There are plenty of potential solutions available.

I’m Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, ad-free, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum on the news of the day — then “my take.”

First time reading? Sign up here.

Setting the table.

Few things draw as much scrutiny from the public as gerrymandering.

In the last few decades, the practice of congressional map drawing has become such a precise science that outcomes in future elections can be predetermined and predicted with surprising accuracy based solely on how a district is drawn. This reality has created pre-election fights that can have outsized impacts on who will control the most important levers of politics at the local, state and congressional levels.

Over the last two and a half years of writing Tangle, few topics have been requested as often by readers as this one. Despite being such a frequently talked about political issue, gerrymandering remains a difficult topic to cover from the national perspective. Every time maps are redrawn, they have specific and significant impacts on voters at the local level, with a huge range of variance across the country. All this is to say, as always, today's issue is not all-encompassing. It'd be impossible to cover everything on this topic in one newsletter.

However, what we are going to try to do is deliver a brief history of gerrymandering, break down the current state of play heading into 2022, share some recent commentary about this issue, float some potential solutions, and then — as always — I'll share some of my own personal thoughts.

Finally, it's also worth noting that today's focus will be on redistricting and gerrymandering that impacts Congress. Though it should be said explicitly — and will be alluded to in places — that gerrymandering has an impact on state and local elections, too.

The history.

Gerrymandering has been around for a long time. Long enough, in fact, that most of us don't even pronounce it the way the folks who named it intended us to.

