Plus, some really important reader feedback from yesterday.

I’m Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, ad-free, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum. You can read Tangle for free, and you can reach me anytime by replying to this email. If someone sent you this email, they’re asking you to subscribe. You can do that by clicking here.

Today’s read: 11 minutes.

I’ve unlocked this Friday edition for all readers. I’m breaking down the mail-in voting and voter fraud claims because there’s far too much confusion on these topics. Given the content, I encourage you to share this edition with friends, family and colleagues. There are also some quick hits on the news at the end. But first… some reader feedback.

U.S. Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class Zoe Thacker.

Reader feedback.

Yesterday, I answered a question from Eric in Mesa, Arizona, about why Tangle has seemed to “lean left” recently. In defending the newsletter, and my work, I wrote that “I am often accused of being too conservative or too liberal, almost exclusively based on when people sign up for the newsletter.” I also said that I frequently get hammered by both sides for being too this or too that, which to me usually demonstrates that I’m giving enough space to different viewpoints — which is the entire point of Tangle.

To illustrate this point, I thought it’d be valuable to share with my readers some responses to yesterday’s newsletter. I got dozens and dozens of emails, but these are just a few that — I think — make my point and represent the kinds of things I encounter on a daily basis. Because everyone, including me, has biases, those biases inform the way all of us consume and judge whether something like Tangle is biased. Here are a few emails I got yesterday to show what I mean:

Dylan wrote in and said, “I think a lot of the leftists who subscribe to this would laugh at the suggestion that you are one.”

David wrote in and said, “As much as I like you, and as much as I like the newsletter, I too have had the concern of the reader that maybe Tangle leans a little too far left.”

Konnie wrote in and said, “I can't believe someone would call you on ‘leaning left.’ With the mess that is the White House, all that is needed is to take an unbiased view of what's happening in the Trump administration to call it the disaster that it is.”

Jordan wrote in and said, “I'd also point out that on the issue about Israel-UAE you came out leaning further to right.”

Frank wrote in and said, “I agree with recent claims of your left-leaning tendency and encourage you to give that some thought as you craft each newsletter.”

Another David wrote in and said, “I think that it is also important to note that there is a significant majority that are left-leaning. I say this based on popular votes in past elections and polls that repeatedly have majorities in the 'left’ side of issues. So, 'center' is still 'left-leaning', wouldn't you say?”

Stefan wrote in and said, “As always, a great job and a good defense against critics calling you out for left-wing bias. As a British Conservative living in Hong Kong, I would never have recommended your newsletter to numerous friends if you were really guilty of peddling the woke mantra.”

Benjamin wrote in and said, “Big thanks for answering that last question! I agree with much of what you're saying and putting out, but I still think you lean a little more conservatively.”

Kerry wrote in and said, “I know you are transparent about your political views, but I fairly consistently see that influencing and even slanting your overall reporting [to the left].”

Nancy wrote in and said, “I'd like to unsubscribe from the free list. You are not a centrist.”

There are dozens more just like these (well, not the last one — that one was unique!) but I thought this was worth sharing to make my point. As always, I encourage you all to continue to offer this kind of feedback (except the last kind, don’t do that) — it forces me into introspection and it makes Tangle better.

The story.

Over the last couple of weeks, mail-in voting, voter fraud and the upcoming 2020 election have been the dominant topic of conversation in politics. But that conversation has been marred not just by misinformation, but also by what seems to me to be a general lack of understanding of how voting works in America and why the 2020 election is precarious.

Part of the issue is the politics of it. President Donald Trump has repeatedly claimed widespread voter fraud in America, rigged elections and — more recently — that mail-in voting is ripe for foul play. Democrats have responded by saying election fraud is non-existent or extremely rare, claiming the president is trying to sow confusion to lay the groundwork to contest the election once he loses.

Today, the United States Postal Service Postmaster General Louis DeJoy is also testifying before Congress. His testimony (which I discuss at the end of this newsletter) is critical to setting the stage for how the 2020 election will go down. But pundits across the spectrum have used cherry-picked arguments and misleading comments that are causing widespread confusion.

To address this confusion, I thought it’d be fun (and important) to lay out the arguments being made, the misunderstandings that are happening, and explain and define the general terms of what’s going on for Tangle readers. This edition is going to cover mail-in voting versus absentee voting, voter fraud versus election fraud, the underlying politics of this argument and the very real challenges and risks of what’s coming in November. When you’re done reading, you should be able to spot the B.S. and have a better grasp of the arguments.

