaves in his will, after he was dead and no longer had earthly use for them.” Jefferson “enslaved over 600 human beings during his life” and “had sex with a child whom he enslaved — I call it rape — and even enslaved the children she bore for him.”

At the same time, as I discussed in a recent email exchange with a reader, these men cannot be defined simply by the atrocities of slavery. It’s an indelible mark on their character and being, and it’s something that should be taught in every history class in every school. But it’s not the totality of who they were. The most simple and obvious example is that Washington and Jefferson owned slaves while authoring writings, laws and ideals that simultaneously entrenched racial inequality in our country and also helped lead to the end of slavery and the concept of equality our nation still strives to today. As usual, history is nuanced and tangled.

You might also consider how this argument has evolved. In 2017, after the Charlottesville protests, a Robert E. Lee statue was torn down. President Trump asked incredulously at the time: “So this week it’s Robert E. Lee. I noticed that Stonewall Jackson is coming down. I wonder, is it George Washington next week? And is it Thomas Jefferson the week after? You know, you really do have to ask yourself, where does it stop?”

At the time, his comments were met with derision. Professors of history and liberals scoffed at the idea that the American public couldn’t decipher the difference between Confederate soldiers who fought to preserve slavery and presidents who owned slaves. Shortly after Trump’s comments, Princeton professor David A. Bell wrote this about considering Washington in a 2017 piece (emphasis mine):

In the case of Washington, it involves weighing his role as a slave owner against his role as a heroic commander in chief, as an immensely popular political leader who resisted the temptation to become anything more than a republican chief executive, and who brought the country together around the new Constitution. [Vice President] Calhoun, by contrast, devoted his political career above all to the defense of slavery. The distinction between the two is not difficult to make… Lee’s case is clear-cut. Whatever admirable personal qualities he may have had, he was also a man who took up arms against his country in defense of an evil institution. In my view, he doesn’t deserve to be honored in any fashion.

And yet today, Trump seems prescient. A debate about the Washington and Jefferson memorials is raging, and two such statues have already been torn down.

“Conservatives warning about the dire consequences of some social change are dismissed as hysterical cranks — and then, when exactly what they predicted eventually comes to pass, denounced as bigots for opposing the new order,” Megan McArdle argued in The Washington Post.

U.S. history is whole lot of grey. It is not black and white. I reject arguments that Jefferson and Washington were unambiguously evil men — but at the same time understand that they were not the moral North Stars many Americans imagine them to be. Anyone who has studied U.S. history for any length of time knows that the debates over slavery, over conquering The New World, over race, over equality, were generated by robust disagreements and — as the Civil War demonstrates — often settled through violent conflict. Many political leaders were vocally opposed to slavery, even while Jefferson and Washington were alive (this, of course, does not help their case).

I recently pointed out to some friends (and on Twitter) that Columbus landed in Hispaniola in 1492, and the Declaration of Independence came in 1776. That’s 284 years. It’s been just 244 years from the Declaration of Independence to today, 2020. In other words: more time and more history elapsed between Columbus’s arrival in The New World and the signing of the Declaration of Independence than between the signing of the Declaration of Independence and today.

Those 284 years were not as simple as a bunch of white conquerors deciding to slaughter and rule a new world. They were rife with conflict, self-doubt, struggles and illusions of a moral superiority. The English thought the Spanish were brutes. The Spanish thought the natives were savages. By the time George Washington (1789) and Thomas Jefferson (1801) became the first and third presidents of the United States, the evil side of these debates was firmly in control of setting the ethical and moral standards we lived by. We had, in fact, slaughtered and killed (intentionally through battle or accidentally via disease) millions of Natives. We were shipping in slaves to harvest the fields under the preposterous idea that God wanted us to cultivate the land and people with darker skin were somehow less than the white man.

All of that is historical fact — but it was by no means a simple or black and white evolution to get there. And Washington and Jefferson were not unbending or absent of conflict in how they lived.

All this is to say the moral and ethical standards or framing of Jefferson and Washington should be honest and complete, unlike how they were when I was in school. They are not solely defined by the fact they were great leaders, nor should they be solely defined by the fact they held slaves. If measured by the atrocity of slavery alone, one can’t reasonably make an argument that Washington and Jefferson were operating on similar moral grounds themselves: Jefferson’s crimes were far worse.

Does that mean that their statues should be removed or torn down? The threat may be a bit exaggerated. 150 statues and memorials nationwide have been torn down by protesters, and just three of them targeted former presidents — George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Ulysses S. Grant. The rest were almost exclusively Confederate monuments, save a few embarrassing mistakes. The culture war has made this seem like a far bigger deal than it actually is.

Acknowledging all this, what I do feel confident saying is that if we are going to remove statues of former presidents, they shouldn’t be removed by a mob. That’s just a line I don’t feel comfortable crossing. We have mechanisms for this kind of thing — like raising a petition in your town to take down a statue or pushing a ballot measure to remove a monument — that are far more democratic, efficient and fair than an angry group of people tying a rope around a statue and toppling it. If a petition to remove a Jefferson or Washington statue ever landed on my door, it’s unlikely I’d support it. But it’d certainly give me pause.

A story that matters.

COVID-19 is going to undermine trust in government for years to come and simultaneously make people less likely to resume their previous spending and investment patterns, a pair of new research papers say. Together, “the studies bolster a view increasingly voiced by experts: there may never be a ‘return to normal,’” The Washington Post reports. The first paper finds that COVID-19 is likely to cause a persistent fear about the probability of an extreme shock to the economy. The second paper, which studied trust in institutions across countries that experienced pandemics, found that “an individual with the highest exposure to an epidemic (relative to zero exposure) is 7.2 percentage points less likely to have confidence in the honesty of elections; 5.1 percentage points less likely to have confidence in the national government; and 6.2 percentage points less likely to approve the performance of the political leader.” Click.

Numbers.

- 7. The number of corrections I said I had issued in the Tangle newsletter during a correction notice in yesterday’s newsletter.

- 8. The number of corrections I have actually issued in Tangle newsletters, as a few eagle-eyed readers pointed out.

- $2 billion. The amount that the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Defense have invested in coronavirus research.

- $11 million. The amount that companies linked to lawmakers and congressional caucuses have received from the Paycheck Protection Program.

- 7%. Democrat Mark Kelly’s lead over Republican incumbent Martha McSally in Arizona’s Senate election.

- 61%. The percent of voters who said they would be more likely to support Senate candidates who support background checks.

- 10%. The percent of voters who said they would be more likely to support Senate candidates who oppose background checks.

6,000.

Tangle is closing in on 6,000 free subscribers (just 33 away!). As I often say, this newsletter is a grassroots effort to improve political discourse, understanding and journalism in our country — and I lean heavily on readers to help me spread the word. Please consider helping me push past the 6,000 landmark by forwarding this email to friends or posting about it on social media. You can share the about page or press the button below, and remember: anyone can try it for free.

/about

Have a nice day.

A “healing Jazz porch” in Brooklyn, New York, is helping the city weather the coronavirus pandemic. For nearly three months straight, every day, a group of professional and amateur musicians have made their way to a porch in Brooklyn’s Flatbush neighborhood to put on a performance for anyone who happens to pass by. Some days, the performance draws a large crowd of mask-wearing, social-distancing New Yorkers who can unwind and dance along to quality music. The jam sessions are being led by Roy Nathanson, a 69-year-old professional saxophone player. Click.