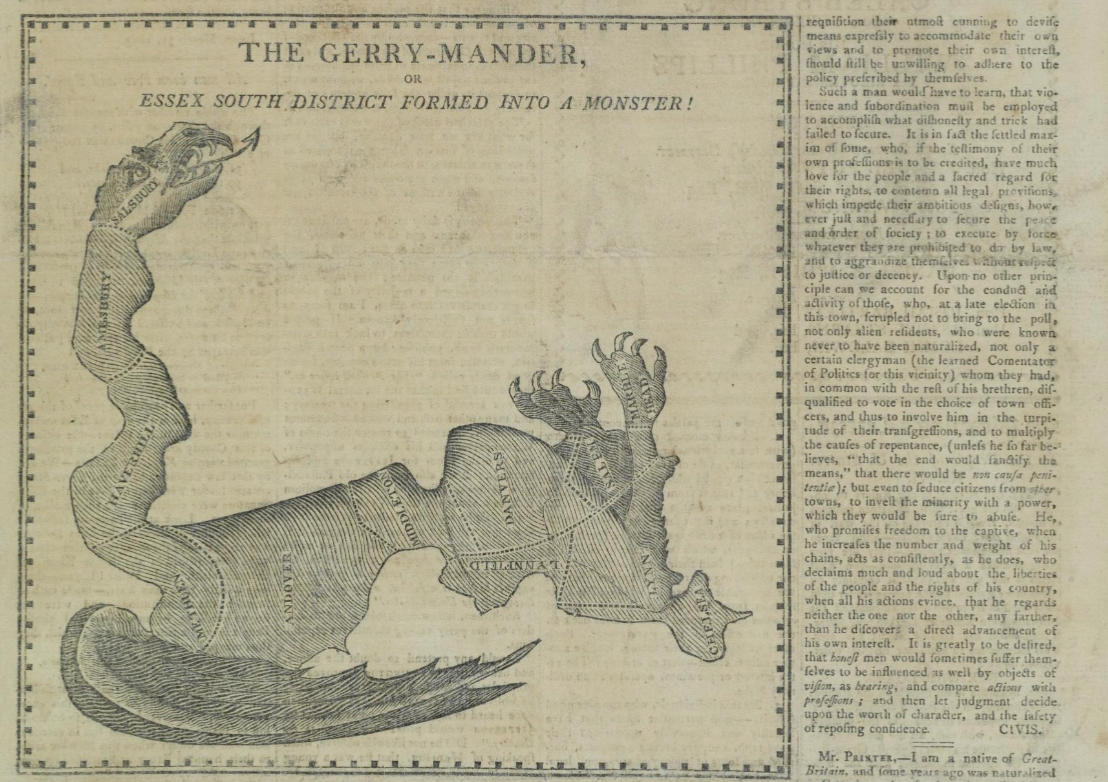

The term gerrymander was born in a Boston Gazette cartoon from 1812, which depicted a "new species" of monster: The Gerry-mander. The cartoon depicted a creature shaped like a Massachusetts voting district that had been drawn by the state's Jeffersonian Republican party and signed by Gov. Elbridge Gerry (pronounced "Gary"). Since then, the practice has been known as gerrymandering (pronounced Jerry-mandering), though back then it was surely pronounced Gary-mandering. While Gov. Gerry would go on to become vice president, he's been cemented as the namesake of a political practice that bends — and sometimes breaks — the rules of fair elections.

Gov. Gerry may own the name, but he certainly didn't invent the practice. It goes all the way back to 18th century England and "rotten boroughs," and has continued into the present day.

To understand gerrymandering you first have to understand the rules that create the opportunity to do it. State legislatures are required to redraw congressional districts every 10 years in response to the latest Census data. Thanks to a Supreme Court ruling in the 1960s, these districts must be roughly equal in population in order to ensure a balanced representation in Congress. However, because state legislatures are often controlled by one party, they regularly attempt to draw these districts to give their counterparts in the federal government — in Congress — an advantage. The Week gives a simple example: "The party in power can take a district in which the opposition draws 50 percent of the vote and divide it in two, ensuring the minority party will lose both districts."

In the post-Civil War era, the practice of drawing districts to exclude certain voters became far more common, as southern states regularly did their best to exclude Black voters that had recently joined the electorate. This is when we first started seeing thin, winding tentacle-like districts that were clearly wrapping around certain populations to avoid or isolate them. Concentrating as many Black voters into one district would ensure safe white majorities in the others. Today, many onlookers still believe "partisan" gerrymandering is always about race.

From the early 1900s until the 1960s, there was actually very little gerrymandering. A few things were at play here: For starters, different intimidation tactics like lynchings and poll taxes, which effectively kept many Black voters from casting ballots, were being widely practiced. Minority Americans were also moving into the cities, and politicians on both sides of the aisle seemed largely content to let those demographic shifts play out. But in the 1960s, the "redistricting revolution" began.

It was driven, in large part, by a series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions. History.com has a great, brief summation of this time period:

The U.S. Supreme Court changed this in the 1960s with a series of court decisions known as the “redistricting revolution.” Under Chief Justice Earl Warren, the court ruled that all state voting districts must have roughly equal populations. In addition, states must adjust their federal congressional districts after every 10-year census so that each of the 435 members in the U.S. House of Representatives represents roughly the same number of people.

Combined with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which protected Black Americans’ right to vote, these Supreme Court decisions ensured voters were more evenly represented in their state legislatures and the U.S. House of Representatives. (The court singled out the U.S. Senate as a unique institution whose members didn’t need to represent the same number of people.)

What ultimately led to the biggest change in gerrymandering was a non-political revolution: computers. In the 1990s, with access to reams of data and the ability to complete complex calculations at scale, political parties began drawing districts with the kind of precision they never had been able to before. This meant, in general terms, that the political parties were now picking the groups of voters they wanted to determine the outcome of elections.

While both Republicans and Democrats heavily gerrymander in states where they control the legislature, Republicans have been far more successful at gaining outsized representation over the last few decades. They've also been sued repeatedly under the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits gerrymandering designed to water down the influence of minority voters. In 2017, a North Carolina map was struck down by the court.

In 2019, however, the Supreme Court ruled that regulating partisan gerrymandering was beyond the purview of the federal courts. That will leave the decisions on which maps stand and which will fall largely in the hands of state Supreme Courts, who often have the same partisan makeup as their counterparts in the state legislature. This has a lot of people wondering what the maps will look like this year, following the delayed 2020 census counts.

The present day.

You might remember a few months ago when we ran an issue on the results of the census. This is the data that Congress uses to help draw these districts, and it's this simple act of counting who lives in the U.S. and where they are that has become so important politically. In the latest census, Colorado, Florida, Montana, North Carolina, and Oregon all gained one seat in Congress. Texas gained two. Meanwhile, California, Illinois, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia all lost one seat.