Mail-in voting.

One of the greatest sources of confusion that I’ve noticed is that people seem to be discussing mail-in voting and absentee voting as if they are interchangeable or synonymous. Traditionally, they are not.

All absentee voting (also called absentee ballots) is mail-in voting. But not all mail-in voting is absentee voting. I’ll say that again: all absentee voting is mail-in voting, but all mail-in voting is not absentee voting.

Absentee voting has been around since the Civil War. It’s typically a way for someone to vote in an election when they are not able to physically be present at a polling place. For instance: college students, Americans living abroad, members of the military, or someone who is physically disabled. Over the years, absentee voting has become so popular that there is now “no-excuse absentee voting” in 34 states and Washington D.C. That means any voter in those states can request an absentee ballot, even if they are able to vote in person on election day, and then send their vote in via mail. In fact, President Trump votes by absentee in New York and Florida, as does his family, and they have for many years.

Over time, absentee voting has sort of adopted other names. People call it absentee ballots, mail balloting, vote by mail ballots, and some states even call it mail-in voting (which just makes everything more confusing).

Technically speaking, absentee voting is mail-in voting. You are casting a ballot by mail. But usually, when an election expert or politician refers to mail-in voting, they’re talking about any kind of vote by mail or “all-mail” elections. That happens in just five states: Utah, Washington, Oregon, Colorado and Hawaii. Every year, eligible voters are mailed ballots, then they fill out the ballots and return them by mail or self delivery. But, again, the language is confusing here: all-mail elections do not literally mean there is no in-person voting. There is. They just mean every citizen can vote by mail if they want.

In these elections, there are all sorts of checks to verify ballots. Voters have to sign their ballot and sign an affidavit. Some ballots have bar codes. Election workers compare signatures, addresses, voter rolls and files and make sure things line up. Mail-in voting almost always goes off without a hitch, and over the years these five states have had very little trouble performing fair and secure elections.

Recently, President Trump has clarified that his criticisms are about these kinds of elections. “Absentee ballots, by the way, are fine,” Trump said last week. “But the universal mail-ins that are just sent all over the place, where people can grab them and grab stacks of them, and sign them and do whatever you want, that’s the thing we’re against.”

In the midst of COVID-19 conditions, states have responded in two ways: some have dropped the requirements for absentee ballots, saying anyone can vote by absentee — which would mean they have to request a ballot to vote. Some counties have gone the all mail-in route, attempting to send out ballots to all registered voters even if they haven’t requested them. For instance, in New Jersey, Gov. Phil Murphy ordered the state to send ballots to all registered voters for the primary.

A little common sense would indicate that this could cause some problems. States are trying to do something they never have, in the middle of a pandemic, with slashed budgets and smaller workforces. Some issues have popped up already: When some unattended ballots were found in Paterson, New Jersey, it became a national story about the risk of inexperienced states trying to pull off a mail-in election — and actually led to election fraud charges.

Voter vs. election fraud.

Another source of confusion seems to be the debate over voter fraud and election fraud.

First, before getting into the frequency and risks, it’s again worth defining the terms here. Election fraud is about changing many votes at once. Think about the kind of stuff you see in the movies; serious organization, a vulnerability in the election process, vast conspiracies to change votes, hacking of election machines, or widespread stealing and stuffing of absentee ballots that are falsified and filled out.

Voter fraud is, comparatively, much less important because it’s far less impactful. Voter fraud is about one single voter casting a ballot in an election they are not allowed to be voting in. This could happen with somebody voting in a state they no longer live in because they’re still on the rolls, or voting as someone they aren’t, or voting illegally when they’re not registered, or voting once in one district and then driving somewhere else to vote again.

Like mail-in voting and absentee voting, voter fraud and election fraud are often used interchangeably despite the fact they are not the same thing in terms of scale.

In this case, though, the distinction is much more important. Election fraud is, generally speaking, extremely rare and very difficult to pull off. Republicans often warn about the threats of election fraud, but we have had very few instances of election fraud in America — especially in federal elections. In fact, in 2018, we had one of the biggest election fraud cases ever, and it was committed by a Republican candidate for Congress in North Carolina. Someone working for the Republican candidate Mark Harris had gone around North Carolina to “unlawfully collect, falsely witness, and otherwise tamper with absentee ballots.”