Four of the six states that gained seats due to their population growth voted for Trump in 2020 and 2016, and are controlled by Republican state legislators: Texas, Florida, Montana and North Carolina.

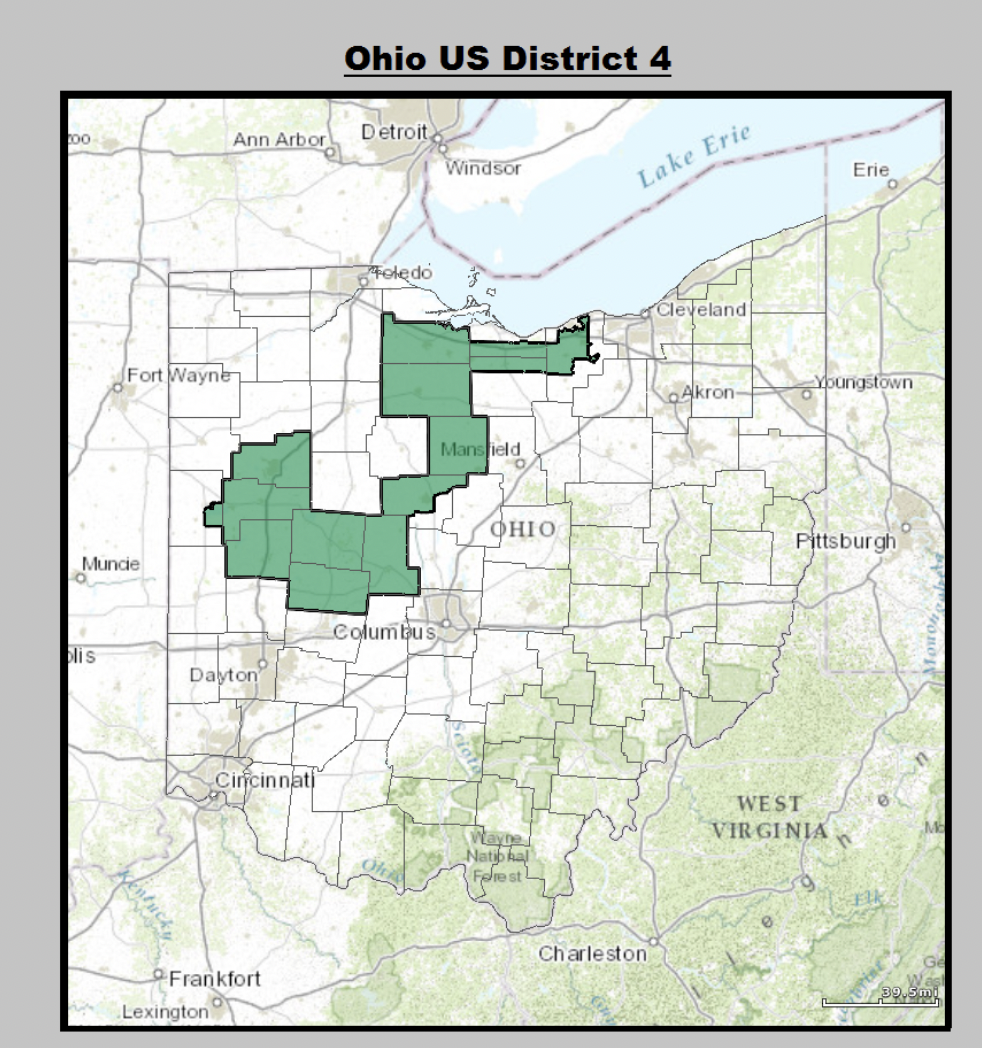

This new year of district-drawing has already been rife with controversy. A panel of North Carolina judges just upheld a GOP-drawn map that will strongly favor Republicans and have an outsized impact on 2022, though Democrats will certainly appeal (and, with a Democratic majority on the state Supreme Court, may get it overturned). In Ohio, meanwhile, the state Supreme Court just shot down a gerrymandered map for the state legislature, which means they'll almost certainly apply the same standard to Ohio's congressional map and shoot that down, too.

In striking down OH's legislative maps, the court's majority ordered districts to be as proportional to the state's 54%-46% GOP lean as possible. If the same order applied to congressional, might translate into an 8-7 Trump map (far cry from GOP 11-4 map). https://t.co/fb4873FGt1

— Dave Wasserman (@Redistrict) January 13, 2022

So far, 34 of the 39 states have completed their redrawn House district lines. Cook Political Report, which tracks Congressional races and gerrymandering, has released a report on the districts, and given us an updated state of play. Dave Wasserman, who goes by "Redistrict" online and is considered the authoritative voice on this topic, said the following:

The surprising good news for Democrats: on the current trajectory, there will be a few more Biden-won districts after redistricting than there are now — producing a congressional map slightly less biased in the GOP's favor than the last decade's. The bad news for Democrats: if President Biden's approval ratings are still mired in the low-to-mid 40s in November, that won't be enough to save their razor-thin House majority (currently 221 to 212 seats).

In some ways, the latest on these maps was predictable. Experts like Wasserman have been saying all along that the left's doomsday scenario was never going to come to pass, even though Republicans had the authority to redraw districts for 187 seats compared to the 75 seats Democrats had to work with. That's because many GOP-controlled states are already gerrymandered, and squeezing out any more gains was always going to be difficult.

It's also a matter of strategy. Rather than "go on offense," as Wasserman put, many Republican mapmakers instead battened down the hatches. In Texas, for instance, Republicans were more concerned about keeping incumbents safe than taking over Democratic seats. In states where they did go on offense, like Ohio and North Carolina, court challenges are still being fought.

Democrats, meanwhile, spared little opportunity. They heavily gerrymandered in Illinois, New Mexico and Oregon, and independent commissions drew them surprisingly favorable maps in California, New Jersey and Michigan. In New York, an independent commission failed to agree on a new congressional map, which means the entire process may fall apart and end up back in Democrats’ hands just eight years after voters tried to stop the partisan practice. If that happens, Democratic lawmakers are expected to squeeze every seat possible out of the state in an effort to close the gap in the 2022 midterms, which they are (as of now) predicted to lose. New York could go from a 19D-8R map to a 23D-3R map if they succeed.

With more than a dozen states still completing their maps, it's too early to give a final judgment on who has the "advantage" after this year’s redistricting. But on the current trajectory, Democrats will actually gain a few Biden-won seats in Congress, not lose them, so it certainly appears that it won't be the GOP sweep many had expected. Wasserman, always looked to for his wisdom in this space, says "Still a GOP advantage, but redistricting looks like a wash."

It should be noted, of course, that the numbers don't tell the full impact of redistricting. First, there is the impact on the voters: This year, the biggest impact of redistricting will be yet another reduction in competitive congressional races. The number of seats with single-digit separation between Biden and Trump declined from 62 to 46 (a 26% drop, Wasserman noted). "That means a House even less responsive to shifts in public opinion, with more ideological 'cul-de-sac' districts where candidates' only electoral incentive is to play to a primary base," Wasserman wrote.

Given that only 40 of the 435 congressional races were considered competitive in 2016, this is perhaps the central legacy of gerrymandering today.

The other effect to consider is the one on politicians. Rep. Devin Nunes, the California Republican who has been a loyal backer of former President Donald Trump, retired before his term expired this year. His decision was reportedly driven in large part by the expectation that California's nonpartisan redistricting commission was going to "transform the district he has represented for 19 years from a dusty, rural swath that voted for Mr. Trump in 2020 by 5 percentage points into one centered here in Fresno, the fifth-largest city in California, which Biden would have carried handily."

Of course, members of Congress have little interest in running in races they expect to lose, and so when presented with this conundrum they often retire. 26 House Democrats have already announced their plans to vacate their seats this term, including 18 who are going to retire altogether (the other eight are running for different offices). That's the highest number of Democrats to leave their districts since 1996, when 29 stepped down, and the midterms are still nine months away.