More recently, there have been two big cases of election fraud: In Philadelphia, a former Democratic judge of elections admitted to charges of voter fraud in May. His scheme was comically dumb: he literally stood inside a voting booth, stuffing ballots and voting as many times as he could as fast as he could “while the coast was clear.” Someone paid him to do it. There was also a case in New Jersey that has gotten a lot of attention which we’ll get to in a minute.

Voter fraud, the individual kind, appears to be slightly more common, and together there are certainly cases of voter fraud and election fraud to point to. The White House — to make its point — actually linked to a database of voter and election fraud cases across the U.S. The database lives on the political group Heritage’s website. At first glance, it may look damning: it cites 1,296 cases of confirmed voter and election fraud. But if you click through the database, you’ll notice those 1,296 cases span decades, and include all 50 states.

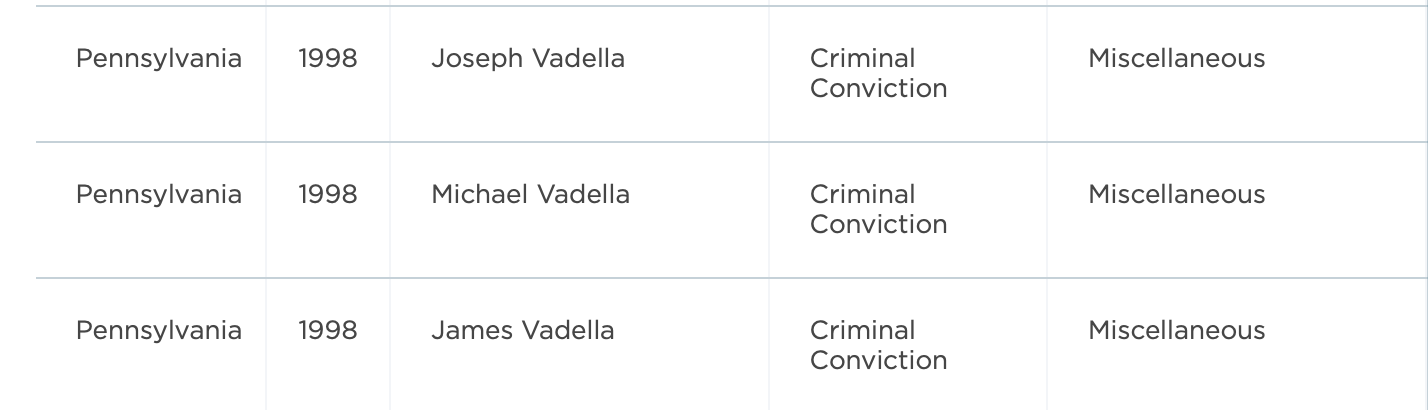

For instance, I looked at my home state of Pennsylvania and found the database cited cases going all the way back to 1998. In fact, the database counted three instances of election fraud from one election fraud incident where a family falsified absentee ballots to help their brother win a small, local election in 1998:

Speaking of Pennsylvania, the struggle to identify moments of serious election fraud was actually on display in court there recently. The Trump administration has sued Pennsylvania’s Secretary of the Commonwealth Kathy Boockvar to prevent her and the state’s election boards from placing secure drop boxes around the state for people’s mail-in ballot returns. The Trump campaign alleged in its court filing that the drop box system “provides fraudsters an easy opportunity to engage in ballot harvesting, manipulate or destroy ballots, manufacture duplicitous votes, and sow chaos.”

In responding to the claim, the defendants in the case asked the Trump administration to provide evidence of the existence of voter fraud, arguing the campaign’s lawsuit was “replete with salacious allegations and dire warnings” about the election in Pennsylvania and that they must provide evidence for their allegations that fraud is a threat. The judge granted the motion, ordering the campaign to provide the evidence. But they couldn’t.

In a 524-page document, some of the cases from the Heritage website are actually used — including an election judge who altered vote totals between 2014 and 2016 while working for a political consultant. There was also an example of poll workers harassing voters in 2017. But there were no examples of mail-in voting fraud in the discovery document.

This, again, is not unlike the last time Trump made a crusade against election and voter fraud. In 2016, after winning the election but losing the popular vote by nearly three million votes, the president repeatedly claimed that he lost the popular vote because of voter fraud and illegal immigrants voting. Trump launched a commission on voter fraud with taxpayer money to prove his claims (something he still claims today). But the commission disbanded after Republicans in states across the U.S. refused to cooperate, citing no evidence of widespread fraud in their own elections. Maine’s Secretary of State Matthew Dunlap, one of 11 members of the committee formed by Trump, called it “the most bizarre thing I’ve ever been a part of.”