The retirements are a sign of pessimism, but they're also — arguably — a much larger reason Democrats are facing such an uphill battle heading in 2022. Incumbent power is strong, and losing it is costly.

Some opinions.

Cook Political Report's latest breakdown of redistricting has brought a whole new wave of commentary on what 2022 looks like and what's ahead.

In The Washington Post, Paul Waldman said there has been a "redistricting turnaround."

"As one analyst after another noted, Republicans control more state legislatures and more redistricting processes, while in many states controlled by Democrats, redistricting is done by independent commissions. As a result, Republicans might be able to win the House through redistricting alone, even without increasing their vote share in the 2022 midterm elections. At least that’s what everyone thought. Until now.

“Just in the past few days, the conventional wisdom on redistricting has undergone a dramatic shift. The most informed redistricting experts now say it appears that this process will look more like a wash, or even that Democrats might gain a few seats. How did this happen? Here are the key factors:

- Republicans had already gerrymandered so aggressively in the post-2010 redistricting that they had limited room to add to their advantage.

- In the relatively small number of states where they had the opportunity, Democrats are gerrymandering with equal vigor.

- In some places, Republicans opted to consolidate their current position rather than take a riskier path that might expand their seats.

- Independent redistricting commissions wound up not hurting Democrats in the way some feared they would."

The Wall Street Journal called it the "end of the GOP gerrymandering panic."

"Count this as another conventional-wisdom implosion," the board said. "The expectation of a lopsided GOP gerrymander in 2022 came partly from the misperception that the adoption of 'independent' redistricting commissions would extinguish Democratic opportunities to make partisan gains," the board said. "But like any other political body, the commissions are subject to influence by interest groups.

"The map released by California’s commission could eliminate three of the 11 GOP seats in the state’s House delegation; Democrats currently hold 42 seats. New Jersey’s commission polarized along partisan lines, with the designated tie-breaker choosing the map that protects most Democratic gains of the past decade. New York’s commission appears to be breaking down, likely handing control to Democrats in Albany, who could cut the number of New York House Republicans to three from eight.

"Colorado’s redistricting commission did blunt potential Democratic gains in the increasingly blue state," the board said. "Conversely, Arizona’s drew a map more forgiving toward Democrats than might have been drawn by the state’s GOP-controlled Legislature. As for states that don’t have redistricting commissions, Illinois, Maryland and Oregon pursued aggressive Democratic gerrymanders. Republicans did the same in Ohio and North Carolina... Far from governing through 'minority rule,' Republicans have won more overall votes in most U.S. House elections since 1994, and they currently lead in generic ballot polls for 2022."

Dan Balz writes that when gerrymandering is "left in the hands of politicians — politicians of either major party — the opportunity to use the process of drawing congressional and legislative district lines for partisan gain is irresistible."

"The current round proves the point," he said. "In states where they have the power to act largely unimpeded, both Republicans and Democrats are practicing the dark art of gerrymandering. 'A number of states are likely to take gerrymandering to pretty farcical extremes,' said David Wasserman of the Cook Political Report with Amy Walter. 'Republicans will gerrymander more than Democrats because they have more power, but because neither Congress nor the Supreme Court has stepped in, it remains this never-ending game of one-upmanship.'

"Republicans have used their power to draw a congressional map in Texas that will continue to keep themselves with a firm grip on the delegation — doing so while ignoring the changing demographics of the state," Balz wrote. "Nearly all the population growth in Texas over the past decade has been from people of color, and because of that growth Texas was given two more congressional seats through reapportionment. But the two new districts appear to put their fate into the hands of White voters, rather than Hispanics.

"When Democrats controlled many more state governments, it was the Democratic Party that used the redistricting process to its advantage," he added. "In the 1980s, Phil Burton, then a powerful California House member, boasted about one mangled district he had helped to engineer, calling it 'my contribution to modern art.'"

The solutions.

As you might expect, there are a lot of theories out there about how to fix gerrymandering. Unfortunately, some of the most-anticipated attempts at reform have stumbled.

Perhaps the most popular is an independent commission. The idea comes in a few different forms but the basics are usually the same: an even split of Republicans and Democrats to collaborate on drawing maps, and perhaps a set of non-partisan or non-ideological members to help settle disputes. 13 states, right now, have independent commissions.

Unfortunately, the results have varied widely. In California, for instance, the independent commission has produced a proposal that would give Democrats 75% of the congressional seats despite owning just 59% of the statewide votes. In New York, the commission is on the verge of imploding, stuck in a total gridlock, and Democrats are preparing as if the process will ultimately fall into their laps.

These, of course, are two examples of the process not going as planned. In other places, it has been rather effective. Virginia's maps are being celebrated as some of the fairest in the country even after their commission ran into partisan gridlock. Sam Wang, the director and founder of the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, said the maps came out successfully because they leaned on the project's algorithmic grading system that looks at competitiveness, geography and partisan fairness.

Virginia's congressional and House of Delegates maps received A grades overall, and the state Senate map received a B. Wang attributed this success to a transparent process that incorporated public feedback, a well-written legal criteria to follow, and a good final backstop mechanism: the state Supreme Court to break any gridlock. Despite concerns about the partisan make-up of the court, Wang says, the legal criteria helped assure a ruling that preserved fair districts.

In Colorado, the commission backed by Democrats produced a map so fair they wondered aloud if they had given up too much power. That's probably a strong endorsement. While independent commissions may be the most popular gerrymander-fighting method, options abound.

Law professor Joshua Douglas, who authored Vote for US: How to Take Back Our Elections and Change the Future of Voting, has said the solution must come from the state courts. Douglas lambasted the Supreme Court for washing its hands of the issue in 2019. "Defying all logic," he wrote, "it said that federal courts cannot provide a legal rule for when partisanship has infected the redistricting process too much. But the Court then suggested that all was not lost, speculating that state law could provide a remedy for the worst abuses."

Douglas understands the cynics who view state legislatures as overtly partisan and wonder how the appointed members of a court could be the solution. But, he says, "state constitutions are a source of robust voting rights protection — meaning state courts could have a crucial role to play."

"Virtually all state constitutions have a clause granting state citizens the fundamental right to vote. (Only Arizona’s does not, but its courts have construed its state constitution as still essentially conferring the right to vote.) About half of the state constitutions declare that elections must be 'free,' 'free and equal,' or 'free and open.' And a few state constitutions, such as Florida’s, even dictate rules that require fairness in redistricting," Douglas said.

Douglas's suggestion, in essence, is for people fighting gerrymandering to stop trying federal litigation and instead focus on invoking state constitutions and bringing challenges to state Supreme Courts.

Another option is a constitutional amendment. Dave Dodson made the case for a constitutional amendment by arguing that "nonpartisan efforts" at the state or federal level to target redistricting are almost always thinly veiled attempts to retain partisan power. For instance, former President Barack Obama recently backed All On The Line, a redistricting committee with the stated goal of "One Person. One Vote." But nine of their 10 targets to reform redistricting are states controlled by Republicans.

"Their efforts noticeably skip over America's most gerrymandered state, Maryland, which has systematically disenfranchised Republican voters," he wrote. "Six of the 10 most gerrymandered states, like West Virginia or Kentucky, are also not targets, for the obvious reason that fair redistricting for Republican dominated states would not yield additional congressional seats for Democrats."

Dodson's novel solution is to include an amendment that doesn't just protect partisan gerrymandering based on race, but also adds "political beliefs" to the protections currently afforded in the 15th amendment. That way, it'd be equally unconstitutional to gerrymander maps based on mined data to predict voter behavior as it is to draw maps based on racial makeup.

Others have also proposed a constitutional amendment that would mandate independent commissions or prohibit a certain level of creativity in drawing maps (say, by enforcing a certain standard of straight lines in redistricting boundaries). Some have made the case that a new amendment isn’t needed, because partisan gerrymandering violates the First Amendment. The case here is that states are always prohibited "from acting in ways that discriminate against speech expressing a disfavored point of view," even when they're exercising authority that has been granted to them.