Making sense of it.

Voter fraud happens. Election fraud happens. Any claims that voter fraud or election fraud are totally nonexistent are not true, but what is true is that it can accurately be described as extremely rare. Heritage’s own data bears this out: there are dozens of elections in every state in any given year. 1,296 cases of voter fraud across all 50 states with some records going back decades would indicate that very, very few elections ever have voter fraud or election fraud issues. Given how hard it is to pull it off, and how elections are often audited after the fact, it’s safe to assume that these 1,296 cases encompass almost all of the election and voter fraud that’s been committed in the last few decades.

Republican claims that voter fraud or election fraud are a huge threat to our elections are exaggerated, though there are plenty of reasons to be on high alert. In New Jersey, a judge just ordered a new election after postal workers discovered hundreds of ballots bundled together in the mail. The workers’ suspicions set off an investigation that led to two elected leaders being charged with voter fraud. But, again, the case actually illustrated how hard it is to get away with fraud in an election. It was a little-watched local council race and it was still easy to detect.

In reality, the New Jersey case actually showed other challenges of voting by mail: thousands of ballots were thrown out because they were filled out incorrectly or disqualified because the signatures didn’t match those on file, not because they were part of the fraud (many news outlets erroneously reported it that way). It’s a reminder that if you’re not voting in person, you have to be extra diligent about filling out your ballot.

There’s another element to all of this, too: the political ends of election fraud being real. A lot of elected Republicans are actually frustrated by Trump railing against mail-in voting, and they’ve said so publicly. They understand that many of their voters do and want to vote by mail in 2020, too.

At the same time, it is generally a Republican talking point to institute voter ID laws. This is not a big secret and not some liberal narrative — Republicans call for voter ID laws across the country during almost every election cycle. The existence of voter fraud is an anchor for those calls, and without voter fraud, there is very little reason to force voters to have identification.

There are obvious, logical reasons to have voters show identification before they vote. You want proof the person is who they say they are and has only voted once. But there are less obvious reasons not to have voter identification. Even without IDs, it’s very hard to vote as someone you aren’t (there are lots of layers of checks on who is voting). 21 million Americans who are of voting age don’t have government identification (yes, 21 million). Voter ID laws would almost certainly hurt minority, poor and younger voters the most, but several studies have actually struggled to determine whether the laws would benefit Republicans more than Democrats (which is the common refrain from the left).

When it comes to voter fraud, though, there’s very little reason for identification. Every reputable study that I can find has shown the same thing: voter impersonation is almost unheard of. One well-regarded study found attempted voter impersonation happens in “one out of every 15 million prospective voters.”

The real risk in 2020.

One of the most recent claims related to the risk of 2020 came from Michigan. President Trump and some of his allies in the media have been pushing a story about how more than 800 votes from dead people were mailed into the primary election there a few weeks ago. Donald Trump Jr. shared a tweet about this case, and used it to illustrate his claims that something nefarious was happening and these voters were not legit.

But the reality is far more boring, and actually illustrative (again) of something else entirely. The 846 ballots that got rejected were rejected because the people died between the time they cast their ballots and when the election happened. In other words, this was not fraud. This was not an example of people voting under the names of people who had died. Voters mailed in their ballots, died shortly after their ballots were sent in, and then had their ballots rejected because they died before the day of the in-person election (yes, that is an interesting voting law for you!)

This happens in Michigan every year, the Secretary of State said. And it shows just how cynical some people claiming threats of election fraud are. Trump Jr. did not correct his statement or follow up about it, and rejected interview requests about his claims that the dead voters being rejected was proof of something shady. On the contrary, the rejections illustrated how well the system works and how closely people are tracking this stuff. The idea that these dead voters were actually identified and parsed out in the middle of the pandemic chaos is proof of how well the system is working, not proof of it being broken.

Which brings me to the real risk of 2020.

None of this is to say that the upcoming election will go off smoothly or be simple. Your average presidential election has challenged ballots, voters purged from rolls, votes lost in the mail, signatures that don’t match, dead voters whose votes need to be rejected, contested vote counts, and all sorts of other complicated wrinkles.