Christopher and Linda Fowler have said the way Americans organize themselves makes it impossible to enforce fairly drawn single-member congressional districts. Because citizens have "clustered" in certain areas — specifically in cities — and live amongst like minded voters, the Fowlers suggest we need “multi-member districts.” That is, districts with higher populations and multiple members serving the same district.

"Even when district boundaries are drawn in reasonable ways, Democrats are concentrated in large, urban areas, while Republicans are spread across suburbs and rural areas," they write. "As a result, GOP candidates win with smaller margins -- wasting fewer votes -- and claim more seats than their share of the state vote would suggest."

Multi-member districts, they say, would make "packing" and "cracking" districts harder, create fewer districts (so fewer opportunities to manipulate via gerrymandering), and larger districts that would attract more coalition building and more competitive candidates across parties and ideologies. Their proposal would also include a move toward Ranked Choice Voting, which they say would give voters the flexibility to ensure their top preferences make it into office.

"In our forthcoming research on possible multi-member districts in Pennsylvania, we used a computer algorithm to repeatedly and randomly divide Pennsylvania into six congressional districts containing approximately 2.1 million people each, three times the size of the eighteen districts the state has now," they wrote. "In the tens of thousands of valid maps that resulted, each of these larger districts closely matched the state on key demographic categories, such as age, education, income levels, race, urban or rural. Most important, they also contained fewer lopsided partisan blocs, increasing the chance of competitive elections and reducing the number of wasted votes."

Another interesting proposal is the "define and combine" method. In this scenario, the majority party in a state legislature would still get to draw districts how it wants them based on recent census data and past district lines. But with a catch: It would have to draw twice as many districts as called for by the population, without creating any "donut districts" where one encapsulates another. Then, the minority party goes second, and gets to combine the sub districts in any combination they want, so long as they are being put together with a neighboring district.

The result, political scientists at Harvard and Boston University suggest, would be a process where both sides succumb to their partisan motivations but are limited in a way that would ensure a fairer and more representative process. By giving each party one move, the amount of packing and cracking is reduced.

While all this is going on, another fascinating development is also taking place: mathematicians are now joining the battle. The methods they're using are difficult to put into layman’s terms, but the upshot is that they are creating millions of potential maps to try to demonstrate the guardrails of what is obviously fair and what is obviously not — and then hoping those maps can both educate the public and be used in legal battles (or by independent commissions) to land in a way such that gerrymandering isn't disenfranchising millions of voters.

In essence, these mathematicians are responding to the sophistication of computer algorithms and congressional mapmaking with their own scientific responses, hoping to illustrate clearly where redistricting has gone wrong.

Of course, there are many other potential solutions out there, but these are a few of the most popular. Some have simply argued that the goal of resolving gerrymandering is a lost cause, so long as single-member districts and disproportionate representation exist in Congress.

My take.

If you want to truly understand how cynical politicians can be, the issue of gerrymandering is a good place to start. And few states are as emblematic as California.

Dan Morain, the former Sacramento Bee writer, has documented this in illustrative terms.

In 2010, current House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) was on the front lines of an effort to kill a new California independent redistricting commission. At the time, Pelosi was one of 17 current and former Democratic members of the House from California who donated money to try to stop the effort, describing it as a Republican power grab that would give unelected bureaucrats control over voters.

Meanwhile, Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), the current leader of Republicans in the House and a loyal Trumpist, celebrated the commission as a tool to keep elected officials more accountable and empower Black and Latino voters.

Reading that now might be shocking — or at least it should be — given that in 2022, Pelosi is leading the effort to pass a voting reform bill that would mandate independent commissions nationally and McCarthy is doing everything in his power to prevent that bill from becoming law.

What changed? Nothing about the argument. Just the results: Republicans prevailed in 2010, ushering in the California Citizens Redistricting Commission, which was made up of five Democrats, five Republicans and four voters with no party preference. But rather than empower Republicans as McCarthy, Pelosi and donors on both sides thought it would, the commission actually wrested power from them. In 2010, California Democrats held 34 seats and Republicans held 19. Today, Democrats hold 42 seats to Republicans’ 11. And magically, Pelosi now supports independent commissions and McCarthy opposes them.

The reason for this is simple: Republicans gerrymandered so successfully in 2010 that independent commissions nationally would almost certainly favor Democrats. So, Pelosi backs the proposal. McCarthy knows incumbents have the advantage when gerrymandering is allowed, so keeping independent commissions out benefits the Republicans who already have the upper hand. That's why he went from penning op-eds proposing independent commissions in 2005 to quotes like this in 2021: “It’s not designed to protect your vote. It’s designed to put a thumb on the scale of every election in America and keep the swamp swampy.”

That's not to say there is no just, fair, ethical or moral upper hand here. There is: partisan gerrymandering should be crushed in every way possible. It's just to say that, while Republicans have benefitted much more from partisan gerrymandering in today's climate, both Democrats and Republicans are guilty of using this tool to their advantage — and openly willing to change teams when it serves them.

In my view, the most deleterious impacts of gerrymandering are the limits it puts on minority voters and the impact it has on competitive districts.

While class and education are becoming the new compass used to measure political affiliations, race is still at the top of the food chain. And Black voters have been harmed most by partisan gerrymandering. They end up clustered into majority-minority districts, which on the surface could look like a good thing. In some ways, these districts have resulted in a more diverse Congress with more minority members. But the catch 22 is that it has also diluted the power of Black and minority voters by concentrating them so that their influence exists in fewer districts rather than across many.

Reducing competition is equally insidious. The fact that an overwhelming number of congressional races are not even remotely competitive does a few things: First, it allows — in fact, it encourages — candidates to be as partisan and out on the fringe as possible. This is because incumbents know that in order to win, they only have to turn out their base, which often fits the most extreme caricature of voters in that district.

Second, because the outcome of the race is predetermined, it discourages voters from participating. That is almost certainly a component of why turnout in U.S. elections is so low. "My vote doesn't matter" is a refrain a lot of Americans lean on, and in a lot of cases they're not wrong. Worse, their detachment only reinforces the entrenchment of the two-party system and the excessive partisanship we see among candidates.

Third, the success of gerrymandering further encourages the behavior from the parties in power. We just witnessed this play out in Ohio, where the GOP attempted a gerrymandering scheme so brazenly corrupt that the Republican-majority state supreme court actually shot it down. And that was after Ohio voters passed a constitutional amendment that would encourage more fairness in gerrymandering.

As for the 2022 midterms, Democrats have spent a lot of time focused on the prospect of Republicans gerrymandering their way to a congressional majority. But it's becoming apparent that the Republican advantage is mostly baked in already, thanks to their extraordinary success in 2010. Democrats’ biggest problem in 2022 won’t be partisan gerrymandering, but Joe Biden's approval ratings being underwater and the wave of Democratic incumbents planning to vacate their seats. If they’re interested in saving their majority, they’d be better served focusing their energy there.

Long-term, of course, we should all be demanding a fair solution. I'm just not exactly sure which one is the best.

If I had to rank them, I'd put multi-member districts at the top of my list. It is, to me, the most compelling and simple of all the ideas out there, and — critically — the one I could see gaining the most bipartisan traction. Independent commissions are a close second, but there are enough examples of commissions gone wrong (even if it is the minority of cases) that the attack ads write themselves. Fighting partisan gerrymandering at the state level, as Douglas suggested, is a noble cause. But it's a bandaid on a severed limb, and even if it were successful in a handful of states it would take years to stop the bleeding and ultimately seems destined to have a minimal impact nationally.

What is clear as day is that the system we have now is broken. When it comes to congressional races, it is not hyperbolic to say that we are no longer choosing our politicians — they are choosing us. It doesn’t matter whether you vote Republican, Democratic, or somewhere in between. This is an issue that is impacting you.

And if history is any indication, it'll take the will of the people leveraging the one tool we have — the democratic process, however damaged it may be — to reverse course.

You can share this post on Twitter by clicking here.

You can share this post via email by clicking here.

You can share this post on Facebook by clicking here.

You can share this post on LinkedIn by clicking here.