This election is going to be even more difficult to follow. In all likelihood, millions of votes won’t be counted until days after election day. Many of those ballots will have issues that are cause for them to be thrown out: they’ll be sent in late, have mismatching signatures or be filled out incorrectly. Some, perhaps, will be duplicates or part of some kind of voting fraud or election scheme (though, again, that seems very unlikely). Many thousands will come from voters who die before election day — like the cases in Michigan — and will need to be thrown out.

But we’re perfectly capable of handling it. Roughly one in every four Americans voted by mail in the last two federal elections. In 2018, 31 million Americans voted by mail in the midterms — 25.8% of all the votes cast. And we have plenty of effective systems to try to replicate: Oregon has pioneered mail-in voting, as the Brennan Center pointed out. More than 100 million mail-in ballots have been cast since 2000 there, and there have been about a dozen cases of fraud (that’s a .00001% rate). “It is still more likely for an American to be struck by lightning than to commit mail voting fraud,” the Brennan Center noted.

Almost all states have the tools to do mail-in elections properly. Voters need to identify themselves on ballots and via the envelopes they mail in with birthdays, addresses, the last four digits of social security numbers, and signature matches. Many elections have barcodes on ballots, which could still be widely adopted in time for November. Secure drop off locations would help, although — considering the Trump administration’s lawsuit in Pennsylvania — it seems the president is hellbent on trying to slow those rollouts from happening.

And, of course, there are the harsh penalties for voter fraud, which should be well advertised in every state. The civil and criminal penalties for voter fraud are up to five years in prison and $10,000 in fines. We should make sure that’s known to voters so anyone who is so desperate to see a Trump or Biden win will think twice about trying anything funny. Finally, there’s the post-election audit, which will require our patience.

Embracing these policies and resources will help 2020 go off without too much chaos. Voting early, voting in person if you can, and sending in your vote as soon as you feel comfortable making your decision will all help, too. But one thing is certain: if the country can work together these next couple of months to embrace all forms of voting and the systems that protect those votes, we can have a fairly normal — if slightly delayed and chaotic — election in 2020.

Enjoyed this?

Typically, Friday editions are for subscribers only. But I was inspired by The Wall Street Journal, which recently dropped its paywall on important state voting options in the 2020 election. If you enjoyed this, and want more content like it, this is the kind of thing Tangle subscribers regularly get on Fridays. You can subscribe by clicking here.

Quick hits.

- Joe Biden accepted Democratic nomination for president last night and delivered what was the most highly-anticipated speech of his campaign. His delivery received some positive reviews across the political spectrum, including from Fox News. Bret Baier said it was the best he’d seen Biden on the stump and Chris Wallace said Biden “blew a hole” in Trump’s narrative about his abilities, perhaps the best outcome the Biden campaign could have hoped for. President Trump responded to the speech on Twitter: “In 47 years, Joe did none of the things of which he now speaks. He will never change, just words!”

- Postmaster General Louis DeJoy is testifying in front of Congress this morning and has made big news already. He committed to processing election mail as first class mail regardless of the postage used, which would accelerate its speed to polling places significantly. He also pledged the postal service will prioritize ballots the week leading up to election day and said he planned to vote by mail himself.

- A federal judge dismissed a lawsuit from President Trump aimed at blocking a subpoena for his financial records. The Supreme Court ruled last month that presidents are not immune from investigation and denied Trump’s effort to protect his financial records, but sent the lawsuit back down to the lower courts where Trump’s team could keep fighting. Trump’s lawyers are expected to appeal the ruling, and many observers think the legal team is hoping to run the clock until after the 2020 election.

- Andrew Yang re-appeared in the spotlight last night, delivering a brief address at the DNC convention that targeted disaffected voters from 2016. “I get it if you voted for Trump or didn’t vote at all back in 2016, I get it,” he said. “But we must give this country, our country, a chance to recover… and recovery is only possible with a change of leadership.” Yang is an interesting example of an under-the-radar candidate who had appeal amongst many swing voters (and even some Trump voters) during the Democratic primary, and his appeal to the #YangGang to come out for Joe Biden got homepage coverage from Politico.

- Facebook says it is bracing for post-election chaos with a “kill switch” that would turn off all political spending if the election is contested. Employees at Facebook are “laying out contingency plans and walking through post election scenarios that include attempts by Mr. Trump or his campaign to use the platform to delegitimize the results,” The New York Times reports. If Trump falsely claims on the site that he won another four-year term, Facebook is putting in place measures that will allow it to minimize Trump’s reach on the platform.